Fibromyalgia and arthritis

Introduction

Fibromyalgia and arthritis are common musculoskeletal conditions causing chronic pain (7.1)1. A survey of 99 general practitioners in Italy showed that 32% of all visits were for pain, with 47% for acute and 53% for chronic pain2. In this survey, joint-related pain comprised the most common individual diagnostic category (23%).

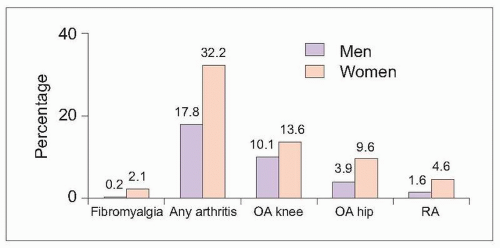

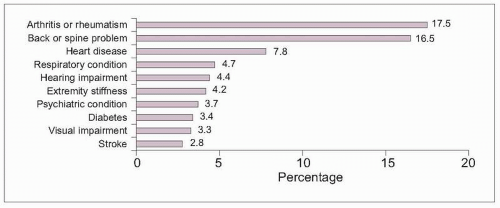

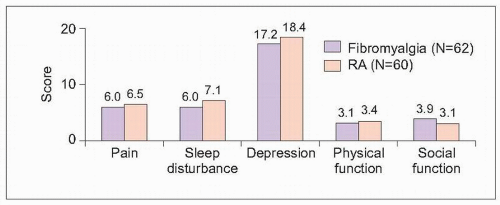

Chronic rheumatologic conditions are a major cause of disability3. Of all medical problems resulting in a disability, arthritic conditions are the most common (7.2). Almost 18% of adults with a disability attribute their disability to arthritis or rheumatism. Interestingly, despite lack of joint damage in fibromyalgia, disease impact is similar for patients with fibromyalgia or rheumatoid arthritis (7.3)4.

7.1 Prevalence of fibromyalgia and arthritis. The prevalence of self-reported fibromyalgia and arthritis was determined for a Dutch population-based sample. Both fibromyalgia and arthritis were more common in women. OA: osteoarthritis; RA: rheumatoid arthritis. (Based on Picavet HJ, Hazes JW, 20031.) |

7.2 Health conditions resulting in disability in the United States. Using surveillance data, the Centers for Disease Control reported that 22% of adults in the United States have a disability, defined as having a functional limitation, restrictions for work, use of an assistive device, or receipt of federal disability benefits. The most commonly reported health conditions resulting in disability are arthritis or rheumatism, followed by back or spine problems, each affecting slightly less than one in five persons with a disability. (Based on CDC, 20013.) |

7.3 Impact of fibromyalgia and arthritis. Symptoms and quality of life were compared in female outpatients in Istanbul with fibromyalgia or rheumatoid arthritis. Pain and sleep disturbance were measured using a visual analogue scale (0=none; 10=severe). Depression was measured using the Beck Depression Inventory, with a score >17 indicating depression. Quality of life was measured with the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale II subscales, with scores ranging from 0 (best) to 10 (worst). Symptom severity, depression, and quality of life were similar for patients with either condition. (Based on Ofluoglu D, et al., 20054.) |

Fibromyalgia

Case presentation

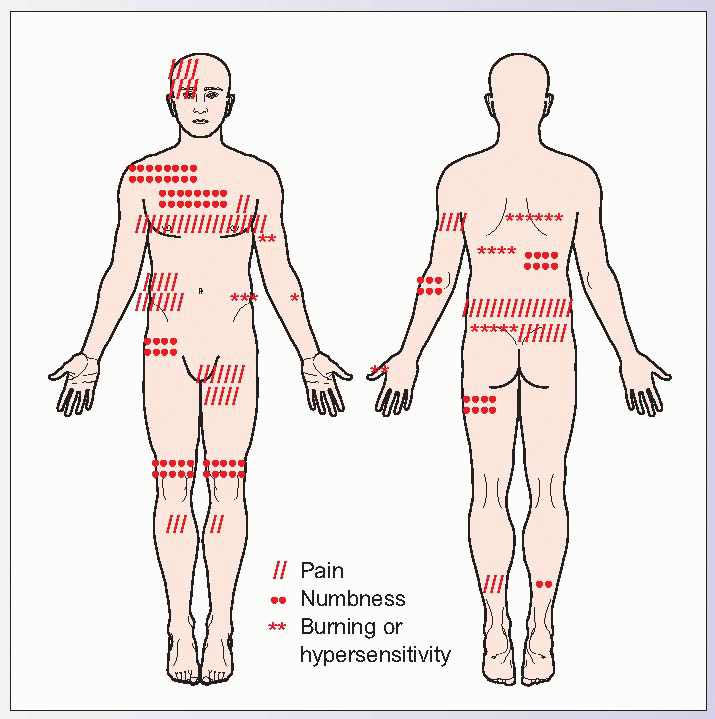

A 43-year-old corporate attorney complains of a 4-year history of diffuse pain. She began having back pain without any obvious trauma and progressively developed pain in her shoulders, chest, and legs over the next 6-8 months. Pain intensity would fluctuate among the pain areas on different days. Radiologic testing was unremarkable. She also reported extreme fatigue, difficulty concentrating, migraine headaches, anxiety, bowel irregularities, and frequent urination. Her complaints resulted in impaired work performance and she was asked to reduce her commitment to part-time. Her physical examination shows her to be bright and articulate, with good muscle strength and joint motion. At this point, she has had numerous, unremarkable blood tests and imaging studies and spends several days each week visiting doctors or attending different therapy appointments. Her frustration is evident when she verbalizes, “Every doctor tells me how great I look and that my physical examination is perfect. I know people think I must be exaggerating.” Her pain diagram is shown.

Fibromyalgia is recognized as a condition resulting in both chronic, widespread pain and a variety of somatic complaints. Like this patient, fibromyalgia patients typically have unremarkable musculoskeletal and neurological examinations, with normal laboratory and radiographic tests. Despite normal function for bedside testing, disability and psychological impairment are often substantial in fibromyalgia patients.

|

Epidemiology of fibromyalgia

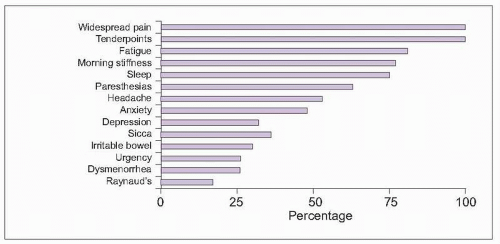

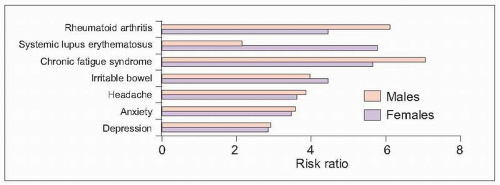

Fibromyalgia is defined as diffuse, chronic pain associated with tender body areas and somatic complaints (Table 7.1). Most patients with fibromyalgia experience a wide variety of fluctuating symptoms in addition to body pain (7.4)5. Fibromyalgia patients are also more likely to be experience a number of other rheumatologic, medical, and psychological conditions, contributing to the burden of this condition (7.5).

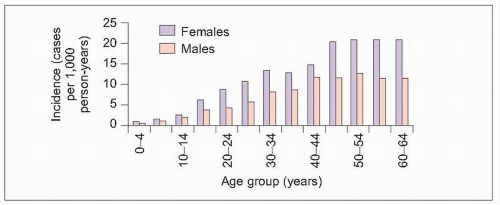

Fibromyalgia affects 2% of adults, predominantly women (7.6). Incidence rate increases with age for both genders, with women more likely to be affected throughout their lifetimes6.

7.5 Comorbid conditions and fibromyalgia. Using a large insurance claims database in the United States, the prevalence of concomitant illnesses was compared between patients with and without fibromyalgia. Risk ratios >1 were used to identify illnesses occurring with greater than expected prevalence (comorbid) among fibromyalgia patients. All of the conditions in the graph were comorbid with fibromyalgia, except for lupus in men, which failed to achieve statistical significance due to wide data variability (95% confidence interval=0.29-15.74). (Based on Weir PT, et al., 20066.) |

7.6 Epidemiology of fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia incidence rate was calculated using 1997-2002 data from a large insurance claims database serving about 62,000 members annually. Fibromyalgia incidence peaked at about 13 cases per 1,000 person-years for males and 21 cases per 1,000 person-years for females. (Based on Weir PT, et al., 20066.) |

Table 7.1 Diagnosis of fibromyalgia | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

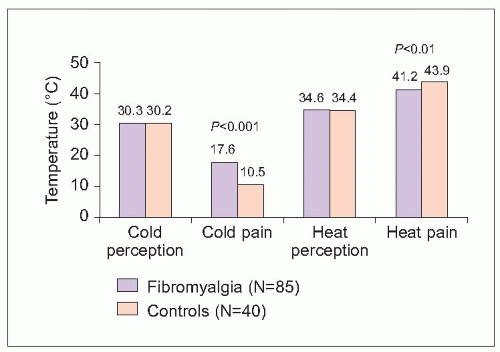

As highlighted by the case presentation, fibromyalgia patients typically have unremarkable examinations. Despite lack of physical or laboratory abnormalities, research studies show that fibromyalgia patients experience a variety of changes in the nervous system that result in increased pain sensitivity. In comparison to healthy controls, fibromyalgia patients experience a lower pain threshold, increased sensitivity to painful stimuli (hyperalgesia) and simple touch (allodynia), enhanced temporal summation, and prolonged after sensations7,8. These studies show that the nervous system is activated to produce a stronger response to pain than in nonfibromyalgia persons (7.7)9.

7.7 Enhanced perception of hot and cold pain. Quantitative sensory testing was performed at nonpain locations in fibromyalgia patients and healthy, matched controls. Nonpain perception thresholds were similar between groups, with nearly equivalent cold and hot temperatures required to result in perception of cold or heat. Fibromyalgia patients, however, reported experiencing unpleasant pain with cold and heat stimuli before controls, i.e. fibromyalgia patients reported a pain response before cold stimulation reached the same low temperature required to produce a pain signal in controls and before the heat temperature was as hot as needed to produce a hot pain signal in controls. Therefore, fibromyalgia patients experienced significantly lower thresholds for pain response to both cold and heat stimuli. Tolerance to cold pain was severely reduced by 66%. (Based on Desmeules JA, et al., 20039.) |

Assessment of fibromyalgia

Diffuse pain may occur with a plethora of medical conditions (Table 7.2). Patients presenting with generalized pain complaints require a careful history and examination to ensure the absence of potentially correctable or treatable medical conditions.

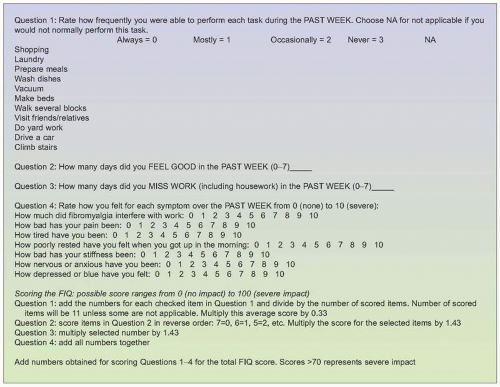

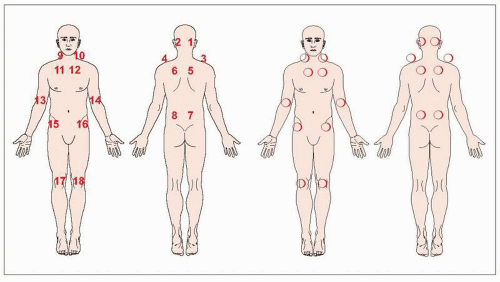

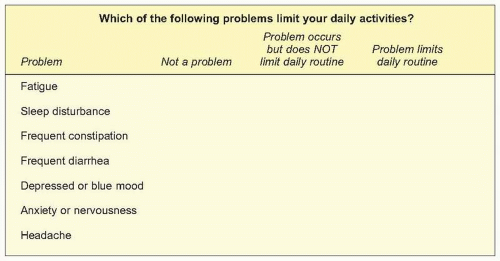

The diagnosis of fibromyalgia requires documentation of widespread pain and 11 of 18 painful tenderpoints, using a standardized tenderpoint examination (7.8). Documentation of the number and pain severity of tenderpoints can provide a tool to monitor progress with treatment at follow-up visits. Disability may be monitored using the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (7.9)11. In addition, treatment selection depends on identifying those symptoms typically most responsive to symptomatic improvement (7.10). Identifying disabling symptoms helps to clarify the most important treatment targets.

Table 7.2 Common causes of generalized pain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

7.8 Fibromyalgia tenderpoint examination. Test each labelled spot by exerting 4 kg of pressure with the thumb (watch for the nail bed to blanch). Record pain severity at each spot in the circles from 0 (none) to 10 (excruciating). Determine the tenderpoint count (number of painful tenderpoints scored >0) and tenderpoint severity (sum of all recorded scores). (Based on Marcus DA, 200510.) |

7.10 Assessment of disabling symptoms. (Based on Marcus DA, 200510.) |

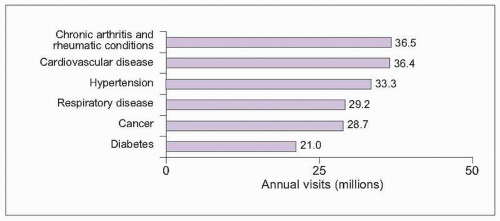

Arthritis

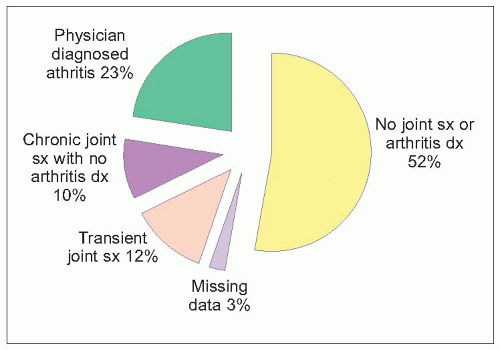

Arthritis or chronic joint pain, aching, stiffness, or swelling affects 1 in 3 adults (7.11)12. Chronic arthritis is a major cause of outpatient visits. Using data from two large, national surveys in the United States, arthritis or other rheumatic conditions were the primary diagnosis for 44 million of the total 959 million annual ambulatory care visits (7.12)13. The rate of arthritis visits increased with age, and women accounted for almost twice as many arthritis visits as men. Most arthritis visits were made to primary care health providers (53%), with only 16% made to rheumatologists. The most common individual arthritic conditions were osteoarthritis (OA) (20%) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (11%).

7.11 Prevalence of joint pain. A total of 212,510 adults ≥18 years old were questioned about joint pain, aching, stiffness, or swelling in a national survey in the United States and its territories (dx: diagnosis; sx: symptoms). (Based on Feinglass J, et al., 200512.) |

7.12 Reasons for ambulatory care visits. Number of ambulatory care visits was determined for different primary diagnoses, using data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey/National Hospital Medical Care Survey in 1997. (Based on Hootman JM, et al., 200213.) |

Osteoarthritis

Case presentation

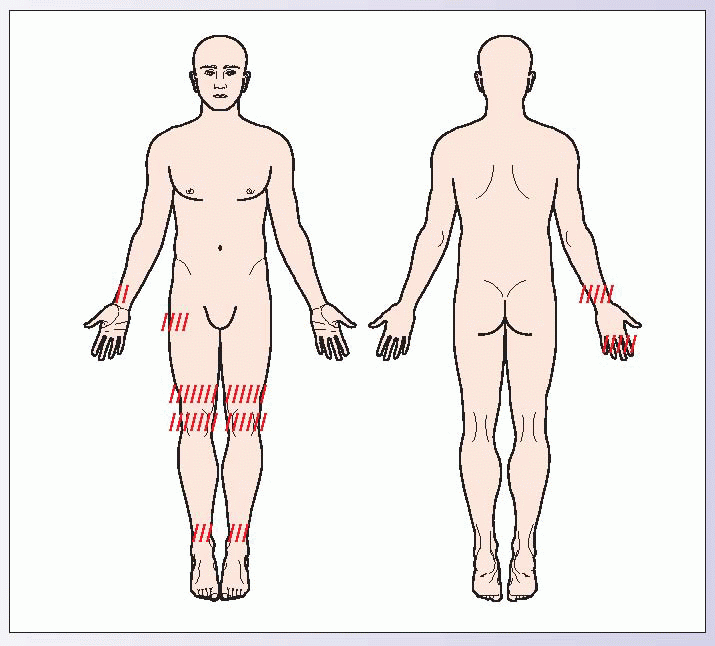

An overweight, 54-year-old hotel maid reports pain in her right hand, right hip, both knees, and both ankles for the last 8 months. “All of my joints are so stiff when I first wake up in the morning. After I’ve moved around for about 20 minutes, they begin to move better.” She has been able to continue her work, although occasionally her joints seem to lock and she is also very stiff for about 15-20 minutes after her lunch break. “My knees creak and groan like I’m an old lady whenever I walk.” Resting in the evening helps relieve her pain. Her pain drawing is shown.

Asymmetric pain of weight-bearing joints is characteristic of OA. Joint stress from excess weight and physical labour can aggravate degenerative arthritis. Patients typically report brief periods of morning stiffness that improve with using the joints. Pain often improves with rest. Joint crepitus and locking are characteristic of OA.

|

Epidemiology of osteoarthritis

OA is characterized by morning joint stiffness, bony enlargement, and pain with activities that improves with rest (Table 7.3). Nonjoint symptoms may occur from associated muscle spasm, nerve root impingement, or spinal canal stenosis. Systemic symptoms are not expected.

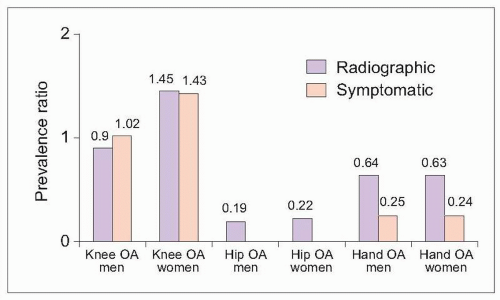

As adults age, the prevalence of OA increases. Hand OA occurs in about 10-30% of young adults and about 75% of adults 60-70 years old14. Knee OA is less common, but still affects 1 in 3 adults ≥75 years old. As the worldwide population ages, the impact of OA on society and clinical practices is expected to increase. Advancing age, female gender, obesity, and frequent joint stress from occupation or other activities may all increase risk for developing symptomatic OA.

Assessment of osteoarthritis

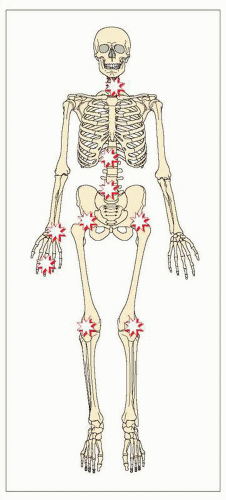

The diagnosis of possible OA requires identification of characteristic joint involvement patterns, physical examination findings, and radiographic abnormalities. OA typically affects high-use, weight-bearing joints in an asymmetric pattern (7.14). Characteristic physical examination findings are depicted in Figure 7.15.

Table 7.3 Diagnostic features of OA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

7.13 Age-standardized OA prevalence ratio Chinese:US Caucasians. Prevalence of OA in community-dwellers 60 years and older was compared in samples of Chinese adults in Beijing and Caucasian adults in the United States in three studies. Diagnosis was made based on radiographic evaluations and/or symptom reports. After adjusting for differences in age, prevalence ratios were calculated to describe OA occurrence in Chinese compared with Caucasian adults. Ratios for all three studies are depicted in the graph. Ratios >1 describe a higher prevalence in Chinese. Only female knee OA (diagnosed by either clinical symptoms or radiographic appearance) occurred more commonly in Chinese participants. Hip and hand OA were less prevalent in Chinese adults. Researchers in Thailand linked the increased prevalence of knee OA in Asians with habitual use of stressful knee positions, including squatting, lotus position, and side-knee bending18. (Based on Zhang Y, et al., 200115, 200317; Nevitt MC, et al., 200216.) |

7.14 Typical patterns of joint involvement in OA. Stars denote typical joints involved in OA, which characteristically affects overused and large weight-bearing joints. Joint involvement is often asymmetrical.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|