Key Clinical Questions

What are the most common causes of fever and rash in the hospitalized patient?

What is the pathophysiology of fever and rash?

What other clinical symptoms and findings are associated with fever and rash?

How can laboratory tests help with diagnosis of the etiology of rash?

A 25-year-old graduate student who living in student housing presented to the hospital complaining of a 4-day history of upper respiratory tract symptoms that have progressed to include fever and rash on his extremities. The rash began on his hands and feet as a pink, flat rash, but has progressed over the last several hours to be purplish in nature, and extends now to his trunk and face. He is admitted to your service for further evaluation and treatment. The rapid progression of the patient’s rash and the appearance of macular rash that progressed to petechiae and purpura raised immediate concern for meningococcemia. The patient was placed in droplet precautions, blood cultures were collected, and ceftriaxone therapy initiated. Vital signs revealed blood pressure of 110/60, pulse 118, respiratory rate 24, and temperature of 39.2. No nuchal rigidity was noted. The patient’s respiratory status declined and he was admitted to the ICU and intubated. Blood cultures grew Neisseria meningitidis at 24 hours and laboratory findings were consistent with DIC. A lumbar puncture was not performed due to severe thrombocytopenia. Multisystem organ failure developed rapidly. In addition to inotropic support, the use of recombinant activated protein C was considered. |

Introduction

The combination of fever and rash in the hospitalized patient has many different possible etiologies and the presentation can be varied, but an organized approach to the problem will alleviate some of the guesswork involved in diagnosing and treating these patients. This chapter will cover the presentation of rash plus fever and avoid a discussion of the causes of rash that are not typically associated with fever.

The clinical presentation of patients with rash and fever when they come to the hospital must be divided into categories of those who are critically ill vs. those who are not. Critically ill patients with rash often have fulminant onset of both the fever and the rash and must be diagnosed quickly to receive appropriate care. The timing of the rash is important for judging the severity of the disease with rapid onset often portending a more rapidly progressive course. The most worrisome cause of fulminant onset of rash is septicemia, especially purpura fulminans of meningococcemia, which can progress over hours or even minutes. More gradual or waxing and waning rash and fever suggest a more chronic process or one that may be noninfectious such as rheumatological disease or even a malignancy.

|

Approach to Fever and Rash at the Bedside

Some acute rash and fever syndromes are caused by infectious diseases that can be spread by airborne or respiratory droplets. Therefore, before beginning the history and physical, if such a transmissible disease is suggested, appropriate precautions should be instituted (Figure 86-1).

|

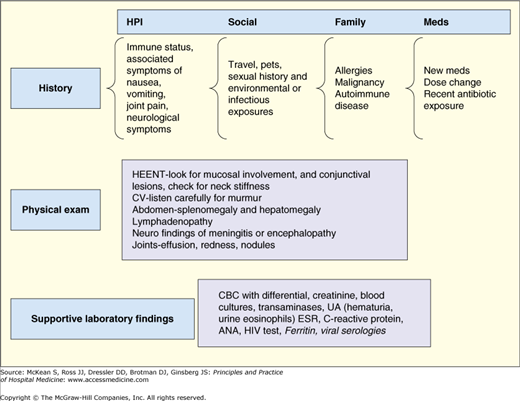

The age of the patient and the season of the year provide important epidemiologic clues to the differential diagnosis. Appropriate medical history that includes timing of the rash and fever and associated symptoms are important aspects of the initial evaluation. Specifically, patients should be asked about location of onset and timing of progression. Secondary changes to the rash such as those that might have occurred through self-treatments (lotions, over-the-counter ointments) or through excoriations or picking should be specifically asked about. In cases in which multiple lesions are present, in order to get a sense of how the rash has progressed, it may be helpful to ask the patient, “Can you show me an area that looks like how the rash started?” or “Are there any new lesions?” Associated symptoms of fever, sore throat, lymphadenopathy, and other systemic symptoms such as weight loss and joint pain should also be noted. Additionally, there are key aspects of each part of the history that should be explored. Medication lists should be scrutinized for new medications or changes in dosing of old medications. While many allergic reactions occur within the first several days or weeks of an exposure to a new drug, some reactions do not occur until after more prolonged exposure; in particular, antiepileptic drugs such as phenytoin are notorious for presenting with fever and rash after a few weeks of exposure, and only rarely within the first few days. Family and personal history of fever syndromes or allergies can also be a clue to the risk of drug allergy. Although often overlooked in adult patients, vaccination history and prior history of illnesses of childhood are important when evaluating some fever and rash presentations. Family history of rheumatologic diseases should also be specifically gathered, including history of lupus, vasculitis, or juvenile onset arthritis. Social, travel, and exposure histories are especially important when evaluating patients with fever and rash. Sexual history might suggest risk factors for acute HIV infection, syphilis, or gonococcal disease. Travel to endemic areas may suggest exposures to certain mosquito-borne illnesses such as dengue or malaria or tick-borne illnesses such as Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) or Lyme disease. Social history should include exposures to small children either through work (daycare, school teacher), or home.

As with all hospitalized patients, vitals signs and general appearance will contribute to the overall gestalt of the patient’s condition and may suggest rapid intervention or therapy. In particular, pulse-temperature dissociation (elevated temperature without elevation in pulse) may be a clue to infection with an intracellular pathogen, including Rickettsial disease, and is often present with drug reactions. Careful evaluation of lymphadenopathy and tenderness should be noted. Localized, tender lymph nodes may point to infectious etiologies while more diffuse lymphadenopathy is more commonly associated with a disseminated viral infection such as EBV, or malignancy, especially lymphoma.

Mucosal involvement of rash or ulcers, including oral and genital membranes should be noted. Cardiac exam should include careful evaluation for a new murmur or evidence of congestive heart failure, which could point to endocarditis. Abdominal exam should include palpation for hepatosplenomegaly, which can be found in noninfectious causes of fever and rash or in viral illnesses such as EBV or CMV infection. Splenomegaly is also present in many patients with subacute bacterial endocarditis. Careful joint examination, noting effusions, tenderness, or signs of synovitis as well as assessment for neurological symptoms should be done. The rash itself should be characterized by the color and type of lesion (nodule, macule, or pustule); distribution of lesions (trunk, head, etc); palpation and associated findings such as scale, purulence, or secondary changes.