CHAPTER 2

Family and Culture Within the Context of Primary Care

Carol Green-Hernandez, PhD, ARNP, FNP-BC, FNS • Stephen Paul Holzemer, PhD, RN

THE FAMILY–CULTURE RELATIONSHIP

THE FAMILY–CULTURE RELATIONSHIP

This chapter will illuminate the challenge to primary care providers to practice in a manner that is both family centered and culturally competent. Family and culture are concepts that are discussed separately, with the understanding that they are intrinsically related. The concerns of limiting bias when caring for others, the role of the patient in defining the conceptual significance of both family and culture in his or her life, and methods to assess this meaning will be examined.

Primary care that acknowledges the uniqueness of all participants is more likely to be successful in achieving positive outcomes (Hickey & Brosnan, 2012; Malloch & Porter-O’Grady, 2010). Although the provider is competent in health care content, including protocols that ensure safe care practice, the health consumer is the expert in knowing personal needs. Both provider and patient bring their own unique set of core beliefs, languages, and behavioral patterns to the health care experience. Thus, the provider must work toward the establishment of a common ground and respond to the patient–family with concern and respect (deChesnay & Anderson, 2008; Donohue-Porter, 2014; Hickey & Brosnan, 2012).

EMERGING FAMILY STRUCTURES

EMERGING FAMILY STRUCTURES

The emerging family of the 21st century is no longer defined exclusively by blood relation or marriage. Adults bond for multiple reasons with or without legal protection and responsibility. Patients define the concept of family for themselves. A group of women may come together with a religious conviction, and consider themselves a family (Buddhist or Catholic nuns). Women and men may legally bond in same- or opposite-gender relationships via marriage or domestic partnerships. Two people may become a family out of the need for mutual support in old age. Some people isolate from others and may choose not to engage in a family structure. In all of these unions, sexual interest and childrearing may or may not be a part of the family makeup.

PROVIDER AND PATIENT BIAS

PROVIDER AND PATIENT BIAS

The idea of family and culture may have different meanings for the patient versus the provider. A key to forming a successful patient–provider relationship is the recognition of personal beliefs and values and how they are congruent with or differ from those of the patient (and family). Patients living in multigenerational families may experience conflicts differently from those who live at a geographic distance from their family and friends. The provider and patient need to make every effort to learn about each other in ways that accept uniqueness and attempt to eliminate bias.

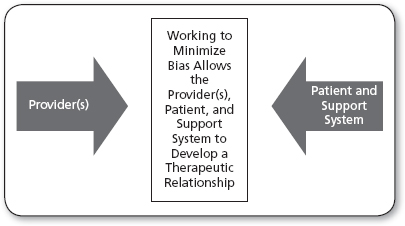

Bias refers to preconceived thoughts or judgments that are present in both providers and patients (and their support systems) that may interfere with the development of a therapeutic relationship. Bias is associated with personal or professional attributes like age, race, gender, level of education, sexual orientation, and country of origin. Bias is natural, may be protective, and cannot be eliminated. However, minimizing bias can help create health care interactions that are limited in behaviors that reflect agism, racism, sexism, ignorance-affluence, heterophobia, and ethnic hostility.

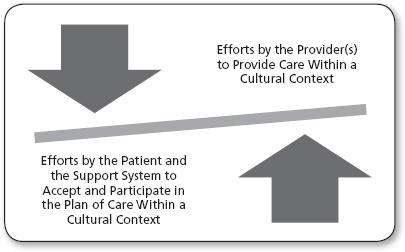

Patients and providers need to move beyond the differences of others, to develop a healthy interpersonal relationship. Figure 2.1 suggests that bias is anticipated between the provider and the patient. Figure 2.2 reveals that a balance to minimize bias is possible within the therapeutic relationship. Multicultural practice is driven by the provider’s ability to communicate objectively with a focus on those issues of commonality between and among all human beings. This means of communication is formulated on an awareness of commonalities as well as differences in cultural practices, ethnic and racial identities, and demographic variables. Ideally, this approach to communication recognizes both personal (provider) and patient biases, and of course health beliefs (Epner & Baile, 2012; Goodman, 2010).

Because the biases in care of patients may arise from family structures that are new or foreign to the provider, an emphasis on how the family functions may be a less problematic approach. The provider focuses on how the family functions, by exploring the following (and other) questions:

What are the agreed-upon goals for the patient?

What are the agreed-upon goals for the patient?

What roles will family, friends, and at times strangers play in supporting the plan of care?

What roles will family, friends, and at times strangers play in supporting the plan of care?

What policies and procedures are in place to deal with the legal concerns of releasing health-related information, and including others in the plan of care?

What policies and procedures are in place to deal with the legal concerns of releasing health-related information, and including others in the plan of care?

What resources does the provider have to evaluate his or her own value clarification process? Which provider from the health care team has more wisdom or experience dealing with emerging family structures, and how members relate (process)?

What resources does the provider have to evaluate his or her own value clarification process? Which provider from the health care team has more wisdom or experience dealing with emerging family structures, and how members relate (process)?

FIGURE 2.1

Essential tension and anticipated bias between the provider and the client in the working relationship. Relational space for mutual understanding is developed via the identification and minimization of bias.

How does the health care team return to the patient to evaluate if the health care interventions are helpful?

How does the health care team return to the patient to evaluate if the health care interventions are helpful?

VALUE ORIENTATION AND HEALTHY FUNCTIONING IN THE FAMILY

VALUE ORIENTATION AND HEALTHY FUNCTIONING IN THE FAMILY

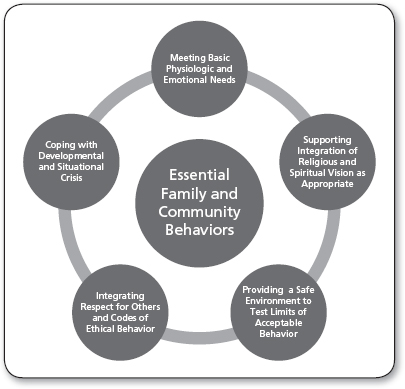

Despite differences in the expression of family life in different cultures and/or in different geographic regions of a country, five value orientations have been identified that are shared universally by human families (Table 2.1). An awareness of the sharing of these values helps the provider assess healthy family functioning, and promotes the creation of a just culture of care (Mayer & Cronin, 2008). Another measurement of family health relates to how they function. Healthy families and healthy communities (extension of families) share attributes, as shown in Figure 2.3.

Universal Value Orientations of Families | |

| |

Sources: Adapted from Heater (2003); Ho, Rasheed, and Rasheed (2004).

Traditionally, the practice of primary care conceived of the patient as an individual who required treatment. The family was treated as an extension of the patient insofar as the individual’s illness might be communicated to other members. Some providers were also concerned about the impact of illness or treatment requirements on family members but, by and large, care delivery was individual rather than family focused. In Western medicine, this tradition was further underscored by society’s cultural belief in the primacy of individual rights and freedoms. Outside Western society, the group, including both immediate and extended family, may attempt to dictate the direction of care (Fontes, 2008; Malloch & Porter-O’Grady, 2010).

Traditionally, the provider may have seen the family as being comprised of individuals. The outcome of care delivered in this way may be disconnected from the care needs of an actual patient living within the context of a family or cultural group. Care that is family focused does not imply that all members are always entitled to know every aspect of each other’s primary care issues. The primary care provider must sometimes walk a fine line, balancing family support with individual privacy needs. Of greatest concern is to identify the patient’s preferred support network (PSN): the people (family or others) who will assist in meeting health-related goals and participate in the plan of care.

The assessment of all family members and their relationship to one another (family genogram) is not a practical clinical tool in primary care. The limited information gleaned from a genogram has little utility in an urgent (time-sensitive) primary care interaction. This being said, the most important aspect of the successful relationship is the identification of family–friends–strangers who can assist the patient with getting the services he or she needs (Andrews & Boyle, 2008; deChesnay & Anderson, 2008; Heater, 2003). This idea does not, of course, apply to people who choose not to develop a support network, or only want their closest relative, for example, to be their sole support.

PREFERRED SUPPORT NETWORK

PREFERRED SUPPORT NETWORK

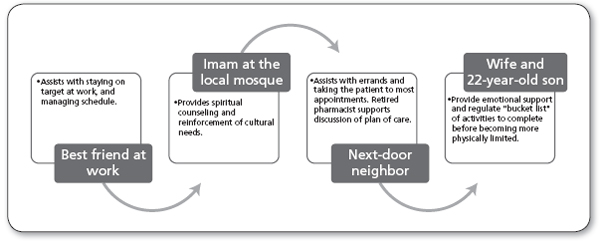

In actuality, patients who have a support network may rely on a vital core of four to six people for help. Asking the patient whom they would “call in an emergency,” or “who they can count on,” provides a significant insight into the patient’s PSN. Periodic evaluation of the PSN would allow staff to update changes to the person on whom the patient relies for physical, emotional, spiritual, and other needs related to his or her diagnosis. In the example in Figure 2.4, the client has five people in the PSN. The provider must remember, though, that the sensitive nature of confidential information must be respected at all times, and adhere to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) guidelines for all people.

Originally (Time 1), the patient had chosen his best friend at work, the imam at his mosque, the next-door neighbor, his wife, and his adult son to be his PSN. The best friend at work assists the patient with staying on target at work and managing his schedule. The imam at the local mosque provides spiritual counseling and reinforcement of cultural needs. The next-door neighbor assists with errands and taking the patient to most appointments. As a retired pharmacist, she also supports discussion of the plan of care. The wife and 22-year-old son provide emotional support and regulate the “bucket list” of activities (i.e., trips, activities) the patient wants to complete before he becomes more physically limited.

In 6 months, the PCN might be quite different. It is the responsibility of the provider to evaluate the functioning of the support system, and changes that should be understood as they relate to privacy, confidentiality, respite, and other concerns of team–interpersonal functioning. Figure 2.5 reveals the PSN as it may change, for example, due to the terminal nature of the patient’s condition. The PSN now involves four people (Figure 2.5—Time 2): a home care aide, a hospice chaplain, the neighbor next door, and the patient’s wife. The home care aide assists the wife with personal care, under the supervision of a home care registered nurse. The hospice chaplain provides spiritual counseling and pastoral care. The same next-door neighbor assists with errands and taking the patient to occasional appointments, as well as visiting to reminisce about life events. The wife provides physical and emotional support, while the 22-year-old son returns to school, as part of a respite plan.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree