Links: Codes & PV | BNP | Precipitating Events | S/s | Left | Right | Systolic | Diastolic | Etiology | Cardiomyopathy | Cor Pulmonale | W/u & Dx | Acute Tx | Admit / Refer criteria & Orders | Chronic Tx | Key Non-Pharmacologic Tx’s | Invasive Tx | Class / Stage / Prognosis | Hypotension | CAD | In AMI | Cardiogenic Shock |

When the heart or circulation is unable to meet metabolic demands of body at normal cardiac filling pressures. It can result from any structural or functional cardiac d/o that impairs the ability of the ventricle to fill with or eject blood. Can be acute, chronic, or acutely decompensated chronic. Because not all pt’s have volume overload at the time of initial or subsequent evaluation, the term “heart failure” is preferred over the older term “congestive heart failure” (CHF). It is the leading cause of hospitalization in age >65yo (20% of hospitalizations) in the USA.

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF): EF d40%. Also referred to as systolic HF. Randomized clinical trials have mainly enrolled patients with HFrEF, and it is only in these patients that efficacious therapies have been demonstrated to date.

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF): e50%. Also referred to as diastolic HF. Several different criteria have been used to further define HFpEF. The diagnosis of HFpEF is challenging because it is largely one of excluding other potential noncardiac causes of symptoms suggestive of HF. To date, efficacious therapies have not been identified.

NOTE: HF is not synonymous with either cardiomyopathy or LV dysfunction; these latter terms describe possible structural or functional reasons for the development of HF.

The prevalence of the condition increases with old age, approaching 10 of every 1,000 persons after age 65 years. Of pt’s hospitalized with HF, 80% are older than age 65 years. At age 65 years, 2% to 3% of US population has HF; after age 80 years, >80% do, has an annual mortality of 10% (NEJM 2007;356:1140-51).

• The lifetime risk of developing HF is 20% for Americans e40 years of age (J Am Coll Card 2013;10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.020).

ICD-9 Codes:

428.0 Congestive heart failure

428.1 Left heart failure

428.9 Heart failure, unspecified

425.1 Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy

425.4 Other primary cardiomyopathies

425.5 Alcoholic cardiomyopathy

425.7 Nutritional and metabolic cardiomyopathy

425.9 Secondary cardiomyopathy, unspecified

ICD-10 codes:

(I50.0) Congestive heart failure

(I50.1) Left ventricular failure

(I50.9) Heart failure, unspecified

(I51.0) Cardiac septal defect, acquired

(I51.1) Rupture of chordae tendineae, not elsewhere classified

(I51.2) Rupture of papillary muscle, not elsewhere classified

(I51.3) Intracardiac thrombosis, not elsewhere classified

(I51.4) Myocarditis, unspecified

(I51.5) Myocardial degeneration

(I51.6) Cardiovascular disease, unspecified

(I51.7) Cardiomegaly

(I51.8) Other ill-defined heart diseases

(I51.9) Heart disease, unspecified

Recommend ations of the Prevention of Heart Failure:

(Circulation 2008; 117:2544)

1. In the U.S., heart failure is the most common cause of hospitalization in Medicare-eligible adults and is estimated to account for more than $33 billion in healthcare expenditures annually. The lifetime risk for developing heart failure (per the Framingham study) exceeds 20% at age 40.

2. Factors contributing to the increasing prevalence of heart failure in developed countries include the aging of the population and improved care of patients with cardiovascular disease. In developing nations, increases in cardiovascular risk factors and diseases contribute to rising heart failure prevalence.

3. Despite the high prevalence of risk factors for heart failure, routinely screening asymptomatic persons at risk, using either LV function assessments or BNP assessment, cannot be recommended.

4. Heart failure is a final common pathway of several risk factors and cardiovascular diseases. Major risk factors include aging, hypertension, MI, diabetes, valvular disease, and obesity. In some persons, toxins (e.g., anthracyclines) or genetic polymorphisms contribute to heart failure risk. Minor risk factors include chronic kidney disease, sleep disordered breathing, smoking, and dyslipidemia.

5. Interventions to prevent cardiovascular events also reduce heart failure risk. Thus, medications — including ACEi’s, beta-blockers, antiplatelet agents, and statins — should be employed aggressively to guideline-recommended targets in patients with established atherosclerotic disease, dyslipidemia, hypertension, or diabetes.

6. Strategies to prevent or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus are likely to effectively reduce the incidence of heart failure.

7. Although still unproven to reduce heart failure incidence, glucose control in patients with established diabetes, smoking cessation, and measures to achieve and maintain normal body weight are probably important. Treatment of sleep disordered breathing and prevention of chronic kidney disease may also be useful.

8. Hypertension is clearly associated with increased risk for heart failure, highlighting the importance of achieving guideline-recommended blood pressure goals. Treating isolated systolic hypertension, although challenging, reduces incidence of heart failure even among the oldest old. When treated according to guidelines, blacks achieve the same level of blood pressure control as do non-Hispanic whites.

9. Current understanding of heart failure is suboptimal among both professionals and the public. Increasing awareness facilitates appropriate diagnosis, referral, and treatment.

Precipitating Causes of CHF: See Cardiomyopathy | Pulmonary embolism, AMI, dysrhythmia, poorly controlled HTN (high pulse pressure and high SBP both a greater risk than DBP, HTN precedes HF in 91% of cases), noncompliance with meds, high Na/ fluid intake, meds (beta-blocker, cardiotoxins, NSAIDs, corticosteroids, androgens, estrogens, TCA’s, cocaine). CHF may occur as the total cumulative dose of doxorubicin approaches 550 mg/m2. Pregnancy, high output states (fever, hyperthyroid, anemia, AV fistula, infection, Paget’s, Thiamine def), ETOH, endocarditis, renal failure, obesity. Trastuzumab (Herceptin) therapy to a significantly increased risk of cardiotoxicity per FDA in 9/05.

• Ramipril reduces the risk of development of heart failure in high-risk (CAD, DM, PVD, stroke) pt’s with normal EF by 23% (Circulation 2003;107:1278-1284).

• Low Vit-D status may be a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of CHF (J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1:105-12). NSAID therapy may increase the risk of heart failure by 60% (Epidemiology 2003;14:240-246), this risk was greater during the first month of medication and was independent of tx indication, the most common of which was for osteoarthritis. LVH and increased LV mass (particularly eccentric LVH) predicts subsequent heart failure (J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:2207-15).

• Retinopathy is an independent risk factor for CHF, even in the absence of preexisting heart disease, HTN or diabetes (JAMA 2005;293:63-69).

• Pt’s with subclinical hypothyroidism show changes in cardiac pump performance (lower stroke volume and cardiac output) that resolve with thyroid hormone replacement therapy (J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:439-445).

Low T3 levels are an independent predictor of mortality in pt’s with chronic heart failure (Am J Med 2005;118:132-6).

• Impaired insulin sensitivity independently predicts mortality in pt’s with otherwise stable CHF (J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:1019-1028).

Atrial fibrillation is associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes in chronic heart failure pt’s with a broad range of EF’s (J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:1997-2004). CHF can be seen with imatinib (Gleevec, Glivec) (Nat Med. Published online July 24, 2006).

• Current NSAID use is associated with a slightly increased risk of a first hospitalization for heart failure 7.3-fold (Heart 2006;92:1610-1615)….similarly, NSAID use worsens preexisting heart failure. Parental history of heart failure is a risk factor for heart failure (70% increase in risk per Framingham Heart Study) (NEJM. 2006;355:138-147)…. support current guideline recommendations for routine echocardiographic surveillance of people who are at risk for HF, in conjunction with lifestyle modification and aggressive management of comorbidities. CHF is a complex clinical syndrome that is the end result of a wide variety of pathophysiologic processes.

• Originally, CHF was seen primarily as a hemodynamic phenomenon due to low cardiac output and elevated filling pressures (Congestive Heart Failure 2006;12;6:302-306)…More recent understanding of HF has been dominated by a neurohormonal model, which suggests that maladaptive activation of a variety of neurohormonal pathways is a primary driver of HF progression.

Findings from the CARDIA study reveal a much higher incidence of heart failure in young (18 to 30yo) blacks than in young whites (NEJM 2009;360:1179)…..At baseline, blacks who developed heart failure had higher mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures — and had a higher prevalence of hypertension — than did either blacks who did not develop heart failure or whites…..Of blacks who developed heart failure, 75% had hypertension by year 10, as compared with only 12% of blacks who did not develop heart failure.

• Higher levels of HCT, even within the normal range, were associated with an increased risk of developing HF in this long-term follow-up from the Framingham Heart Study (Am J Card 212;109:241-245)…..Hazards ratios for HF in the low–normal, normal, and high HCT categories were 1.27 (95% confidence interval 0.82 to 1.97), 1.47 (1.01 to 2.15), and 1.78 (1.15 to 2.75), respectively, compared to the lowest HCT category (p for trend <0.0001)……In lifetime nonsmokers, those in the highest HCT category (>45.0 for women, >49.0 for men) had >2 times the risk for HF…..There are several mechanisms by which HF and HCT could be associated. In studies of primary polycythemia vera, very high levels of HCT have been associated with increased blood pressure and risk of thrombosis. One mechanism is nitric oxide (NO) scavenging by hemoglobin, a decreased NO availability impairs flow-mediated dilation and may link increased HCT to the pathogenesis of hypertension and related disorders. Higher HCT levels are associated with a higher prevalence of concentric left ventricular hypertrophy and abnormal indices of diastolic function. The relation between HCT and cardiovascular risk may be mediated by erythropoietin (EPO).

Compliance: Not following dietary and medication recommendations leads to heart failure hospitalization in a substantial minority (10.3%) of patients according to data on more than 54,000 patients who were admitted to 236 hospitals over a period of 3 years (Am Heart J 2009;158:644-652)……Among the precipitating factors for heart failure admission were respiratory illness (13.1%), arrhythmia (11.26%), and acute coronary syndromes (8.39%).

Acute Heart Failure Ddx: AMI with MR, ischemia of papillary muscles, severe HTN, valvular dz, endocarditis, high output state, acute dilated cardiomyopathy.

Hx: Quick Screen: “FACES” Activity altered, Comfortable walking up one flight of stairs, Edema, Short of breath.

S/s: Links: Pulse Pressure | Valsalva | HJR | JVD | Venous Waveforms | W/u & Dx |

The cardinal manifestations of HF are dyspnea and fatigue, which may limit exercise tolerance, and fluid retention, which may lead to pulmonary and/or splanchnic congestion and/or peripheral edema. Some patients have exercise intolerance but little evidence of fluid retention, whereas others complain primarily of edema, dyspnea, or fatigue.

Presents on one of 3 ways: Decreased exercise tolerance, fluid retention (leg or abd swelling), or asymptomatic, but found to have evidence of cardiac enlargement or dysfunction during their evaluation for a d/o other than HF (AMI, arrhythmia or thromboembolic event). Some pt’s have exercise intolerance but little evidence of fluid retention, whereas others complain primarily of edema and report few sx’s of dyspnea or fatigue.

The B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP:) level is one of the most accurate predictors of the presence or absence of CHF. The best clinical predictor of CHF is increased heart size on CXR (81% accuracy), followed by a h/o CHF (75%). The most accurate finding on exam are rales (69% accuracy) and a h/o paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (accuracy of 60%). The physical exam may be unremarkable in pt’s with exacerbations of chronic CHF, there may be no LE edema and the lung exam is particularly unreliable. Examine the carotid upstroke as it is typically diminished. Cools extremities and delayed capillary refill often indicate hypoperfusion.

Dyspnea/ DOE –> from pulmonary congestion and LVH. The enlarged heart that develops in pt’s with CHF reduces lung capacity (Chest 2006;130:164-171).

Orthopnea –> SOB begins 30 min after recumbent (incr venous return from incr fluid load).

PND –> awakens from sleep (specific finding).

Cough –> usually postural, worse when supine and at night. Vs ACEi giving a cough that is paroxysmal, not related to posture and can range from a mild tickle to severe sx’s (resolves in 1-2wks after stopping).

Nocturnal angina as cardiac work increases from fluid load, Cheyne-Stokes Resp, fatigue, abd fullness, cough (worse when supine), nocturia, anorexia, LE edema (detect if extracellular volume >5L. 1+

Pitting Edema = 2mm deep, 2+ = 4mm, 3+ = 6mm, 4+ = 8mm deep), JVD.

Check for S3 with bell at LV impulse area, as seen in 70% of pt’s with EF <30%, associated with adverse outcomes including progression (NEJM 2001;345:8).

Unrecognized hypervolemia (volume overload): common in heart failure pt’s without edema and is associated with worse pt outcomes (Am J Cardiol 2004;93:1254-1259), these pt’s have lower EF’s and higher PCWP’s and are less likely to receive beta-adrenergic blockers. May clinically manifest as elevated jugular venous pressure, low BP and worsening renal function. Up to 60% of pt’s >55yo with an EF <25% are asymptomatic (Eur Heart J 1999;20:447-55).

Other: May hear an S4 if pt has LVH. Check for displaced LV impulse. PMI may be difficult to locate, best felt in L lateral decubitus position. Abnormal PMI in only 40%. To check for a displaced cardiac apex, the pt should be in the supine position or 45-degree-angle left lateral decubitus, palpate the 4th and 5th left intercostal space during expiration. The test is positive if the impulse is outside the midclavicular line. Among pt’s with CHF admitted to hospital, those with a body temperature on admission of <95.5 F (35.5 C) have a 4-fold increased risk of dying in the hospital (Am Heart J 2005;149:927-933).

Lungs: Only hear rales in 30% as lymphatics enlarge and drains fluid from the lungs. The absence of crackles provides little help in chronic CHF. Wheezes may be the sole manifestation (cardiac asthma).

CXR: pulmonary vasculature congestion (PVC) = cephalization. Often see enlarged heart, pericardial effusion (water bottle sing is a narrow segment involving the aorta with a broad pericardial sac). Dilated pulmonary arteries and hilar enlargement. Pleural effusions common.

Most, but not all, exudative effusions in CHF pt’s have causes other than heart failure (transudates might be “converted” into exudates by traumatic taps by aggressive diuresis or prior bypass surgery with persistent impairment of lymphatic clearance) (Chest 2002;122:1518-23).

8 predictors of CHF: elevated BNP (4 points), interstitial edema on CXR (2 points), orthopnea (2 points), absence of fever (2 points), loop diuretic use (1 point), age >75 years (1 point), rales (1 point), and absence of cough (1 point) (Am Heart J 2006;151:48-5).

Low risk (0–5 points), intermediate (6–8 points), or high (9–14 points) likelihood for heart failure. A score of 6 or more points had a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 84% for heart failure.

6 predictors of CHF in elderly pt’s with COPD: laterally displaced apex beat (3 points), history of ischemic heart disease (2 pts), HR >90 beats/min (2 pts), BMI >30 kg/m2 (3 pts), N-terminal pro-BNP >14.75 pmol/L (4 pts), and abnormal ECG (3 pts). The probability of CHF was 5%, 11%, 25%, and 57% among pt’s with 0 points, 2–5 pts, 6–9 pts, and 10–14 pts, respectively (BMJ 2005;331:1379-82).

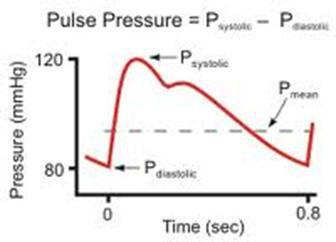

Pulse Pressure (PP): SBP – DBP.

A measure of arterial stiffness. Higher PP correlates with incr occurrence of cardiovascular events. If >45, then abnormal. Tends to rise after 5th decade due to arterial stiffness, this leads to incr afterload and myocardial O2 demand as less compliant and require a greater pressure to pack the stroke volume in them. For each 10mm Hg rise in PP –> 4% incr CHF, 12% incr CAD, 6% incr mortality (JAMA 1999; 281:7).

A measure of arterial stiffness. Higher PP correlates with incr occurrence of cardiovascular events. If >45, then abnormal. Tends to rise after 5th decade due to arterial stiffness, this leads to incr afterload and myocardial O2 demand as less compliant and require a greater pressure to pack the stroke volume in them. For each 10mm Hg rise in PP –> 4% incr CHF, 12% incr CAD, 6% incr mortality (JAMA 1999; 281:7).

Wide PP is also seen with AI, hyperthyroidism, low SVR (sepsis, cirrhosis/ dialysis shunts, ACEi, hydralazine), arteriosclerosis, fevers and increased intracranial pressure. Pulse pressure, but not mean pressure, is associated with an incr risk for fatal events (J Hypertens 2002;20:145-151).

• Higher pulse pressure in older adults is linked with increased risk for Alzheimer disease and dementia, which is probably caused by artery stiffness and severe atherosclerosis (Stroke 2003;34:594-9).

• High pulse pressure independently predicts progression of aortic wall calcification in pt’s with controlled hyperlipidemia (Hypertension 2004;43:536-540).

• PP followed by DBP and SBP were the best predictors of CVD mortality compared to age, physical activity, cholesterol and anthropometric indexes (Arch Int Med 2005;165:2142-47)….no differences observed among different populations studied.

• Pulse pressure is a predictor of new-onset AF, even after adjusting for other clinical variables, such as left atrial size and left ventricular mass (JAMA. 2007;297:709-715)…The cumulative 20-year AF incidence rates were 5.6% for those with a pulse pressure of 40 mm Hg or less and 23.3% for those with pulse pressure higher than 61 mm Hg. After adjusting for age and sex, a 20-mm Hg increase in pulse pressure was associated with a 34% increase in the risk of developing AF.

Proportional Pulse Pressure (PPP) <25% (=PP/SBP). Mean Arterial Pressure = (SBP + (DBP X 2))/ 3.

• A pulse pressure/systolic pressure ratio of less than 0.25 implicates a cardiac index of less than 2.2 L/min/m2 and a less favorable clinical outcome (JAMA. 1989;261:884–888).

• An elevated pulse pressure appears to be a risk factor for open-angle glaucoma (OR = 4.68) (Arch Ophthalmol 2007;125:805-812).

• Preoperative brachial pulse pressure, an index of vascular stiffness, is a strong predictor of stroke following cardiac surgery, and it is independent of chronological age (Hypertension 2007;50:630-635)….Stroke pt’s had a significantly higher average pulse pressure (81.2 mm Hg) compared with pt’s who did not have strokes (64.5 mm Hg)…..The unadjusted hazard ratio for stroke was 1.32 for every 10 mm Hg increase in pulse pressure. Increasing pulse pressure levels and higher baseline pulse wave velocity — indications of increased arterial stiffness — were linked with a decline in memory and concentration among aging individuals (Hypertension. Published online November 19, 2007).

• High pulse pressure in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) may help identify an increased risk for development of potentially fatal heart complications according to a retrospective study (Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;Published online January 28)……After multivariate adjustment, pulse pressure of more than 60 mm Hg predicted a CAC score of more than 0 (OR = 2.14), 100 or more (OR, 2.92), and 400 or more (OR, 6.17)…..the optimal cutoff value of pulse pressure was 60 mm Hg, yielding corresponding values for sensitivity and specificity of 51% and 69% for the presence or absence of CAC, 59% and 69% for a CAC score of 100 or more, and 75% and 69% for a CAC score of 400 or more, respectively.

High pulse pressure (>62.5 mm Hg) is an independent predictor of mortality among very old hospitalized patients prospective study indicates (J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:893-896)…..pulse pressure remained a significant, independent predictor of all-cause mortality only among older (>80yo) patients (HR 1.82).

Tx: Lisinopril (10 mg) and valsartan (80 mg), with or without hydrochlorothiazide (6.25 mg), are more effective in reducing pulse pressure than are a number of other agents (amlodipine, indapamide or atenolol) (Cardiovasc Ther 2009;27:4-9).