EYE: RED EYE

ATIMA C. DELANEY, MD AND ALEX V. LEVIN, MD, MHSc, FRCSC

“Red eye” is a generic term that refers to any condition in which the “white of the eye” appears red or pink. A red eye may be caused by local factors, intraocular disease, or systemic problems. Tables 22.1, 22.2, and 22.3 list common and life-threatening causes of red eye. The cause of a red eye can often be identified by the history alone. The history should include the presence or absence of pain, foreign-body sensation, itching, discharge, tearing, photophobia, onset, visual disturbances, recent illnesses, and trauma. The examination should include visual acuity, pupil shape and reactivity, the gross appearance of the sclera and conjunctiva, extraocular muscle function, and palpation of preauricular nodes. The evaluation often requires fluorescein staining and slit lamp examination by an experienced provider.

Discussion here, of chemical conjunctivitis or irritation caused by agents such as smoke or trauma, is limited because the history often makes the diagnosis clear. The management of these disorders is discussed in Chapters 122 Ocular Trauma and 131 Ophthalmic Emergencies.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The term conjunctivitis should be reserved for disorders in which the conjunctiva is inflamed. Inflammation may be caused by direct irritation, infection, abnormalities of underlying or contiguous structures (e.g., cornea), immune phenomena, or processes secondary to abnormalities of the lid and lashes. Inflammation within the anterior chamber affecting the iris (iritis) may also result in secondary inflammation of the conjunctiva.

The sclera may become inflamed (scleritis). An intermediate layer, the episclera, lies beneath the conjunctiva’s substantia propria and another largely avascular fascial layer (Tenon’s fascia), where it is firmly attached to the sclera. The episclera is more vascularized than the sclera and may become inflamed either in a diffuse or localized fashion (diffuse, sectorial, or nodular episcleritis).

A tear film, which prevents desiccation, is constantly present over the surface of the eye. A disruption in the function of the anatomic structures of the tear film may cause desiccation of the ocular surface, resulting in irritation and inflammation (dry eye syndrome).

Innervation of the conjunctiva and cornea comes from the first division of the trigeminal nerve (V1). Abnormalities on the ocular surface may give rise to pain or a foreign-body sensation. The reflex arc that involves the afferent trigeminal nerve and the efferent facial nerve results in a rapid blink, with contraction of the orbicularis oculi muscle, to protect the surface of the eye in response to noxious stimuli. Two other reactions to noxious stimuli may occur: tearing and discharge. Tearing (epiphora) may accompany virtually any conjunctival inflammation or irritation. Tearing may even be a part of some forms of dry eye syndrome, as the lacrimal gland attempts to compensate for ocular surface. Discharge from the eye results either from conjunctival exudation or precipitation of mucus out of the tear film. The latter occurs when the tear film is not flowing smoothly (e.g., nasolacrimal duct obstruction), causing misinterpretation as infection when the problem is actually mechanical. Although discharge may be a nonspecific finding, the nature of the discharge may be helpful in the cause of an inflammation or infection. The presence of membranes or pseudomembranes (Fig. 22.1) is more common with adenovirus infection or Stevens–Johnson syndrome. These white or white–yellow plaques are caused by loosely or firmly adherent collections of inflammatory cells, cellular debris, and exudate.

EVALUATION AND DECISION

The approach to the child who presents in the emergency department with a red eye is outlined in the flowchart shown in Figure 22.2.

Any child who wears contact lenses regularly, even if the lens is not in the eye at the time of the examination, should be referred to an ophthalmologist within 12 hours if he or she has red eye. Red, and often painful, eyes of a person who wears contact lenses may represent potentially blinding corneal infection (corneal ulcer) or the breakdown of the corneal epithelium, which would predispose the person to subsequent corneal infection. Other than removing the contact lens when possible (topical anesthesia may be helpful), further diagnostic or therapeutic interventions by the pediatric emergency physician are not indicated in these patients without direct consultation with an ophthalmologist. Decisions regarding starting empiric antibiotics should be made with an ophthalmologist, as there may be benefit to waiting until corneal cultures can be obtained. The presence of a white spot on the cornea of a contact lens wearer with inflamed conjunctiva is an ominous sign that may represent an ulcer. The absence of such a spot does not rule out corneal ulcer. Other causes of red eye in a contact lens wearer include contact lens solution allergy (which may develop even after years of using the same regimen), overwearing of contact lenses, overly tight fit, foreign body, or a damaged contact lens. Examination by an ophthalmologist is perhaps the only way to ensure that a corneal ulcer is not missed by ascribing the red eye to one of these other etiologies. It is therefore recommended that all contact lens wearers with a red eye be seen by an ophthalmologist.

Numerous systemic diseases may be associated with ocular inflammation. A representative sample can be found in Table 22.3. In some systemic diseases, the associated ocular abnormality involves intraocular inflammation (iritis, vitritis), which can then cause secondary conjunctival infection or inflammation. Patients with these diseases may also have coincidental ocular inflammation unrelated to their underlying conditions. Ophthalmology consultation may be helpful in making this distinction. For example, in Kawasaki disease, the inflammation of the conjunctiva may be associated with mild iritis. More often, the conjunctiva is inflamed in isolation as part of the systemic mucous membrane involvement. The conjunctivitis of Kawasaki disease is usually confined to the bulbar conjunctiva, often with limbal sparing (Fig. 22.3), with little or no discharge. In contrast, the bulbar and palpebral conjunctiva are inflamed in infectious conjunctivitis (Fig. 131.7).

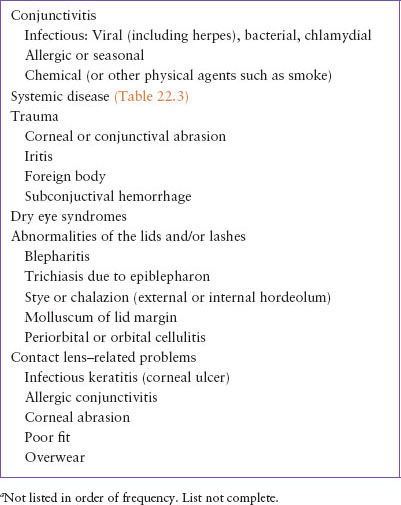

TABLE 22.1

COMMON CAUSES OF RED EYEa

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree