Emergency Evaluation of Important Ocular Symptoms

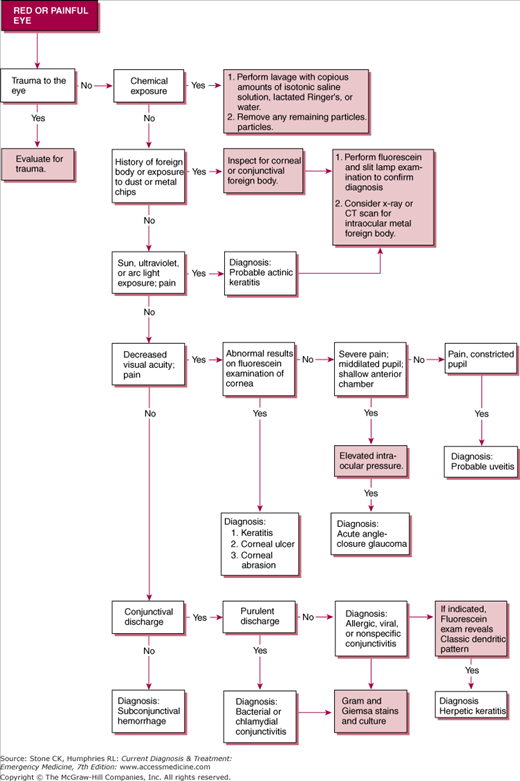

See Figure 31–1 and Table 31–1.

| History and Clinical Findings | Conjunctivitis | Iritis | Acute Glaucoma | Corneal Infection (Bacterial Ulcer) | Corneal Erosion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | Extremely common | Common | Uncommon | Uncommon | Rare |

| Onset | Insidious | Insidious | Sudden | Slow | Sudden |

| Vision | Normal to slightly blurred | Slightly blurred | Markedly blurred | Usually blurred | Blurred |

| Pain | None to moderate | Moderate | Severe | Moderate to severe | Severe |

| Photophobia | None to mild | Severe | Minimal | Variable | Moderate |

| Nausea and vomiting | None | None | Occasional | None | None |

| Discharge | Moderate to copious | None | None | Watery | Watery |

| Ciliary injection | Absent | Present – perilimbal | Present | Present | Present |

| Conjunctival injection | Severe diffuse in fornices | Minimal | Minimal, diffuse | Moderate, diffuse | Mild to moderate |

| Cornea | Clear | Usually clear | Steamy | Locally hazy | Hazy |

| Stain with fluorescein | Absent | Absent | Absent | Present | Present |

| Hypopyon | Absent | Occasional | Absent | Occasional | Absent |

| Pupil size | Normal | Constricted | Middilated, fixed, and Irregular | Normal | Normal or constricted |

| Intraocular pressure | Normal | Normal | Elevated | Normal | Normal |

| Gram-stained smear | Variable; depending on cause | No organisms | No organisms | Organisms in scrapings from ulcers | No organisms |

| Pupilary light response | Normal | Poor | None | Normal | Poor to normal |

Historical factors are important in determining the cause of ocular complaints. History, when correlated with characteristic ocular findings on focused physical examination, usually makes the diagnosis. History should include use of eye drops, previous episodes, onset of pain, contact lens use, systemic illnesses and findings, and associated symptoms.

The components of a complete eye examination include the following.

Visual acuity testing using a standard acuity chart (Snellen). An acute change in vision usually indicates disease of the eyeball globe or visual pathway. Pain and decreased acuity indicate corneal disease, acute angle-closure glaucoma, or iritis.

Inspection of the eye to include conjunctiva, cornea, sclera, lens, and pupil, external lids, lashes, lacrimal ducts, orbits, and periorbital areas for sign of trauma, infection, exudate, or irritation.

Check pupillary function for shape, symmetry, and reactivity to light and accommodation.

Extraocular muscle function for any signs of entrapment or palsy.

Check for abnormalities in the visual fields; this is generally done in the emergency department by confrontation.

Direct fundoscopy is generally used to check the retina, optic disc, and retinal vessels.

Slit-lamp examination should be done before and after fluorescein staining to check for corneal abnormalities and examine the anterior chamber.

Intraocular pressure (IOP) can be tested with a Tono-Pen or Schiotz tonometer (described later in this chapter). Abnormally high pressure may be grossly estimated by palpation, ie, tactile tonometry.

Further diagnostic studies including blood tests, cultures, plain X-rays, bedside ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) scan, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the orbits may be needed to definitively establish a diagnosis.

Patients thought to have acute ocular conditions that may permanently decrease visual acuity (eg, acute angle-closure glaucoma) should have urgent ophthalmologic consultation. Patients with other conditions may receive treatment and be discharged with appropriate follow-up.

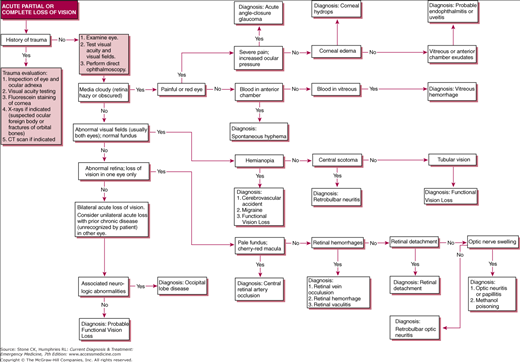

See Figure 31–2.

Exclude trauma as a cause of visual loss. Both blunt and penetrating ocular injuries may result in blindness.

Obtain a history from the patient (rate of onset of visual loss; whether it is unilateral or bilateral, painful or painless, with or without redness). Ophthalmologic examination should emphasize visual acuity and visual field testing.

Cloudy media will may completely obscure the retina (red reflex blunted or absent) or will make it impossible to visualize retinal landmarks such as the optic disc. Chronic causes of hazy media are common (eg, cataracts) and may complicate the evaluation of acute visual loss.

Grossly abnormal visual fields are usually caused by central nervous system disease and thus generally affect both eyes (not always to the same degree). The retinas are usually normal on ophthalmoscopic examination.

Hemianopia is usually due to postchiasmal neurologic disorders (eg, tumor, aneurysm, migraine, stroke), in which case other acute neurologic lesions are present as well. Rarely, it is psychogenic functional in origin.

A central scotoma indicates isolated macular involvement typical of retrobulbar neuritis and may or may not be associated with pain.

Tubular vision not in conformity with the laws of optics is characteristic of psychogenic functional visual loss.

An abnormal retina, usually in the eye with visual loss, is characteristic of several rare but serious conditions.

In central retinal artery occlusion, the fundus is usually pale with a cherry-red fovea. This is a medical emergency (see below).

Central retinal vein occlusion is associated with multiple widespread retinal hemorrhages.

Retinal hemorrhage from other causes (eg, anticoagulation) may produce visual loss.

Retinal detachment produces visual loss preceded by visual flashes. If visual acuity is affected, detachment is large and may be easily visible on direct ophthalmoscopy; however, small detachments may require indirect ophthalmoscopy for visualization. Flashes of light may also occur in patients with migraine or as a result of posterior vitreous detachment.

Causes of acute visual loss are listed and discussed below.

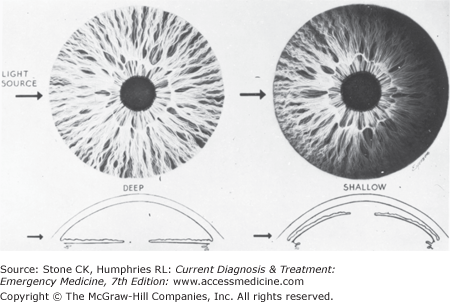

Acute angle-closure glaucoma causes corneal edema, but the more striking findings are eye pain; pupils fixed in mid position or dilated, often with irregular margins; a shallow anterior chamber angle (Figure 31–3); hyperemic conjunctiva; and significantly increased IOP. Acute angle-closure glaucoma is a medical emergency (see below).

Severe corneal edema of diverse causes (eg, abrasion, keratitis, postoperative) may cause visual loss with eye pain.

Hyphema is the presence of blood in the anterior chamber. This is generally traumatic in nature, although spontaneous hyphema may occur especially in patients on anticoagulant medications.

Vitreous hemorrhage causes painless visual loss due to accumulation of blood in the posterior chamber. The anterior chamber is clear. The red reflex is often absent.

Endophthalmitis (intraocular infection) is a rare condition usually associated with eye pain and decreased visual acuity. Eye examination will disclose pus in the anterior chamber (hypopyon) or vitreous. Systemic illnesses associated with endophthalmitis include ankylosing spondylitis, ulcerative colitis, other seronegative arthropathies, sarcoidosis, toxoplasmosis, tuberculosis, syphilis, and herpes zoster.

Patients with sudden visual loss due to ocular disease should have ophthalmologic consultation.

Ocular Conditions Requiring Immediate Treatment

- Acute onset of moderate to severe, unilateral eye pain with associated nausea and vomiting

- Perilimbal eye redness with a mid-dilated, unreactive, irregular pupil

- Increased IOP confirms diagnosis

Acute angle-closure glaucoma results from a sudden increase in IOP from blockage of the anterior chamber angle outflow channels by the iris root. This sudden rise in IOP causes intraocular vascular insufficiency that may lead to optic nerve or retinal ischemia and can cause permanent vision loss within hours. Prompt management is needed to minimize the likelihood of permanent vision loss.

Acute angle-closure glaucoma is characterized by sudden onset of blurry vision, followed by severe pain, halos around lights, photophobia, frontal headache and nausea and vomiting. Other findings include a red eye with fixed or sluggish mid-dilated pupil, shallow anterior chamber, and hazy cornea. IOP will be greater than 30 mm Hg. Risk factors include myopia, hyperopia, shallow anterior chamber, narrow angle, and anterior placement of lens.

(See Figure 31–2 and Table 31–1.) In iridocyclitis (iritis), IOP is normal and the pupil is small. In conjunctivitis, IOP is normal and the pupil is not affected. Corneal ulcer is diagnosed by fluorescein staining of the cornea.

Acute angle-closure glaucoma is an emergency. Timely treatment is important. Obtain ophthalmologic consultation for emergency management and reduce the IOP by one or more of the following means:

- Timolol, 0.5%, one drop in the affected eye

- Pilocarpine, 2% eye drops, two drops every 15 minutes for 2–3 hours

- Mannitol, 20%, 250–500 mL intravenously over 2–3 hours

- Acetazolamide, 500 mg orally or 250 mg intravenously

Glycerin, 1g/kg orally in cold 50% solution mixed with chilled lemon juice. Give sedation, antiemetics, and analgesics as necessary to control pain nausea and agitation.

Acute angle-closure glaucoma calls for urgent initiation of medical therapy and ophthalmologic consultation.

- Sudden, painless complete loss of vision in one eye

- Ophthalmoscopy demonstrates pallor of disc, retinal edema, cherry-red fovea, and “boxcar” appearance of retinal veins

- Treatment should be initiated immediately

Central retinal artery occlusion is most commonly embolic in origin. Vision loss can occur in as little as 90 minutes from time of onset. Mitigating factors include occlusion time, cilioretinal artery patency, and cause of the occlusion.

There is typically a history of sudden, complete, painless loss of vision in one eye, usually in an older person or others at risk for thromboembolic disease. Ophthalmoscopic examination discloses pallor of the optic disc, edema of the retina, cherry-red fovea, bloodless constricted arterioles that may be difficult to detect, and “boxcar” segmentation of blood in the retinal veins.

Central retinal artery occlusion is an emergency. Vision may be permanently lost in as short as 90 minutes, although visual recovery has occurred up to 3 days after occlusion. It is recommended that treatment be started if the patient is seen within 24 hours of symptom onset.

Treatment measures consist of ocular massage (moderate pressure for 10 seconds and release for 5 seconds), timolol ophthalmic, intravenous acetazolamide, or inhaled carbogen (oxygen–carbon dioxide mixture of 95% oxygen and 5% carbon dioxide). Other modalities to be considered by ophthalmology are direct infusion of thrombolytics in the ophthalmic artery or anterior chamber paracentesis. Hyperbaric treatment may be beneficial, if available.

Ophthalmologic consultation should be obtained on an emergency basis.

- Periorbital swelling and redness

- Painful, limited extraocular movement

- Intravenous antibiotics and admission

Acute infection of the orbital tissues is generally caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, other streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, and (previously, chiefly in children) Haemophilus influenzae. Less frequently, certain fungi of the Phycomycetes group may cause orbital infections (rhinoorbitocerebral mucormycosis) in diabetics. Most causative organisms enter the orbit by direct extension from the paranasal sinuses (primarily ethmoid) or through the vascular channels draining the periorbital tissues. Rarely, infection may spread to the cavernous sinus or meninges.

There may be a history of sinusitis or periorbital injury, pain in and around the eye, and possibly reduced visual acuity. Examination may demonstrate swelling and redness of the eyelids and periorbital tissues, chemosis of the conjunctiva, rapidly progressive exophthalmos, and ophthalmoplegia. Disc margins may be blurred, and fever is commonly present. Radiographic evaluation may demonstrate sinusitis with or without soft tissue orbital infiltration.

Patients with invasive infection due to the Phycomycetes group (Mucor, Rhizopus, and other genera) may present with rapidly progressive orbital cellulitis, often with cavernous sinus thrombosis. Diabetic and immunocompromised patients are at increased risk. Examination often reveals coexisting maxillary and/or ethmoid sinusitis and palatal or nasal mucosal ulceration.

Obtain cultures of blood and periorbital tissue fluid. Obtain CT scan of the orbit to rule out orbital abscess and intracranial involvement. Patients should be admitted and appropriate broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics started (ceftriaxone 1–2 g IV plus vancomycin 1 g IV or piperacillin/tazobactam 3.375 g IV). Obtain immediate ophthalmologic and or otolaryngologic (ENT) consultation. Patients with orbital phycomycosis are given intravenous amphotericin B and require surgical intervention for debridement of infected tissue. Neurosurgical consultation may be needed for any intracranial involvement.

- Complication from facial or sinus infections

- Decreased vision associated with headache, nausea, fever, chills, and other signs of systemic infection

- Early administration of parenteral antibiotics

Cavernous sinus thrombosis is usually associated with orbital and ocular signs and symptoms. The infection results from hematogenous spread from a distant site or from local extension from the throat, face, paranasal sinuses, or orbits. Cavernous sinus thrombosis starts as a unilateral infection and commonly spreads to involve the other cavernous sinus.

The patient may complain of chills, headache, lethargy, nausea, pain, and decreased vision. Fever, vomiting, and other systemic signs of infection may be present. Ophthalmologic examination discloses unilateral or bilateral exophthalmos, absent pupillary reflexes, and papilledema. Involvement of the third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerves or of the ophthalmic branch of the fifth nerve leads to limitation of ocular movement and decrease in corneal sensation.

Obtain blood cultures and start appropriate antibiotics (nafcillin, plus a third-generation cephalosporin). Consider vancomycin if methicillin-resistant S. aureus is suspected or prevalent. Obtain CT scan of the head and orbits. Seek ophthalmologic, neurologic, and medical consultation early. Although controversial, anticoagulation with heparin can be safely considered for patients with a deteriorating clinical condition after excluding intracranial hemorrhage radiologically.

- Pus in anterior chamber (hypopyon) is diagnostic

- Obtain emergency ophthalmology consultation for drainage and antibiotic treatment

Endophthalmitis is an acute microbial infection confined within the globe. Infection involving the sclera as well as other intraocular structures is called panophthalmitis. Infections of the globe can be exogenous or endogenous. Exogenous infection results from penetrating injury or may follow intraocular surgery or a ruptured corneal ulcer. Endogenous infection by the hematogenous route is less common and may be accompanied by fever and chills.

The patient complains of pain, blurred vision, and photophobia. Examination discloses redness and chemosis of the conjunctiva, swelling of the eyelid, hypopyon (pus in the anterior chamber), and cloudy media (fundus hazily seen, or absent red reflex).

Send blood culture, obtain emergency ophthalmologic consultation, and give sedation and analgesics. The patient may have to undergo anterior chamber tap and vitreous aspiration (by an ophthalmologist). Send specimens obtained for staining with Giemsa and Gram stains and for cultures on appropriate media.

Check stained smears of ocular fluid, and if no organisms are seen, give empiric subconjunctival and systemic antibiotics (vancomycin and an aminoglycoside or third-generation cephalosporin) while results of culture are pending.

- Painless decrease in vision

- History of flashes of light, then “curtain” in visual field

- Urgent consultation for surgical repair

Detachment of the retina is actually separation of the neurosensory layer from the retinal pigment epithelium. Sub-retinal fluid accumulates under the neurosensory layer. Detachment may become bilateral in one-fourth of cases. Retinal detachment is more common in older people and in those who are highly myopic. Hereditary factors may also play a role. Three types of primary retinal detachment are recognized: (1) rhegmatogenous detachment (most common), from retinal holes or breaks; (2) exudative detachment, usually from inflammation; and (3) traction detachment, which occurs when vitreous bands pull on the retina.

Minimal to moderate trauma to the eye may cause retinal detachment, but in such cases predisposing factors such as changes in the vitreous, retina, and choroid play an important role in pathogenesis. Severe trauma may cause retinal tears and detachment even if there are no predisposing factors.

The patient complains of painless decrease in vision and may give a history of flashes of lights or sparks. Loss of vision may be described as a curtain in front of the eye or as cloudy or smoky. Central vision may not be affected if the macular area is not involved; this frequently causes a delay in seeking treatment. Patients in whom the macula is detached present to the emergency department with sudden deterioration of vision.

IOP is normal or low. The detached retina appears gray, with white folds and globular bullae. Round holes or horseshoe-shaped tears may be seen by indirect ophthalmoscopy in the rhegmatogenous detachment. Vitreous bands or other changes may be seen in the traction type of detachment.

Primary retinal detachment should be differentiated from detachment secondary to other causes, for example, from preeclampsia–eclampsia or tumors of the choroid.

Arrange for referral to an ophthalmologist. If the macula is attached and central visual acuity is normal, urgent surgery, which is successful in about 80% of cases, may be indicated. If the macula is detached or threatened, operation should be scheduled on an urgent basis, because prolonged detachment of the macula results in permanent loss of central vision.

A wide variety of organic chemicals may lead to visual deterioration. Ingestion of chemicals that cause corneal or lenticular opacities usually leads to insidious onset of visual loss. Ingestion of compounds that cause damage to nervous tissue may lead to slow or rapid deterioration of vision. Exposure to toxic doses of methanol, halogenated hydrocarbons (eg, methyl chloride), arsenic, and lead may cause permanent visual damage. Acute or chronic administration of drugs such as ethambutol, chloramphenicol, quinine, and salicylates may also cause optic neuritis and loss of vision.

By far the most common toxic cause of blindness is methanol (methyl alcohol). Ingestion of only a few milliliters may cause permanent blindness. Acute methanol poisoning causes nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Headache, dizziness, and delirium may occur. Loss of vision may be complete and sudden within a few hours after drinking methanol or may occasionally be noted about 3 days after exposure. Pupillary reflexes are sluggish. Ophthalmoscopic examination shows swelling and hyperemia of the optic nerve head, distention of the veins, and peripapillary edema of the retina.

Hospitalize the patient immediately. See Chapter 47 for details of evaluation and treatment.

Nontraumatic Ocular Emergencies

- Swelling, redness, and tenderness over the lacrimal sac on the lateral, proximal aspect of the nose

- Warm compresses and systemic antibiotics for treatment

Acute infection of the lacrimal sac occurs in children and adults as a complication of nasolacrimal duct obstruction. The most frequently encountered causative organism is S pneumoniae.

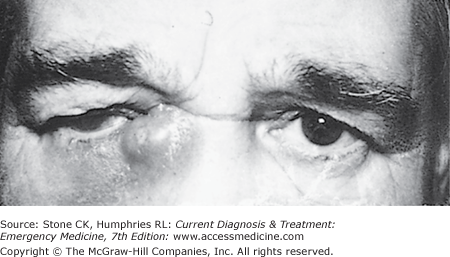

The patient complains of pain. There may be a history of tearing and discharge. Examination discloses swelling, redness, and tenderness over the lacrimal sac (Figure 31–4).

Pus should be collected, for Gram-stained smear and culture, by applying pressure over the lacrimal sac.

Begin systemic antibiotics with cephalexin or amoxicillin–clavulanate. Topical antibiotic drops may also be used, but not alone. Use warm compresses 3–4 times daily. Consider incision and drainage of a pointing abscess.

The patient can be discharged to home care with a prescription for systemic antibiotics and instruction in how to apply warm local compresses. Consult an ophthalmologist for consideration of surgical correction. The patient should be seen again within 1–3 days.

- Swelling, erythema, and pain at the lacrimal gland located at the temporal aspect of the upper eyelid

Infection and inflammation of the lacrimal gland is characterized by swelling, pain, tenderness, and redness over the upper temporal aspect of the upper eyelid.

Acute dacryoadenitis must be differentiated from viral infection (mumps), sarcoidosis, Sjögren’s syndrome, tumors, leukemia, and lymphoma.

Purulent bacterial infections should be treated by incision and drainage of localized pus collections, antibiotics, warm compresses, and systemic analgesics. Viral dacryoadenitis (mumps) is treated conservatively.

The patient should be referred to an ophthalmologist for follow-up care in 2–3 days.

- Pain and redness with swelling over the eyelid

- Warm compresses and topical antibiotic three times daily

Acute hordeolum is a common infection of the lid glands: the meibomian glands (internal hordeolum) and the glands of Zeis or Moll (external hordeolum). The most frequent causative organism is S. aureus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree