Evaluation of the Solitary Pulmonary Nodule

Solitary pulmonary nodules are incidental findings on chest x-ray or computed tomography (CT) images. They are defined as round lesions less than 3 cm in diameter and surrounded by pulmonary parenchyma and without other abnormal findings. Such nodules are found at a rate of 1 to 2 per 1,000 routine chest radiographs. They are found more frequently on chest CT images and are becoming increasingly frequent with use of low-dose CT to screen for lung cancer. The discovery is a worrisome finding for both patient and clinician because it raises the possibilities of primary lung cancer and solitary metastasis from a nonpulmonary source. The patient is usually asymptomatic and undergoing chest radiography for either an unrelated issue or screening. Granulomas and hamartomas account for the majority. Historically, about 30% proved to be malignant, but with the identification of increasingly smaller nodules on CT images, the proportion that is malignant is declining.

Pulmonary malignancies with the greatest potential for cure present as solitary nodules. Consequently, thorough assessment is of the utmost importance. On the other hand, the vast majority of these lesions are not cancers, and to subject all patients to invasive studies and excision can lead to much unnecessary morbidity.

The primary physician in consultation with radiologic colleagues needs to determine the likelihood of malignancy on the basis of clinical and radiographic findings and identify the patient who requires referral for consideration of advanced imaging, transthoracic fine needle aspiration biopsy, bronchoscopy, or surgery, which may be either thoracotomy or videoassisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). Most of the workup can be performed on an outpatient basis.

Solitary pulmonary nodules characteristically appear in the middle or lateral lung fields surrounded by normal lung and unaccompanied by satellite lesions. They have smooth contours and are usually round (“coin” lesions) or oval. Neoplastic, granulomatous, vascular, and cystic processes are the principal pathologic mechanisms responsible for nodule formation. The nodule displaces normal aerated lung parenchyma and does not cause symptoms unless airway obstruction, pleural invasion, interference with respiratory mechanics, or involvement of blood vessels or nerves occurs. Inflammatory lesions double in volume in less than 5 weeks, malignancies take between 1 and 18 months to double, and benign nodules take longer. A solitary nodule that does not change in size for 2 years has traditionally been considered benign, but some cancers, including bronchoalveolar cell carcinomas, can appear stable for that long. In fact, one study suggested that the absence of appreciable growth over a 2-year period had a predictive value of only 65% for a benign lesion.

The older the patient, the greater are the chances that the nodule is malignant; the probability is less than 2% for patients younger than age 30 years and increases by 10% to 15% with each succeeding decade. A history of smoking greatly increases the probability that the nodule is malignant, as does concurrent weight loss, headache, or bone pain. The size of the nodule has also become increasingly important in discriminating benign from malignant lesions as use of chest CT for screening and diagnosis has increased and smaller-diameter lesions are discovered incidentally. More than 99% of noncalcified lesions less than 4 mm in diameter are benign, as are approximately 94% of noncalcified lesions between 4 and 8 mm in diameter. However, as many as 50% of lesions greater than 8 mm in diameter prove to be malignant in some series.

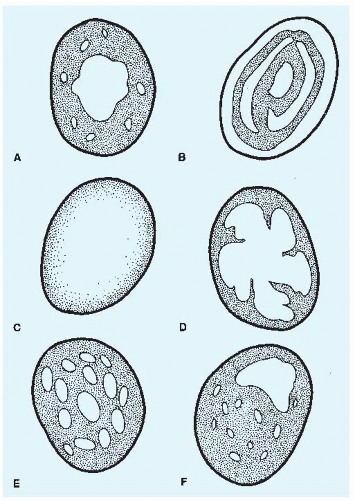

Benign and malignant solitary lung nodules may have a similar appearance on chest x-ray films. However, the distribution patterns of calcification are different and of diagnostic utility. Benign lesions tend to have calcium deposited in central, peripheral, concentric, “popcorn,” or homogeneous patterns, whereas eccentric patterns of calcification are more characteristic of malignancies (see later discussion and Fig. 44-1).

Among lung cancers, adenocarcinomas tend to be located peripherally; squamous and small cell cancers are usually more central in location. However, squamous cell cancers that are located peripherally tend to show cavitation.

Healed infectious granulomas used to account for the majority of solitary nodules, but with the increasing application of lowdose CT screening for lung cancer, the proportion of lesions due to malignancy is increasing. Of these, greater than 75% are primary lung cancers, and the remainder are metastatic lesions. Tumors of the breast, colon, and testicles are particularly prone to metastasize to the lung. Of the solitary pulmonary nodules that prove to be benign, 85% to 90% are granulomas; most are tuberculous, but in endemic areas, histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis are important considerations. Benign pulmonary tumors such as hamartomas account for about 5% of benign nodules. The remainder are bronchogenic cysts, hydatid cysts, pseudolymphomas, arteriovenous malformations, and bronchopulmonary sequestrations. Extrapulmonary lesions, such as skin lesions, moles, nipples, chest wall and rib lesions, and pleural plaques, may be confused with solitary lesions of lung parenchyma.