Evaluation of Disturbances in Pigmentation

Peter C. Schalock

Arthur J. Sober

Disturbances in pigmentation are conspicuous and common. Patients present with concerns about general darkening, brown spots, and depigmented areas. Pigmentary alterations may be manifestations of a genetic, endocrine, metabolic, nutritional, infectious, or neoplastic disorder. Physical and chemical factors also can be important because skin color can be altered by exposure to heat, solar and ionizing radiation, trauma, medications, heavy metals, and tattoos.

Hyperpigmentation

Pathophysiology

Pigmentary changes are caused by melanin being absent, decreased, increased, or abnormally placed or distributed. Hyperpigmentation may result from an increased rate of melanosome production, an increased number of melanosomes transferred to keratinocytes, or a greater size and melanization of melanosomes. Because of the Tyndall phenomenon, hyperpigmentation is perceived as blue when melanin is located deeply in the dermis.

The pathophysiologic mechanisms that produce hyperpigmentation through the melanocyte system include increased levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which has a melanocyte-stimulating action; ultraviolet radiation; and certain medications. Abnormal diffuse pigmentation may manifest as a change in pigment naturally present in skin or the expression of pigment in areas for the first time, such as the mucosal membranes, palmar creases, and intertriginous areas (body folds).

Hypomelanosis, or depigmentation, may result from the genetic loss of melanocytes, destruction by inflammation, or trauma. Inflammation may be secondary to infection or burns or associated with a variety of immunologically mediated diseases. Any damage to the skin may cause hypo- or hyperpigmentation, especially in darker-skinned individuals.

Clinical Presentation

Hyperpigmentation may be circumscribed (i.e., bounded, limited, or confined to a specific area) or diffuse.

Circumscribed Hyperpigmentation.

Circumscribed hyperpigmentation includes freckles (ephelides), lentigines (simple or solar), café au lait spots, dermal melanocytosis (formerly known as a “Mongolian spot”), nevus of Ota and Ito, Becker melanosis, melasma, and acanthosis nigricans.

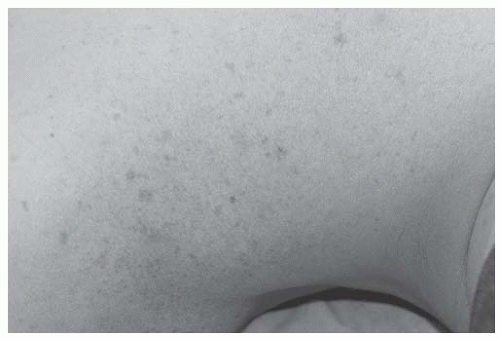

Freckles are small, macular lesions seen on areas exposed to the sun. Freckles may lighten in adults but darken after exposure to long-wave ultraviolet radiation. Lentigines are classified as solar or simple (Fig. 180-1). Both lentigines and freckles appear as macules, but lentigines are larger, are darker, and differ histologically from freckles. Simple lentigines are not associated with age or sun exposure and are clinically and histologically indistinguishable from solar lentigines, which often appear after the sixth decade on sun-exposed skin. Patients call solar lentigines “liver spots” and rarely realize that “liver” refers to the color of the lesion and not to its cause.

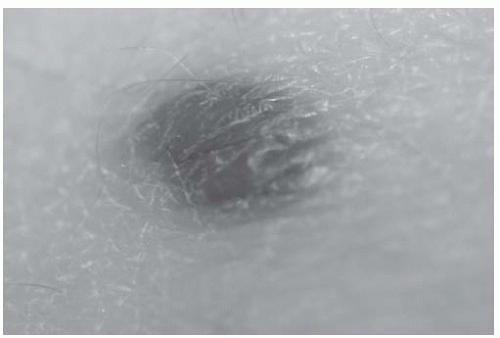

Café au lait spots are congenital or acquired, light to dark brown macules ranging in size from 1 to 20 cm. They can be round or oval with smooth or irregular borders. The presence of multiple lesions is associated most commonly with neurofibromatosis and McCune-Albright syndrome as well as Fanconi anemia and tuberous sclerosis. Dermal melanocytosis refers to round or oval, ill-defined, blue-hued patches on the sacrococcygeal area of infants usually of darker skin types. They represent benign dermal pigmentation that resolves over time. Nevus of Ito and Ota are most often unilateral, speckled blue-gray patches located on the shoulder and scapular skin or periorbital and facial skin, respectively. Becker melanosis (or Becker pigmented hairy nevus) (Fig. 180-2) is a hyperpigmented patch located on the chest, back, or shoulder with overlying hypertrichosis (hair growth) and, at times, an underlying smooth muscle hamartoma. A blue nevus is a blueblack lesion, either a macule or dome-shaped papule. These are usually located on the extremities (Fig. 180-3). Melanocytic nevi (“moles”) are also circumscribed, skin-colored to dark brown (depending on the individual’s skin) papules or macules.

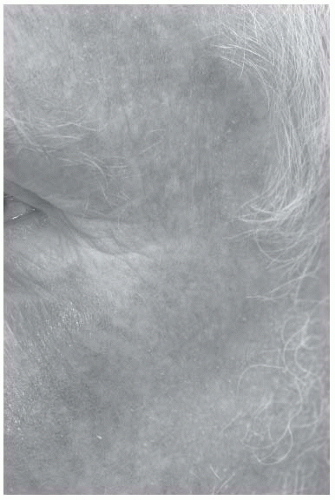

Melasma (Greek for “black spot”)/chloasma (pregnancyinduced melasma) is diffuse hyperpigmentation involving light brown to gray macules or patches that occur on the forehead, cheeks, and upper lip, usually in women. Sunlight exposure appears to be one of the most significant factors in developing and perpetuating the condition. In addition, hormones, especially estrogen and progesterone exposure during pregnancy, in birth control pills, or through hormone replacement therapy, substantially contribute to its development. Melasma is seen in up to 70% of pregnant women and 35% of women taking oral contraceptives and in men undergoing hormone therapy for

prostate cancer. On a related note, a physiologic darkening of the linea alba, pigmented nevi, nipples, and genitalia is caused by melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) and increased levels of estrogen and progesterone in pregnancy.

prostate cancer. On a related note, a physiologic darkening of the linea alba, pigmented nevi, nipples, and genitalia is caused by melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) and increased levels of estrogen and progesterone in pregnancy.

Acanthosis nigricans presents as “velvety” textured, hyperpigmented patches located around the neck, axillae, groin, and inframammary folds. Patients are often overweight and have an underlying endocrine disorder, such as diabetes mellitus or hyperandrogenism. The onset is usually slow and confined to skin folds and the back of the neck. In some cases, acanthosis nigricans can appear because of underlying malignancy, most often adenocarcinoma of the stomach or other gastrointestinal or genitourinary locations. Onset is rapid, often on the palms (tripe palms), and may be associated with eruptive seborrheic keratoses (sign of Leser-Trélat) and acrochordons. Other causes include systemic disease, medications, or genetics.

Figure 180-2 Becker nevus on the shoulder of a young man.In this case, he did not have hypertrichosis. |

Diffuse Hyperpigmentation.

Diffuse hyperpigmentation results from increased amounts of melanin in the epidermis. The color may be accentuated in sun-exposed areas, over pressure points or body folds, or in areas of trauma, such as new scars.

Addison disease is associated with increased amounts of MSH and ACTH as a compensatory feedback response to decreased adrenal cortisol levels. Hyperpigmentation on sun-exposed sites, the genitalia, and oral mucous membranes is common and may present before the progressive lethargy and hypotension are evident.

Metabolic diseases such as Wilson disease, von Gierke hemochromatosis, alkaptonuria, biliary cirrhosis, hyperthyroidism, and porphyria cutanea tarda may be accompanied by diffuse melanosis. On occasion, rheumatoid arthritis, Still disease, and scleroderma have been associated with hyperpigmentation.

Oral medications cause varying types of hyperpigmentation. Busulfan, minocycline, cyclophosphamide, clofazimine, 5-fluorouracil, psoralens, and zidovudine can produce diffuse melanosis, as can methotrexate, hydroxyurea, and topical nitrogen mustard. Chronic inorganic arsenic poisoning causes diffuse hyperpigmentation with normal or lighter skin areas scattered throughout, colorfully called “rain drops in the dust.”

Chlorpromazine, amiodarone (Fig. 180-4), and antimalarial drugs (i.e., hydroxychloroquine) tend to produce a bluish gray hyperpigmentation. Silver (argyria) and gold (chrysiasis), as well as bismuth and mercury, can accumulate in the skin and cause hyperpigmentation, depending on the dose given. Starvation (i.e., anorexia nervosa, bulimia, kwashiorkor, and marasmus), hepatic insufficiency, malabsorption syndromes, and lymphomas and melanomas may result in diffuse melanosis.

Focal Hyperpigmentation

Bleomycin can produce linear, flagellate hyperpigmentation. Exposure to a photosensitizer, such as oil of bergamot in perfumes and some hair preparations, can lead to photocontact dermatitis, which commonly appears on the neck or retroauricular skin; it is also referred to as berloque dermatitis. A similar compound (coumarin) in figs, parsnip, and citrus rinds causes inflammation and pigmentation in areas exposed to both the sensitizing chemical and the sun. A classic presentation is a bartender or vacationer with streaks of hyperpigmented skin on the extremities, corresponding to the circuitous path of oil and juice from citrus rind that arose on sun exposure after preparing mixed drinks.

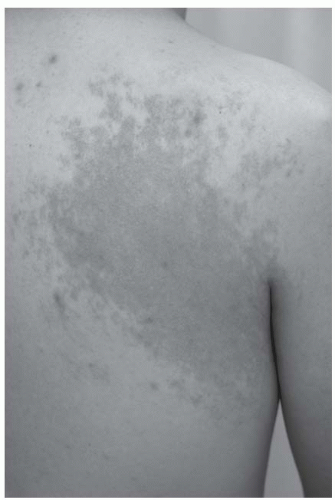

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is caused by a wide variety of etiologies, the common link being that the pigmentation changes follow skin inflammation (Fig. 180-5). Inflammatory disorders that

affect the dermal-epidermal junction (e.g., lichen planus, lupus erythematosus) may lead to pigmentary alterations. Photosensitizing agents present in meadow grasses, citrus fruits, and edible plants may cause an exaggerated sunburn. Hyperpigmentation follows the acute inflammatory phase. Tar, pitch, and oils can induce similar changes. Physical trauma, friction, and heat may also lead to postinflammatory pigmentary changes, as may inflammatory dermatoses that stimulate melanin formation. Pigment alteration (both hyper- and hypopigmentation) is also seen after cryogenic treatment (i.e., liquid nitrogen), chemical peels, and laser therapy. Patients with darker skin tones in particular must be informed of the risks inherent in any of these procedures.

affect the dermal-epidermal junction (e.g., lichen planus, lupus erythematosus) may lead to pigmentary alterations. Photosensitizing agents present in meadow grasses, citrus fruits, and edible plants may cause an exaggerated sunburn. Hyperpigmentation follows the acute inflammatory phase. Tar, pitch, and oils can induce similar changes. Physical trauma, friction, and heat may also lead to postinflammatory pigmentary changes, as may inflammatory dermatoses that stimulate melanin formation. Pigment alteration (both hyper- and hypopigmentation) is also seen after cryogenic treatment (i.e., liquid nitrogen), chemical peels, and laser therapy. Patients with darker skin tones in particular must be informed of the risks inherent in any of these procedures.

Other Discolorations.

Yellow discoloration of the skin is seen in carotenemia and jaundice; mucous membrane involvement leads to scleral icterus with jaundice. Carotenemia, due to an inability to convert ingested β-carotene to vitamin A (as in diabetes mellitus, anorexia, and hypothyroidism) or as a result of a high intake of carrots or other carotenoid-containing vegetables, can give the skin a yellow-orange tint. The accumulation of lycopene from excessive ingestion of tomatoes or papaya can also tint the skin. Quinacrine, phenazopyridines, and canthaxanthin can also cause a yellowish discoloration.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree