CHAPTER 166

Erysipelas, Cellulitis, Lymphangitis

Presentation

Erysipelas is a superficial cutaneous infection that commonly is found on the legs or face and generally does not have an inciting wound or skin lesion. It appears as a painful, bright fiery-red induration with raised, sharply demarcated borders, at times giving the skin a pitted appearance like an orange peel (peau d’orange) (Figure 166-1). Cellulitis, on the other hand, is deeper, involves the subcutaneous connective tissue, and has an indistinct advancing border. This deeper infection is characterized by pain and tenderness and by warmth and edema, which give the skin a light red or pink appearance (Figure 166-2). Cellulitis can occur on any part of the body but is most commonly found on the legs, face, feet, and hands. Lymphangitis has minimal induration and an unmistakable erythematous linear pattern ascending along lymphatic channels (Figure 166-3).

Figure 166-1 Erysipelas on the face (A); erysipelas of the leg (B). (Adapted from White G, Cox N: Diseases of the skin, ed 2. St Louis, 2006, Mosby.)

Figure 166-2 Cellulitis with tender erythema, swelling, and warmth of the patient’s left leg. (Adapted from Knoop K: Atlas of emergency medicine, ed 2. New York, 2002, McGraw-Hill.)

Figure 166-3 Lymphangitis. (From Knoop K: Atlas of emergency medicine, ed 2. New York, 2002, McGraw-Hill.)

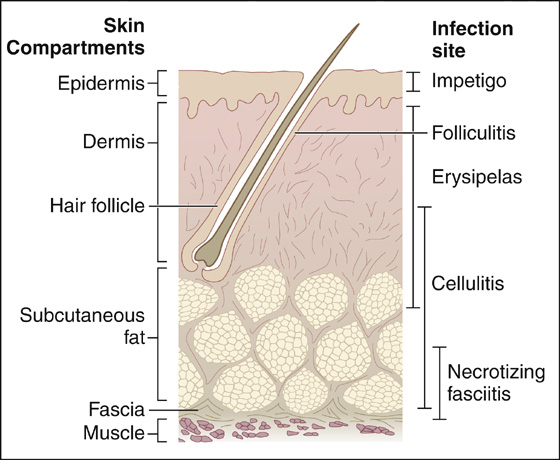

These relatively superficial skin infections (Figure 166-4) are often preceded by minor trauma, such as an abrasion or the presence of a foreign body, and are most common in patients who have predisposing factors, such as diabetes, drug addiction, alcoholism, immunosuppression, arterial or venous insufficiency, and lymphatic drainage obstruction. They may be associated with an abscess or other dermatologic abnormality, such as tinea pedis, impetigo, or folliculitis. Often they have no clear-cut origin. With any of these skin infections, the patient may have tender lymphadenopathy proximal to the site of infection and may or may not have signs of systemic toxicity (fever, chills, rigors, and listlessness).

Figure 166-4 Cutaneous anatomy and sites of infection. (Adapted from Gorbach SL: Infectious diseases, ed 3. Philadelphia, 2003, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.)

What To Do:

Perform a careful history and physical examination to determine if there are any underlying factors that would predispose the patient to such an infection. History of a previous injury, suspicion of a retained foreign body, or knowledge of previous infections may help clarify a possible cause. Underlying illness, such as diabetes, renal failure, chronic dependent edema, immunosuppression, or postoperative lymphedema, will give clues to an underlying predisposition to developing these infections and the need for hospitalization.

Perform a careful history and physical examination to determine if there are any underlying factors that would predispose the patient to such an infection. History of a previous injury, suspicion of a retained foreign body, or knowledge of previous infections may help clarify a possible cause. Underlying illness, such as diabetes, renal failure, chronic dependent edema, immunosuppression, or postoperative lymphedema, will give clues to an underlying predisposition to developing these infections and the need for hospitalization.

Look for a possible source of infection and remove it. Débride and cleanse any wound, remove any foreign body, and drain any abscess.

Look for a possible source of infection and remove it. Débride and cleanse any wound, remove any foreign body, and drain any abscess.

When the patient is very sick with high fever or severe pain, or the area of skin involvement is greater than 50% of limb or torso or greater than 10% of total body surface, obtain medical consultation, if needed, and prepare the patient for hospitalization and IV antibiotics. Other indications for hospitalization include a rapidly advancing edge of cellulitis that exceeds 5 cm per hour or coexisting morbidity, as noted. Obtain a complete blood count (CBC) and blood cultures, and consider obtaining radiographs to look for gas-forming organisms. Air in the soft tissues may represent necrotizing fasciitis, and rapid surgical débridement is indicated. Obtain cultures from any associated wounds. If there is no wound to culture in these complicated cases, it is reasonable to attempt a needle aspiration of fluid from the leading edge of the involved area. These fluid cultures, however, are often unsuccessful in establishing a bacteriologic diagnosis. Hospitalization should also be strongly considered for central facial erysipelas or cellulitis, a deep infection of the hand, or failure to respond after 72 hours of oral antibiotic therapy.

When the patient is very sick with high fever or severe pain, or the area of skin involvement is greater than 50% of limb or torso or greater than 10% of total body surface, obtain medical consultation, if needed, and prepare the patient for hospitalization and IV antibiotics. Other indications for hospitalization include a rapidly advancing edge of cellulitis that exceeds 5 cm per hour or coexisting morbidity, as noted. Obtain a complete blood count (CBC) and blood cultures, and consider obtaining radiographs to look for gas-forming organisms. Air in the soft tissues may represent necrotizing fasciitis, and rapid surgical débridement is indicated. Obtain cultures from any associated wounds. If there is no wound to culture in these complicated cases, it is reasonable to attempt a needle aspiration of fluid from the leading edge of the involved area. These fluid cultures, however, are often unsuccessful in establishing a bacteriologic diagnosis. Hospitalization should also be strongly considered for central facial erysipelas or cellulitis, a deep infection of the hand, or failure to respond after 72 hours of oral antibiotic therapy.

If there is little or no fever and the patient is nontoxic and has no significant comorbidity, it is appropriate to treat the patient on an outpatient basis. For other than mild infections, it may be most effective to give an initial IV dose of nafcillin (Unipen), 1 to 2 g, or cefazolin (Ancef), 1 to 2 g; or, if the patient is highly allergic to penicillin, vancomycin (Vancocin), 1 to 2 g. Then prescribe dicloxacillin (Dynapen), 500 mg qid × 10 to 14 days; cephalexin (Keflex), 500 mg tid × 10 to 14 days; cefadroxil (Duricef), 1 g qd × 10 to 14 days; or, in penicillin-allergic individuals, azithromycin (Zithromax), 500 mg, then 250 mg qd × 4 days.

If there is little or no fever and the patient is nontoxic and has no significant comorbidity, it is appropriate to treat the patient on an outpatient basis. For other than mild infections, it may be most effective to give an initial IV dose of nafcillin (Unipen), 1 to 2 g, or cefazolin (Ancef), 1 to 2 g; or, if the patient is highly allergic to penicillin, vancomycin (Vancocin), 1 to 2 g. Then prescribe dicloxacillin (Dynapen), 500 mg qid × 10 to 14 days; cephalexin (Keflex), 500 mg tid × 10 to 14 days; cefadroxil (Duricef), 1 g qd × 10 to 14 days; or, in penicillin-allergic individuals, azithromycin (Zithromax), 500 mg, then 250 mg qd × 4 days.

Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) has become a common source of infection. Although it more typically forms abscesses, cellulitis is also common. Obtaining cultures is even more important, and opening any pocket of purulence is essential to successful treatment. Antibiotic coverage should consist of vancomycin, 1 to 2 g IV, or clindamycin (Cleocin), 900 mg IV. In the most worrisome infections, order linezolid (Zyvox), 600 mg IV (highly expensive), followed by a prescription for clindamycin (Cleocin), 300 mg q6h × 10 to 14 days, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim DS), 160 TMP q12h × 10 to 14 days (alone or in combination with rifampin, 300 mg q12h), or linezolid, 600 mg q12h × 10 to 14 days (highly expensive). Oral antibiotics alone may be used in less worrisome infections.

Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) has become a common source of infection. Although it more typically forms abscesses, cellulitis is also common. Obtaining cultures is even more important, and opening any pocket of purulence is essential to successful treatment. Antibiotic coverage should consist of vancomycin, 1 to 2 g IV, or clindamycin (Cleocin), 900 mg IV. In the most worrisome infections, order linezolid (Zyvox), 600 mg IV (highly expensive), followed by a prescription for clindamycin (Cleocin), 300 mg q6h × 10 to 14 days, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim DS), 160 TMP q12h × 10 to 14 days (alone or in combination with rifampin, 300 mg q12h), or linezolid, 600 mg q12h × 10 to 14 days (highly expensive). Oral antibiotics alone may be used in less worrisome infections.

Provide tetanus prophylaxis as indicated, and prescribe analgesics for pain as needed.

Provide tetanus prophylaxis as indicated, and prescribe analgesics for pain as needed.

Always outline the leading edges of the infection with a pen or marker so that the patient and follow-up clinician can monitor the effectiveness of the treatment.

Always outline the leading edges of the infection with a pen or marker so that the patient and follow-up clinician can monitor the effectiveness of the treatment.

Instruct the patient to keep the infected part at rest and elevated and to use intermittent warm (some experts recommend cool) moist compresses.

Instruct the patient to keep the infected part at rest and elevated and to use intermittent warm (some experts recommend cool) moist compresses.

Follow up within 24 to 48 hours to ensure that the therapy has been adequate. Infections still worsening after 24 to 48 hours of outpatient treatment will either need a change in antibiotic therapy or require hospital admission for better immobilization, elevation, and IV antibiotics.

Follow up within 24 to 48 hours to ensure that the therapy has been adequate. Infections still worsening after 24 to 48 hours of outpatient treatment will either need a change in antibiotic therapy or require hospital admission for better immobilization, elevation, and IV antibiotics.

What Not To Do:

Do not obtain blood cultures or try to aspirate the border of a lesion for bacterial culture in uncomplicated cases. The yield is very low, and it produces unnecessary pain and expense.

Do not obtain blood cultures or try to aspirate the border of a lesion for bacterial culture in uncomplicated cases. The yield is very low, and it produces unnecessary pain and expense.

Do not overlook a case of necrotizing fasciitis, myonecrosis, or pyomyositis. These patients generally have comorbid conditions, systemic toxicity, and, in the case of pyomyositis, a prolonged course (see Discussion).

Do not overlook a case of necrotizing fasciitis, myonecrosis, or pyomyositis. These patients generally have comorbid conditions, systemic toxicity, and, in the case of pyomyositis, a prolonged course (see Discussion).

Discussion

Erysipelas (known in the Middle Ages as St. Anthony’s Fire) is a rapidly progressing, erythematous, indurated, painful, and sharply demarcated area of superficial skin infection that is usually caused by Streptococcus pyogenes. Other causes include Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA) and Streptococcus pneumoniae. The initial site of entry is often trivial or not apparent. Systemic symptoms, such as chills and fever, are common. Predisposing factors include venous stasis, diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, and chronic lymphatic obstruction. Erysipelas may progress to cellulitis.

Cellulitis is a deeper skin infection extending through the subcutaneous tissue. It appears as a painful, tender, erythematous, warm area that spreads along indistinct borders. Fever, chills, rigors, and sweats are frequent. There is often an extension via the lymphatic system, producing lymphangitis (once referred to as blood poisoning). Causative organisms include group A beta-hemolytic streptococci, S. aureus (including MRSA), and Streptococcus pyogenes. Predisposing factors are similar to erysipelas, but also look for tinea pedis with fissures, which can serve as a common portal of entry.

All of these infections are typically diagnosed by clinical presentation and treated empirically. The recent increase in CA-MRSA infections must influence the clinician to maintain a cautious skepticism regarding the use of a traditional antibiotic regimen for treatment of erysipelas, cellulitis, and lymphangitis. Penicillinase-resistant penicillins and cephalosporins would not be expected to be effective against these microorganisms. Clindamycin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are more effective choices currently, but these choices will certainly change in the future.

Alternative conditions exist that can mimic uncomplicated cutaneous infections and may not be apparent until follow-up. These may include abscess, herpes zoster, septic bursitis, gout, and septic arthritis.

Three conditions that should never be confused with uncomplicated cellulitis are necrotizing fasciitis, myonecrosis, and pyomyositis.

Necrotizing fasciitis is a deep-seated polymicrobial infection that results in the progressive destruction of fascia and fat. It most commonly is found in patients with impaired circulation, immune compromise, or in intravenous drug users. When this infection is caused by group A streptococci, it is often referred to as “flesh-eating bacteria” by the press. These patients rapidly become very ill with signs and symptoms of systemic toxicity. The affected area (most often the extremities, particularly the legs) is initially erythematous, swollen, hot, shiny, exquisitely tender, and painful. Skin changes progress from red-purple to patches of blue-gray, then to bullae (with clear fluid) associated with marked swelling and edema. These patients develop anesthesia over the affected area, the result of destruction of superficial nerves caused by thrombosis of small blood vessels. It is essential to distinguish necrotizing fasciitis from the less dangerous cellulitis or erysipelas. Urgent surgical débridement and antibiotic therapy are required if the patient is to survive. The presence of marked systemic toxicity, severe pain, numb skin surface, color changes (red to blue-gray), tendon or nerve impairment, crepitation, and bullae formation point to necrotizing fasciitis.

Myonecrosis or gas gangrene is a pure Clostridium perfringens infection characterized by gas in a gangrenous muscle group. (Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. can also produce gas under anaerobic conditions.) Currently, this is an unusual infection but remains devastating and also requires rapid surgical intervention, IV antibiotics, and hyperbaric oxygen, if available. Pain is the earliest and most common symptom and is accompanied by fever and tachycardia. The patient appears pale, sweaty, and sick. Edema and tenderness may be the only local symptoms. The wound discharge, if present, typically is serosanguineous and dirty and has a foul odor.

Pyomyositis is often referred to as “tropical pyomyositis,” because it is endemic in the tropics. These patients will also often have a predisposing condition or comorbidity, such as diabetes mellitus, alcoholic liver disease, concurrent corticosteroid therapy, or immunosuppression. This is an infection of skeletal muscle, usually caused by S. aureus. One or more muscles may be affected, most frequently the thigh and buttocks. The muscles initially feel achy or crampy, and examination reveals a woody, deep induration of the muscle belly. This is usually a slowly progressive disease; if untreated, within 2 weeks fluctuation, erythema, and then boggy swelling will develop. Tenderness is minimal initially, but fever and marked muscle tenderness develop as the infection progresses. MRI shows enlargement of the involved muscles along with any fluid collection. Surgical drainage is essential for treatment, along with empirical antibiotic therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree