Fig. 1.1

Forrest classification can be summarized as grade: (Aa) Arterial hemorrhage (“spurting”). (Ab) Diffuse hemorrhage (“oozing”). (Ba) Non-bleeding visible vessel. (Bb) Adherent clot. (Bc) Flat pigmented spot. (C) Ulcer without recent stigmata of bleeding (“clean base”). From Seung Young Kim, Jong Jin Hyun, Sung Woo Jung, and Sang Woo Lee, Management of Non-Variceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding, Clin Endosc. 2012 September; 45(3): 220–223

Controversy exists regarding how aggressive the endoscopist should be in attempting to dislodge an adherent clot from a nonbleeding ulcer.

Esophageal Varices Associated with Portal Hypertension (Fig. 1.2)

Early endoscopy with confirmation of a variceal source of bleeding and therapeutic banding of bleeding varices should be carried out in those institutions with skilled endoscopic support. Smaller institutions with limited resources should consider early transfer to a tertiary center with advanced endoscopic and radiologic support, unlimited resources, and capabilities for emergent portal-systemic shunting (TIPS). Specific measures can be utilized to better stabilize the patient whether the patient is treated locally or while arrangements are being made for transfer to a tertiary center.

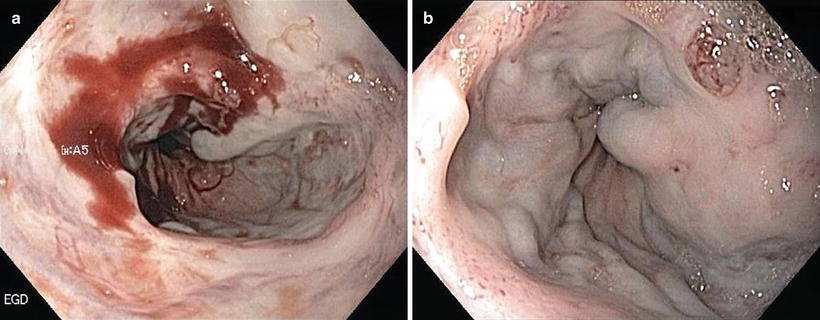

Fig. 1.2

Esophageal varices

Specific measures include:

Intravenous fluid resuscitation.

Early endotracheal intubation to prevent aspiration and respiratory compromise.

Blood component therapy to correct anemia and coagulopathy.

Octreotide infusion (50 μg bolus then 50 μg/h infusion) to increase splanchnic vascular resistance and decrease bleeding. Octreotide has been shown to be equally as effective as vasopressin in reducing or stopping variceal bleeding and avoids the cardiac and mesenteric vascular complications of vasopressin.

Mechanical compression of bleeding varices with a Sengstaken–Blakemore tube or one of its variants.

Mallory–Weiss Tears (Fig. 1.3)

Mallory–Weiss tears are lacerations in the region of the esophago-gastric junction that account for 5–15 % of cases of UGIB. Vomiting is the usual cause for the tear. Bleeding is self-limited in 80–90 % of cases with a very low incidence of rebleeding. Supportive therapy is usually all that is indicated although if necessary, endoscopic therapy with electrotherapy, heater probes, clipping, and injections are all effective (Fig. 1.4).

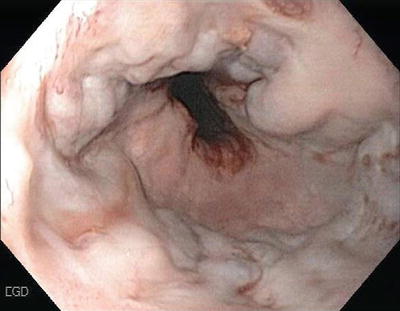

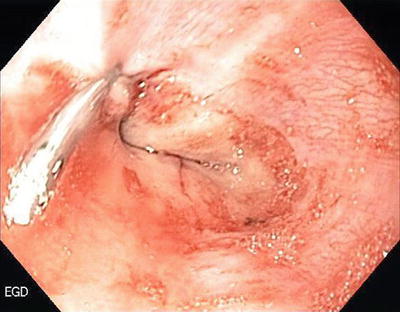

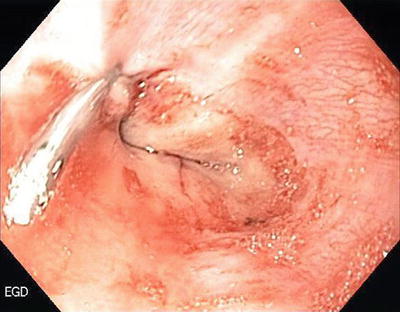

Fig. 1.3

Mallory–Weiss tear at GE junction

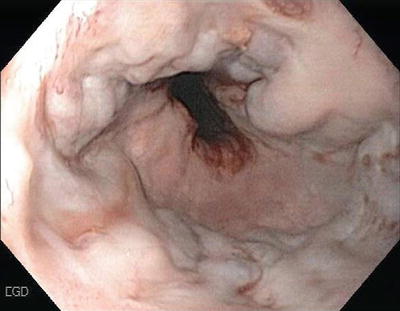

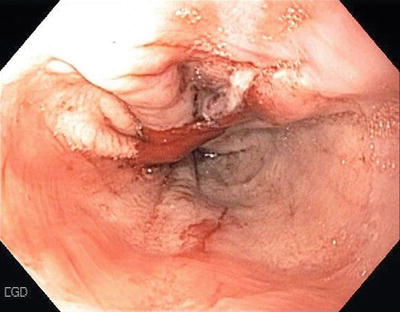

Fig. 1.4

Mallory–Weiss tear treated with injection and clipping

Dieulafoy’s Lesion

This lesion was first described in 1896. It consists of an abnormally large submucosal artery protruding through a minute mucosal defect. Dieulafoy’s lesion can cause significant bleeding and are often difficult to diagnose especially if there is not active bleeding present during endoscopy. The lesions occur twice as often in men than in women and usually in patients with multiple comorbidities. The lesions are found in the upper part of the stomach in 75 % of cases usually on the lesser curve within 6 cm of the GE junction. Combination endoscopic therapy (injection/clipping or injection/coagulation) is exceedingly effective in arresting the hemorrhage and preventing rebleeding when the lesion is identified and treated (Fig. 1.5).

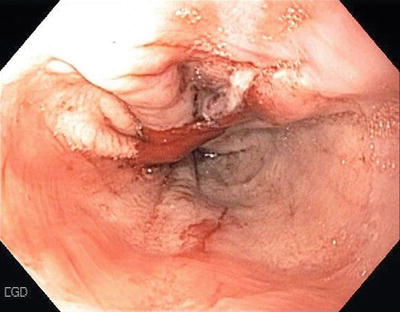

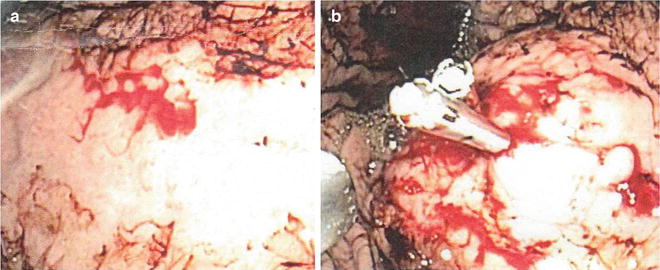

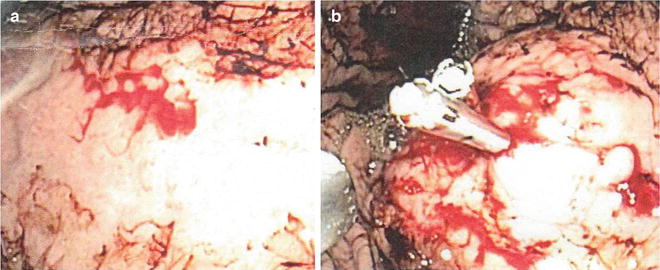

Fig. 1.5

Bleeding Dieulafoy’s lesion (a) with injection/clip application (b)

Congestive Gastropathy

This is a condition related to portal hypertension that causes chronic blood loss in cirrhotic patients. It mimics gastritis on endoscopy and microscopically reveals dilated submucosal veins and vascular ectasia in the muscle layer. The primary therapy is reduction of portal venous pressure and not endoscopic therapy.

Vascular Conditions

Angiodysplasia accounts for 5–7 % of UGIB. It can be associated with advanced age, chronic renal failure, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, and prior radiation therapy. Individual lesions can be treated with mechanical clipping or ablation techniques but patients with multiple diffuse lesions are problematic from an endoscopic approach.

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVES) or “watermelon stomach” is an uncommon vascular malformation of unknown etiology. The lesion presents endoscopically as wide stripes of erythematous friable mucosa in the gastric antrum resembling a watermelon rind (Fig. 1.6). Argon plasma coagulation (APC) and radiofrequency ablation have been described to treat this condition.

Fig. 1.6

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVES)

Aorto-Enteric Fistula

Fistulae between the aorta and bowel can occur after Dacron graft replacement of the aorta. Atherosclerotic plaque or mycotic aneurysm can less commonly result in a fistula. The lesion involves the third or fourth portion of the duodenum and in many cases the graft can be visualized protruding through the back wall of the duodenum (Fig. 1.7). A CT scan with IV contrast can also make the diagnosis. Patients have an initial “herald bleed” which can abate on its own to be followed by a massive exsanguinating event hours, days, or weeks later. Endoscopy can make the diagnosis but there is no role for endoscopic therapy for this life-threatening condition. Even with immediate transfer and surgical therapy there is a very significant rate of morbidity and mortality with this condition.

Fig. 1.7

Aorto-enteric fistula, endoscopic view. White arrow—duodenal lumen; black arrow—aorto-enteric fistula

Neoplasms

Malignant lesions of the upper GI tract are uncommon causes of UGIB and usually self-limited. Endoscopy plays a limited role in therapy.

Anastomotic Ulcers (Fig. 1.8)

Anastomotic ulcers, also termed marginal or stomal ulcers, occur in 0.6–16 % of bariatric patients treated with laparoscopic rou-en-y gastric bypass. Nonsurgical approaches are successful in healing the lesions in 68–88 % of the cases. Up to 1/3 of patients may ultimately need surgical revision and even in these re-operated cases up to 10 % may have a recurrence. Bleeding lesions are treated in the same fashion as peptic ulcers.

Fig. 1.8

Anastomotic ulcer

Operative Technique

A plethora of injections, devices, and tools are available to the endoscopist treating patients with UGIB. The availability of certain therapies in smaller institutions may be limited by financial constraints but most cases of UGIB can be treated with many different single and combination modalities. Each endoscopist must become comfortable and familiar with the available devices in their individual institution. Obviously, the rural surgical endoscopist must be knowledgeable and confident in their ability to perform standard open surgical therapy to control hemorrhage when endoscopic therapy fails to stabilize the patient. The timing, surgical approach, and resources required should be considered even as the initial endoscopy is being carried out.

A partial list of available modalities includes:

Injection therapy:

Normal or concentrated saline injection

Epinephrine (adrenaline)

Sclerosants (ethanol, ethanolamine, polidocanal)

Thrombin

Fibrin

Cyanoacrylate glues

Cautery devices:

Heat probes

Neodymium-yttrium aluminum garnet lasers (YAG)

Argon plasma coagulation (APC)

Electrocautery probes (BICAP, GOLD Probe)

Radiofrequency ablation devices

Mechanical therapy:

Endoscopic clips

Endoscopic Band Ligation devices

Future modalities undergoing clinical testing

Endoscopic nanopowder spray

Endoscopic suture methods

Therapeutic Endoscopic Techniques

Injection Therapy

Saline With/Without Epinephrine

Injections with concentrated saline solutions containing diluted epinephrine are widely utilized because of its ease of use and beneficial effects. A standard retractable 25-gauge sclerotherapy needle is used to inject a solution of 1:10,000 epinephrine and saline into and around the bleeding point. Injection of 1.0 mL aliquots into the submucosal space promotes hemostasis by local tamponade, by promoting vasospasm and causing thrombosis (Fig. 1.9). Rebleeding occurs in 15–20 % of lesions treated by injection alone. Application of a second hemostatic technique (ablative or mechanical), in addition to injection, can provide a more permanent hemostasis. Limiting the volume of epinephrine solution to 12 mL or less reduces potential toxic cardiac effects including angina, tachycardia, arrhythmias, and hypertension. To further decrease the cardiac risks in at-risk patients, concentrated saline without epinephrine can also be effective.