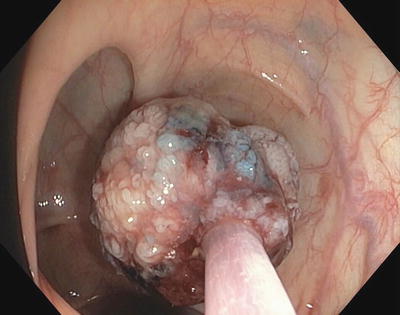

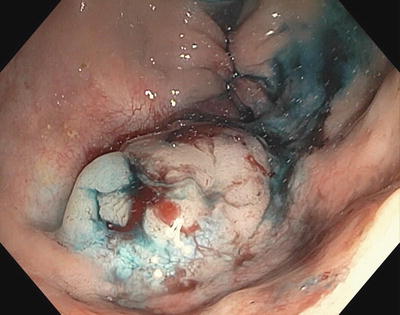

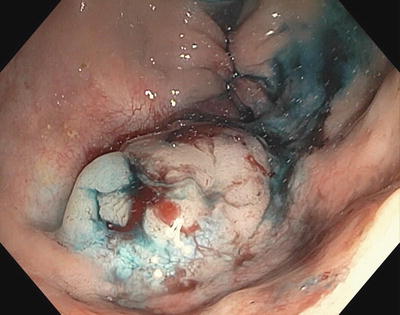

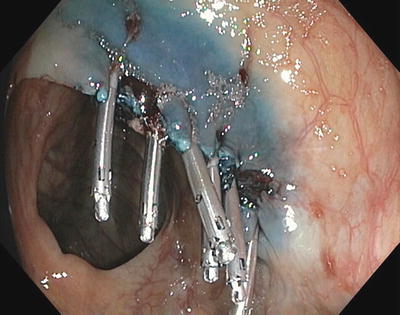

Fig. 3.1

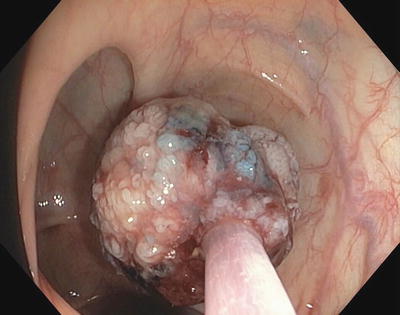

Polyp encountered at 3 o’clock

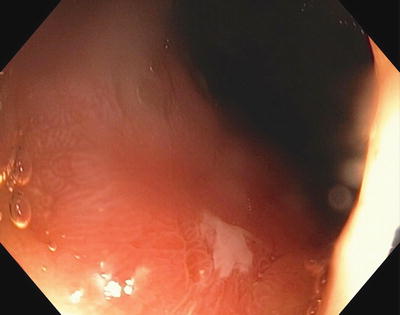

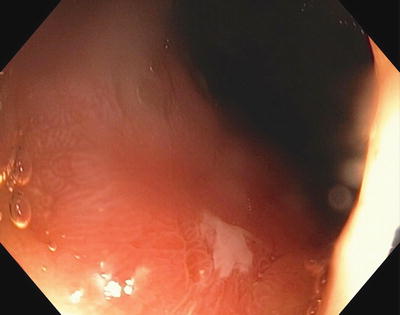

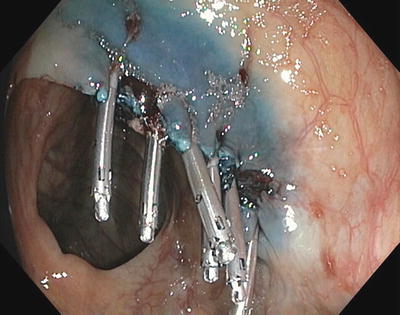

Fig. 3.2

Polyp positioned at 5 o’clock

Once the lesion is determined to be resectable and is properly positioned, determination should be made about the endoscopist’s ability to remove the lesion en bloc or piecemeal. The benefit of an en bloc resection is that the anatomic margins of the lesion may be preserved allowing the endoscopist and pathologist to better determine the completeness of the resection. However, there may be a slightly higher risk of perforation and bleeding, as well as an increase in difficulty retrieving larger polyps after en bloc polypectomy. Piecemeal resection allows for improved ease of polyp retrieval and decreased risk of perforation, but has also been shown to have up to a 55 % rate of early recurrence or residual polyp. In most cases the residual polyp can be completely removed with subsequent endoscopic treatment, but all polyps removed piecemeal should be re-examined in 2–6 months to ensure complete resection has been achieved.

Advanced polyps can be removed by cold scare, snare cautery, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). If a cold snare is used, it is often done in attempting a piecemeal resection, cutting through smaller sections of tissue than can be achieved with snare cautery. Due to the large size often encountered with difficult polyps, thermal energy is frequently used to assist with cutting. The use of thermal energy may increase the risk of bleeding and mural thermal injury.

EMR is generally defined as the removal of a flat or sessile polyp confined to the mucosa or submucosa, usually for lesions >2 cm in size. Injection-assisted, cap-assisted and ligation-assisted techniques have been described to perform EMR. EMR is the most widely accepted method of performing advanced polypectomy. ESD involves dissecting the polyp off the submucosal space and is a more meticulous, time-consuming and technically challenging method of performing advanced polypectomy.

EMR is currently the preferred method of performing polypectomy in large or difficult polyps. The benefit of this technique is to raise the apex of the polyp to better allow visualization and ease of capture with a snare, to predict deeper polyp invasion, and to decrease the risk of bleeding and perforation. In one study EMR led to upstaging of polyps to high grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma in up to 44 % of cases. With the injection-assisted technique, fluid is injected into the submucosal space, thus creating a cushion between the polyp within the mucosa and the deeper muscularis propria. The cap-assisted technique is performed by placing a plastic cap over the tip of the endoscope, seating a snare into the distal tip of the cap, and then suctioning the tissue into the cap. When using this technique, the mucosa and submucosa, but not the muscularis propria are suctioned into the cap. The snare is then closed around the base of the tissue and snare cautery polypectomy is performed. The ligation-assisted technique is similar to the cap-assisted technique, but rather than a dedicated cap device, a band ligation device is used. The polyp is suctioned into the band ligation cap and a band is placed at the base of the lesion. The snare is placed either distal or proximal to the band, and snare cautery polypectomy is performed. All three techniques require similar technical skills, including performing a submucosal injection and a snare polypectomy.

The type of fluid used for submucosal injection may vary some. Osmotic agents such as hyaluronic acid, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, glycerol, and fibrinogen solution generally remain in the submucosal space for a greater length of time, making these favorable agents to use in cases of prolonged attempts at capturing the lesion with the snare. However, these osmotic agents are expensive and not readily available in most endoscopy units, and some have also been shown to cause tissue damage. Autologous blood injections last up to seven times longer than normal saline and do not hinder visualization. In most institutions normal saline is used because of its low cost and availability. Another technique is to mix 1 mL of 1:10,000 epinephrine and 1 mL of indigo carmine or methylene blue with 8 mL of 0.9 % NS. This mixture may better aid in visualizing the resected borders of the lesion and may decrease the risk of immediate bleeding. The submucosal injection can be performed by placing the lesion at the 5–6 o’clock position and approaching the lesion with an injection needle from a 20–30° angle (Fig. 3.3). A steeper approach runs the risk of advancing the needle through the serosa and injecting fluid into the abdomen. Starting in the proximal aspect or the portion of the polyp farthest away from the scope, 3–10 mL of fluid is injected in the submucosal space, which should aid to bring the polyp into view.

Fig. 3.3

Injection needle piercing the mucosa at the 20–30° angle. Start proximal and end distal

Once a submucosal injection has been performed and the polyp is successfully lifted, the injection needle may be withdrawn from the scope and replaced with a snare (Fig. 3.4). Saline will diffuse out of the submucosal space within minutes, so deliberate positioning of the snare is crucial (Fig. 3.5). If the lesion cannot be grasped with the snare prior to diffusion of the submucosal injection, repeat injection may be needed. The iSnare™ system contains both an injection needle and snare in one device, allowing for a more rapid placement of the snare after injection or repeated injections without removal of the device. Once the lesion is grasped firmly with the snare it should be retracted away from the wall of the colon towards the lumen, pulling the submucosa away from the muscularis and serosa (Figs. 3.6 and 3.7). A short burst of coagulation is applied as the snare is slowly closed to complete the cut through the retracted tissue. Thermal settings vary and many devices have preset levels for specific regions of the bowel, therefore the endoscopist needs to become familiar with these settings to avoid too little energy leading to a failure to cut thicker tissue, or too much energy leading to thermal injury to deeper colonic tissue. In general the coagulation mode is adequate to perform the initial resection with less of a risk for thermal injury. The cutting mode should be reserved for cases when the residual stalk is stuck to the snare (Fig. 3.8).

Fig. 3.4

Lift complete without tethered areas

Fig. 3.5

Snare positioned around polyp while lifted

Fig. 3.6

Snare closed around polyp

Fig. 3.7

Piecemeal excision of large right sided polyp. Snare is closed around polyp and preparing to cut through the polyp with cautery

Fig. 3.8

Excised polyp after saline and methylene blue submucosal lift demonstrating good staining of submucosal tissues

Appropriate snare selection depends on the size, location, and thickness of the polyp. Snares vary in size (from 1 to 3 cm), shape (from oval to hexagonal to round), and stiffness. No one snare routinely performs better than another, but having a few options to choose from may improve the ability to perform a complete polyp resection.

Once the polyp has been resected, retrieval of the entire polyp including all of the resected pieces of the polyp is critical to ruling out malignancy and assessing margins of resection. Suction ports vary in diameter from 3.2 to 3.8 mm. The polyp can then be collected in a tissue trap or by placing a gauze pad or nylon mesh between the suction nipple of the colonoscopy and the suction tubing. Tissue specimens larger than the diameter of the suction port can be compressed and pulled through the port, but typically polyps larger than 6–7 mm do not fit through suction port, and an alternate method of retrieval is needed. Although larger polyps can be cut into smaller pieces and suctioned through the scope, this further disrupts tissue, which may hinder pathologic analysis and prompt unnecessary surgery. The polyp can be held to the tip of the endoscope with suction and dragged out of the colon. This method is often unsuccessful, especially when maneuvering the tissue through the folds in the sigmoid colon. A variety of nets and baskets have been developed to retrieve larger pieces of tissue. The Roth Net™ is one of the more common retrieval devices, but its major limitation is difficulty in capturing multiple polyps or polyp fragments at one pass. Another company has recently developed the Twister® Plus rotatable retrieval device that comes in either a 22 or 26 mm loop diameter, and can be used to scoop up polyp fragments. Once captured by a net or basket, the tissue can be pushed 1–2 cm proximal to the tip of the endoscope to allow for continued visualization of the colon as the scope and tissue capture device is withdrawn completely. Some authors suggest the use of an overtube when removing multiple tissue fragments through a challenging sigmoid colon, to facilitate repeated cecal intubations.

Potential Pitfalls

In some instances a small amount of residual polyp may be difficult to resect, or cauterized tissue may preclude determination of the completeness of resection. In these cases application of thermal destruction of tissue, often by way of argon plasma coagulation (APC), may be used. This method has been shown to reduce the risk of recurrent polyp (Fig. 3.9).

Fig. 3.9

Argon plasma coagulation after lift and hot snare excision

Colonic mucosa heals quite well, which can make determination of the prior site of polypectomy difficult to identify on future colonoscopy (Figs. 3.10 and 3.11). Most studies report at least a 17 % rate of residual or recurrent polyp after piecemeal resection. For this reason, a tattoo should be made at the site of the polypectomy, particularly when piecemeal resection is performed. Data from the British Bowel Cancer Screening Programme suggest that due to an increased risk of dysplasia or cancer seen in polyps that are >1 cm in size, all polyps >1 cm should be tattooed. This is done by injecting a permanent ink (such as carbon black or India ink) into the submucosal space adjacent to the site of polypectomy. Indigo carmine, methylene blue, and other solutions have been used, but due to their rapid rate of resorption they are not effective agents for tattooing. Once again, care should be taken to approach the mucosa at a shallow angle so that the needle is in the submucosal space and not the serosa. Tattoos can be placed proximal and distal or in four quadrants around the lesion.

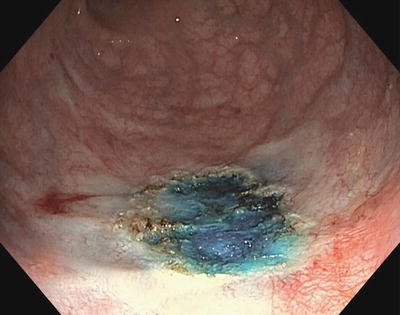

Fig. 3.10

Original polyp with saline and methylene blue submucosal lift

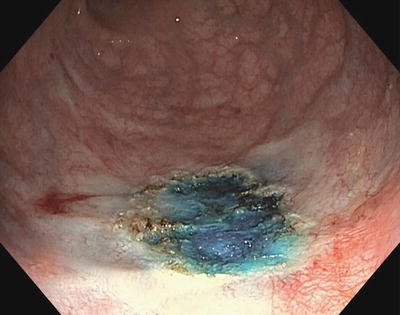

Fig. 3.11

Residual scar after only 1 month

Occasionally, resected polyps can be lost in deep pools of fluid or behind folds. Factors associated with failed polyp retrieval are small polyp size, sessile polyps, cold snare polypectomy, and proximal colon location. Adequate polyp retrieval should occur >90 % of the time per guidelines from the Bowel Cancer Screening Program. The easiest method of polyp retrieval is through the suction port of the colonoscope.

Common Complications

Complication rates for EMR vary, with rates of bleeding in 1–45 % (10 % in larger series), delayed bleeding in 13.9 %, and perforation in 0.3–0.5 %.

Postpolypectomy bleeding (PPB) rates vary greatly depending on several factors, but occurs 1–45 % (10 % in larger series), with delayed bleeding occurring in 1–13.9 % of cases. This is the leading major complication following colonoscopic polypectomy. Therapeutic endoscopic options for treatment of PPB are divided into three categories: compression, injection, and thermal coagulation. Endovascular embolization and operative resection remain options for patients who are unstable or fail endoscopic therapies. Due to the nature of this chapter the discussion will be limited to endoscopic therapies.

Compression techniques include re-snaring the stalk of the polypectomy site in cases of pedunculated polyps, or use of one of the endoscopic clip applicators for pedunculated or sessile polypectomy sites (Fig. 3.12). Newer endoscopic clipping devices contain a grasper that can grab both sides of the cut edges of the mucosa and once approximated, a clip device is applied from an endocap. Any of these therapies can be used together as the endoscopist needs to promote hemostasis. Injection therapy with one milliliter of 1:10,000 epinephrine solution is performed as described above for submucosal therapy and is placed at and around the site(s) of bleeding. Thermal hemostasis is achieved with either contact or noncontact therapy. Contact thermal treatment can be by either bipolar coagulation or a heater probe and is applied directly to the site of bleeding, using pressure and heat to coagulate the bleeding. Noncontact therapy is done by laser or argon plasma to produce coagulation from a short distance away, and does not have to be pulled off the coagulum at the end of the procedure.

Fig. 3.12

Mucosal defect closed with endoscopic clips after PPB

Although delayed bleeding usually occurs within 7–10 days, PPB has been reported from 0 to 29 days following therapy. Postpolypectomy bleeding is usually self-limited and over 70 % of cases resolve with only resuscitation and supportive care.

Risk factors for PPB include removal of large polyps (greater than 1 cm in diameter), age over 65 years, cardiovascular or chronic renal disease, platelet dysfunction, and coagulopathy. Multiple studies have tried to identify techniques to reduce the risk of postpolypectomy bleeding, and it is unclear whether the type of electrical current (blended vs. cutting ± APC), placement of prophylactic endoscopic clips, or use of an endoloop clearly decreases the risk of postpolypectomy bleeding, but they have all shown to be effective in the treatment of this complication. Early (within 24 h) PPB requiring therapy is often treated by immediate repeat endoscopy due to colon prep effect and rapid access to the site of bleeding. Delayed bleeding can be managed as per the algorithm below (Fig. 3.13). The techniques of colonoscopic EMR and control of PPB are manageable by the rural surgeon and can extend and improve the care delivered locally for our patients.

Fig. 3.13

Treatment algorithm for delayed post polypectomy bleeding (PPB). Modified from Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am, 42(3), Church J, Complications of Colonoscopy, 639–57, Copyright 2013, with permission from Elsevier

When to Transfer

The time to transfer the patient is prior to the polypectomy. If the polypectomy difficulty is beyond the skill of the endoscopist, simple biopsy can be done for diagnostic purposes and referral arranged to an endoscopist skilled in advanced techniques if the tissue diagnosis does not mandate operation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree