Table 9.1 Common concerns for terminal patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

are inadequately educated to care effectively for the dying. Finally, insufficient data are available to understand accurately end-of-life experiences. These problems can be corrected with changes in education for healthcare providers, updated guidelines for medical providers and regulatory agencies, increased utilization of palliative and hospice services, and increased research and public discussion about death and dying issues. Since this report, end-of-life care opportunities have improved for patients. For example, palliative and hospice care have recently been recognized as unique medical subspecialities in the United States and a recent survey reported that the number of United States hospitals offering palliative care programmes nearly doubled from 2000 to 20052.

deaths were not included. The most common causes of death, each accounting for one in three deaths, were cardiac and respiratory diseases. Cancer accounted for 14% of deaths. The most common symptoms and treatment for each were catalogued (Table 9.2). Pain was noted in nearly half of patients, with most treated with analgesics. An earlier prospective study of 200 consecutive hospice patients reported similar symptoms during the last 48 hours before death, with pain reported in 51%, with about half of these patients developing new pains and the remainder experiencing exacerbations of previously controlled pain5. Opioids were used by 91% of patients prior to the last 48 hours of life, with the dosage increased during the last 48 hours in 44%, unchanged in 43%, and decreased in 13%.

Table 9.2 Common symptoms and treatment during the last 48 hours of life | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

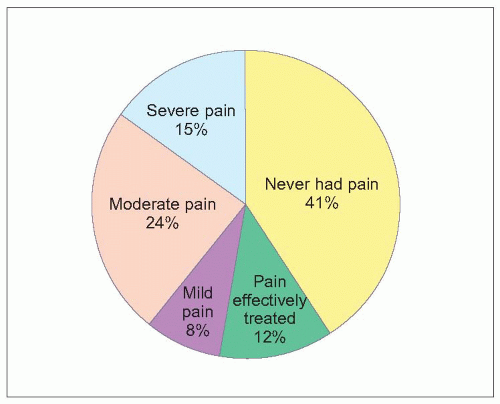

9.1 Pain during the last month of life. Caregivers for 674 patients dying in one of 230 long-term care facilities in four states in the United States (Florida, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Maryland) were interviewed about symptoms occurring during the last month of each patient’s life. Nearly 60% of patients experienced pain during their final month of life, with only 20% of those with pain reporting effective pain control. Pain was moderate-severe in 62% of those with pain. (Based on Hanson LC, et al., 20083.) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree