CHAPTER 14 Electrotherapeutic Modalities and Physical Agents

Description

Terminology and Subtypes

Physical modalities is a broad term referring to a variety of instruments, machines, and tools traditionally used in physical therapy for musculoskeletal conditions, including chronic low back pain (CLBP). Two important categories of modalities are electrotherapeutic and physical agents.1,2 Electrotherapeutic modalities involve the use of electricity and include therapies such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), electrical muscle stimulation (EMS), and interferential current (IFC).3 The term superficial TENS is also used to differentiate it from TENS administered through a spinal cord stimulator. Electroacupuncture is the application of electrical stimulation, typically with high frequency TENS, through acupuncture needles.

Physical agents are modalities that involve thermal, acoustic (produced by sound waves), or radiant energy, and include interventions such as therapeutic ultrasound (US), superficial heat (hot packs), and cryotherapy (cold packs or ice).3 US refers to acoustic energy above 20,000 hertz (Hz), and is used for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Therapeutic US uses more energy than diagnostic US, which is also referred to as sonography.4 Phonophoresis is the use of therapeutic US to facilitate the absorption of topical products such as analgesic or anti-inflammatory creams.5 The term physical modality should be distinguished from physical therapy, which refers to an allied health profession rather than any specific treatment administered by this profession. This distinction is akin to that between medication and medicine. The term passive modalities is also sometimes used to describe physical modalities in which no active participation is required by the patient, and to distinguish these interventions from active rehabilitation such as supervised exercise therapy, which is also used by physical therapists.

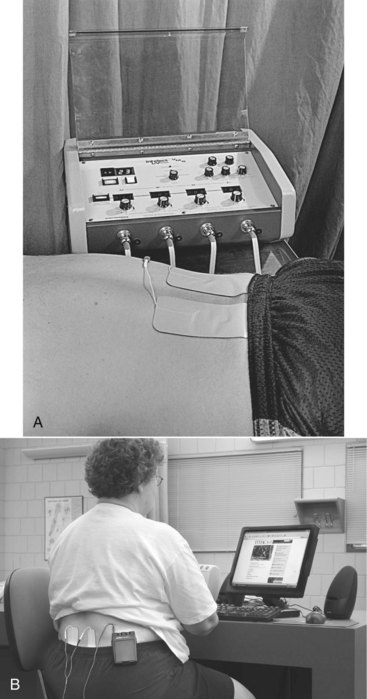

Within electrotherapeutic modalities, common interventions include TENS, EMS, and IFC. TENS delivers an electrical current through superficial electrodes placed on the skin around the area of symptoms and causes a tingling sensation by stimulating sensory nerve fibers. EMS also delivers an electrical current through superficial electrodes placed on the skin, but uses a different type of electrical current than TENS to target motor nerve fibers. IFC is also administered through superficial electrodes and uses a much higher frequency than TENS, which is thought to allow for deeper penetration of the electrical current and is thought to cause less discomfort. There are several types of TENS, EMS, and IFC devices available, including larger units intended for use in clinical settings and smaller, battery-operated units that may be portable and worn under clothing for prolonged use throughout the day (Figure 14-1).

Figure 14-1 Typical stationary (A) and portable TENS machines (B).

(Courtesy of Dewey Neild. In Pagliarulo MA. Introduction to physical therapy, ed 3. St. Louis, Mosby, 2006.)

Common physical agents include US, superficial heat, and cryotherapy. US produces sound waves that are transmitted to the affected area through a hand-held, wand-shaped probe using conductive gel. Settings on the US machine may deliver pulsed or continuous waves. Hot packs are typically reusable, moldable bags of gel that are heated and wrapped in moist towels before being placed on the affected area to provide heat (Figure 14-2). Cold packs are typically reusable, moldable bags of gel that are frozen and wrapped in moist towels before being placed on the affected area to provide cold (Figure 14-3). Both hot and cold packs are available as disposable types that create a temporary heating or cooling effect through a chemical reaction initiated by crushing the packs by hand, or as reusable types that need to be placed in the microwave or freezer according to manufacturer recommendations (Figure 14-4). Other types of physical modalities used in the treatment of CLBP and not discussed in this chapter include various types of laser therapy, electromyography/biofeedback, electromagnetic fields, diathermy, and vapocoolant spray.

Figure 14-2 Typical moldable and reusable hot pack.

(From Salvo S: Massage therapy: principles & practice, ed 3. St. Louis, 2008, Saunders.)

Figure 14-3 Typical moldable and reusable cold pack.

(From Salvo S: Massage therapy: principles & practice, ed 3. St. Louis, 2008, Saunders.)

History and Frequency of Use

Electrotherapeutic modalities and physical agents have long been used in the management of musculoskeletal disorders, including CLBP, mostly by physical therapists.1,2 Heat and cold have likely been used to relieve various types of pain symptoms for millennia. One of the earliest references to using electricity for medical purposes came from the scribe, Largus, who in Rome in 46 AD recommended placing live torpedo fish on painful areas to alleviate symptoms.6 The use of electrotherapeutic modalities grew following World War I, when injured veterans were treated for musculoskeletal injuries with therapeutic exercise, manual therapy, and electrical stimulation. IFC was developed in the 1930s, allowing for a more comfortable application of electrical stimulation than its precursors.6 The first TENS device was approved for use in pain management by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the 1970s, and portable units were introduced shortly thereafter.7 Clinical research comparing various types of electrotherapeutic modalities began to appear in the 1970s. Although modern electrotherapeutic modalities incorporate more sophisticated displays and an increasing number of programmable settings, their internal components are mostly unchanged in recent decades.

Physical modalities, including heat, US, and EMS, are often administered in conjunction with spinal manipulation by chiropractors for the management of low back pain (LBP) where permitted by scope of practice.8,9

A prospective study of health care utilization among 1342 patients with LBP who presented to general practitioners in Germany reported that 34% used local heat, 17% used electrotherapy, and 9% used TENS in the subsequent 1 year follow-up.10 Local heat was the most commonly reported service, electrotherapy was the fourth most common, and TENS was the seventh most common.

Theory

Mechanism of Action

Electrotherapeutic Modalities

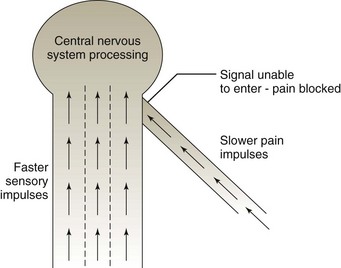

TENS may use low or high frequencies. At lower frequencies (5-10 Hz), TENS is thought to produce muscle contractions and provide pain reduction for several hours. At higher frequencies (80-100 Hz), TENS is thought to temporarily reduce pain by acting as a counterirritant stimulus.11 IFC is also thought to temporarily reduce pain by acting as a counterirritant stimulus. EMS provokes muscle contractions in the applied region, which is thought to act as a counterirritant stimulus, reduce muscle spasm, and increase muscle strength and endurance. A counterirritant stimulus is thought to provide pain relief through the gate control theory of pain (Figure 14-5). This theory proposes that input from sensory fibers other than pain (e.g., electrical stimulus) can override input from adjacent nociceptive fibers, thereby inhibiting perception of pain at the spinal cord level. EMS also delivers an electrical current through superficial electrodes placed on the skin, causing one or more adjacent muscles to contract, which is thought to promote blood supply and help strengthen the affected muscle.

Physical Agents

US may be applied in a continuous or pulsed manner. In the continuous setting, US converts nonthermal energy (e.g., acoustic energy) into heat that is thought to increase soft tissue extensibility and act as a counterirritant stimulus, thereby temporarily reducing pain. Pulsed US is thought to promote soft tissue healing by improving blood flow, altering cell membrane activity, and increasing vascular wall permeability in the applied region.11 US is thought to provide heat that can penetrate soft tissues at a much deeper level (e.g., 5-10 cm) than is possible through superficial heat (e.g., a few millimeters).

Superficial heat is thought to temporarily reduce pain by acting as a counterirritant stimulus, increasing soft tissue extensibility, and reducing muscle tone and spasm; these effects are noted mostly in superficial structures.11 Superficial heat may also promote muscle and general relaxation through vasodilatation while patients are lying on a treatment table. Cryotherapy is thought to temporarily reduce pain by acting as a counterirritant stimulus, decreasing nociceptive input and reducing muscle spasm; these effects are noted mostly in superficial structures.11 It is also thought to promote local vasoconstriction and decrease inflammation.

Indication

Electrotherapeutic modalities and physical agents are generally used for one of the following two main objectives: (1) to reduce pain, swelling, or tissue restriction; and (2) to increase strength, muscle activity, coordination, or rate of healing.3 These interventions are therefore indicated for nonspecific, mechanical CLBP.

Assessment

Before receiving electrotherapeutic modalities or physical agents, patients should first be assessed for LBP using an evidence-based and goal-oriented approach focused on the patient history and neurologic examination, as discussed in Chapter 3. Additional diagnostic imaging or specific diagnostic testing is generally not required before initiating these interventions for CLBP. The clinician should also inquire about general health to identify potential contraindications to this intervention.

Efficacy

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Electrotherapeutic Modalities

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found low-quality evidence supporting the efficacy of TENS in the management of CLBP.12

The CPG from Europe in 2004 found moderate evidence that TENS is not more effective than traction therapy, acupuncture, electroacupuncture, sham TENS, or placebo in the management of CLBP.13 That CPG did not recommend TENS in the management of CLBP.

The CPG from the United Kingdom in 2009 found weak evidence supporting the efficacy of TENS with respect to improvements in pain.14 That CPG did not recommend TENS for the management of CLBP.

The CPG from Italy in 2007 did not recommend TENS for the management of CLBP.15

The CPG from the United States in 2007 found insufficient evidence to make a recommendation regarding the use of TENS in the management of CLBP.16

Interferential Therapy

The CPG from Europe in 2004 found limited evidence that IFC is as effective as traction therapy and massage in the management of CLBP.13 That CPG also found no evidence that IFC is more effective than sham IFC and did not recommend IFC for CLBP.

The CPG from the United Kingdom in 2009 found insufficient evidence to support the efficacy of IFC for the management of CLBP.14 That CPG did not recommend IFC for CLBP.

The CPG from the United States in 2007 found insufficient evidence to make a recommendation regarding the use of IFC in the management of CLBP.16

Ultrasound

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found no evidence to support the efficacy of US in the management of CLBP.12

The CPG from Europe in 2004 found limited evidence that US is not effective for the management of CLBP.13 That CPG also found no evidence that US was more effective than other conservative management options for CLBP. That CPG did not recommend US for CLBP.

The CPG from Italy in 2007 did not recommend US for the management of CLBP.15

The CPG from the United Kingdom in 2009 did not recommend US for the management of CLBP.14

The CPG from the United States in 2007 found insufficient evidence to make a recommendation regarding the use of US in the management of CLBP.16

Physical Agents

Heat

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found no evidence to support the efficacy of heat in the management of CLBP.12

The CPG from Europe in 2004 found no evidence that heat was more effective than other conservative management options for CLPB.13 That CPG did not recommend the use of heat for CLBP.

The CPG from Italy in 2007 did not recommend heat for the management of CLBP.15

Ice

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found no evidence to support the efficacy of ice in the management of CLBP.12

The CPG from Europe in 2004 did not recommend the use of ice for the management of CLBP.13

Findings from these CPGs are summarized in Table 14-1.

TABLE 14-1 Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendation on Electrotherapeutic Modalities and Physical Agents for Chronic Low Back Pain

| Reference | Country | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| TENS | ||

| 12 | Belgium | Low-quality evidence supporting use |

| 13 | Europe | Not recommended |

| 14 | United Kingdom | Not recommended |

| 15 | Italy | Not recommended |

| 16 | United States | Insufficient evidence to make recommendation |

| Interferential Therapy | ||

| 13 | Europe | Not recommended |

| 14 | United Kingdom | Not recommended |

| 16 | United States | Insufficient evidence to make recommendation |

| Ultrasound | ||

| 12 | Belgium | No evidence to support efficacy |

| 13 | Europe | Not recommended |

| 15 | Italy | Not recommended |

| 14 | United Kingdom | Not recommended |

| 16 | US | Insufficient evidence to make recommendation |

| Heat | ||

| 12 | Belgium | No evidence to support efficacy |

| 13 | Europe | Not recommended |

| 15 | Italy | Not recommended |

| Ice | ||

| 12 | Belgium | No evidence to support efficacy |

| 13 | Europe | Not recommended |

Systematic Reviews

Electrotherapeutic Modalities

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

Cochrane Collaboration

An SR was conducted in 2007 by the Cochrane Collaboration on TENS versus placebo for CLBP.17 A total of four RCTs examining CLBP were identified; two allowed participants with prior back surgery to be included and one allowed patients with LBP with neurologic involvement to be included.18–21 For pain relief, three RCTs observed statistically significant decreases among those receiving TENS after 2 and 4 weeks of follow-up but only one RCT found clinically meaningful differences.18,19,21 None of the RCTs observed differences between TENS and placebo on the different types of functional outcomes, except for one RCT that found improved function on the Oswestry Disability Index for TENS but the difference was deemed clinically unimportant.20,21 Regarding general health status, one RCT observed no statistically significant differences between TENS and placebo, while another RCT found statistically significant benefits for four of eight subsections of the short-form 36 (SF-36) for conventional TENS and the same relationship was observed for two of eight subsections of the SF-36 for acupuncture-like TENS.19,21 This Cochrane review concluded that there was insufficient evidence supporting the routine use of TENS for CLBP.17 This SR also concluded that further research on TENS for LBP is warranted and that future RCTs should report baseline information, means and standard deviations for each treatment group, adverse events, and should also monitor use of analgesic medication, and examine long-term follow-up.

American Pain Society and American College of Physicians

An SR was conducted in 2006 by the American Pain Society and American College of Physicians CPG committee on nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic LBP.22 That review identified one SR related to TENS for CLBP, which was the Cochrane Collaboration review mentioned above.17 Five SRs that compared other interventions to TENS were also included.23–28

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree