32

Ear, nose and throat emergencies

The ear

Anatomy of the ear

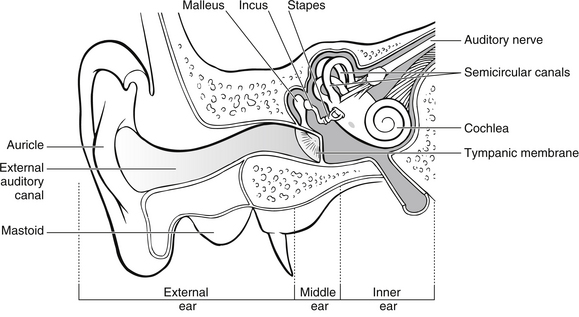

The ear is divided into three sections: external, middle and inner ear (Fig. 32.1). The outer ear funnels sound into the middle ear, which serves to transmit the sound to the auditory apparatus of the inner ear. The external ear consists of the auricle (or pinna), ear canal and tympanic membrane. The S-shaped ear canal is approximately 2.5–3 cm long and terminates at the tympanic membrane. The canal is lined with glands that secrete cerumen, a yellow waxy material that lubricates and protects the ear. Ear wax, sloughed off skin cells and dust may impair sound transmission through the outer ear, especially if a plug of wax attaches to the eardrum. The bone behind and below the ear canal is the mastoid part of the temporal bone. The lowest portion of this, the mastoid process, is palpable behind the lobule (Bickley & Szilagyi 2003).

The tympanic membrane (or eardrum) is a thin, translucent, pearly grey oval disc separating the external ear from the middle ear. It can easily be observed with an otoscope. The tympanic membrane vibrates and moves in and out in response to sound. The middle ear is an air-filled cavity containing three tiny bones, the ossicles, which are individually called the malleus (hammer), the incus (anvil) and the stapes (stirrup), so named because of their appearance. The malleus is attached to the tympanic membrane by a set of ligaments. The incus is attached to the malleus and they move as one. The stapes attaches to the oval window, the membrane separating the middle and inner ear. When the tympanic membrane vibrates in response to sound, the malleus and incus are displaced, and the stapes vibrates against the oval window continuing the transmission of sound. The pharyngotympanic tube, formerly known as the Eustachian tube, which connects the middle ear with the nasopharynx, allows the passage of air to equalize pressure on either side of the tympanic membrane. The inner ear is composed of several fluid-filled chambers encased in a bony labyrinth in the temporal bone. The semicircular canals are also important for balance (Zemlin 2011).

Infections of the ear

Clinical evidence and management: Acute otitis externa is essentially a localized or diffuse infection of the lining of the external auditory meatus commonly associated with organisms such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and occasionally fungi like Candida and Aspergillus (Sander 2001). Acute otitis externa frequently occurs following bathing or swimming because excessive moisture removes the protective cerumen from the ear canal allowing keratin debris to absorb water to create a nourishing environment for bacteria. For this reason it is often referred to as ‘swimmer’s ear’. Infection may be diffuse within the external auditory meatus or it may be focal in the form of a local swelling known as a furuncle, which may be extremely painful. Taking swabs for microbiological studies may not be well tolerated by the patient. It is essential that careful preparation of the patient takes place before any attempt is made to take a swab, especially if the individual is a child. Attempts to take a swab from an uncooperative child should be avoided as there is a risk that the tympanic membrane may be perforated by the swab if the child moves her/his head.

Treatment is based upon cleaning and drying the external auditory meatus. This should only be done after examination of the ear canal to determine the integrity of the tympanic membrane. Following cleansing of the external auditory meatus, topical medication containing steroids and antibiotics is necessary (Abelardo et al. 2007). Acute otitis externa largely results from identifiable causes and therefore lends itself to prevention strategies. The focus of much of the nursing care may revolve around educating the patient on keeping ears dry and on how to instill their prescribed medication.

Acute otitis media

Clinical evidence and management: Acute otitis media is often associated with systemic illness and fever, which may be attributed to the otitis media alone or occur in conjunction with coincidental upper respiratory tract infection (Ludman 2007). Acute otitis media is characterized by rapid onset of ear pain, headache, tinnitus, hearing loss, and nausea or vomiting. Infants and young children may present with irritability, crying, rubbing or pulling the ear, restless sleep and lethargy (Olson 2003). Children are often prone to acute otitis, with up to 30 % of those presenting with otitis media being children under three years of age, as the infection frequently results from upper respiratory tract infection of bacterial or viral origin.

Antibiotics are not often necessary in the treatment of uncomplicated otitis media with the mainstay of treatment being analgesia with antipyretic properties. Antibiotics in otitis media provide a modest benefit that must be balanced against the risk of adverse effects (Coker et al. 2010). In most cases involving children, antibiotics only provide symptomatic benefits after the first 24 hours, at which time symptoms are generally resolving. Serious complications, such as meningitis, mastoiditis, intracranial abscess, permanent hearing loss and neck abscess can develop as a result of otitis media (Olson 2003).

If the tympanic membrane has perforated, it is often the painful result of otitis media, trauma or foreign body insertion and is associated with loss of hearing. The individual should be advised to keep the ear dry and prevent water entering the ear. However, the ear should not be packed, and the patient should be advised not to do this at home, as it may prevent the discharge draining from the ear. More than 90% of tympanic membrane perforations heal spontaneously and management includes antibiotics, analgesia and antipyretics (Olson 2003). In some cases, where the tympanic membrane is intact, the infective material may cause the membrane to bulge, which also causes pain and loss of hearing. In such cases, admission to hospital is required in order that the tympanic membrane may be surgically perforated under general anaesthetic and grommets inserted to allow the discharge to drain out freely.

Mechanical obstruction

Clinical evidence and management: Cerumen may build up in the external auditory meatus, causing mechanical obstruction, which may be exacerbated by cleaning the ear with cotton-tipped buds. Such activities often cause cerumen to be pushed deep into the canal, causing impaction against the tympanic membrane. Obstruction in either case may cause a reduction in hearing, but rarely causes complete deafness. Impacted cerumen is often hard and resistant to removal by syringing alone; thus, in the ED the most appropriate management is to initiate a regimen to soften the cerumen using commercially available eardrops.

Foreign bodies

Clinical evidence: Older children and adults may present with a history of having a foreign body in the ear. Young children have a tendency to put foreign bodies in their ears, but as they often do not disclose this information, the nurse should be suspicious of children who present with earache, hearing loss and discharge from the ear. Small insects may also crawl into the ear canal and become trapped, causing a great deal of discomfort if still alive and buzzing.

Management: Foreign bodies may be removed using a variety of techniques including irrigation, suction and instrumentation, by individuals with the appropriate skills (Davies & Benger 2000). Care should be taken to ensure that this process does not impact the foreign body further in the ear, causing trauma to the external auditory meatus and the tympanic membrane.

Severe pain and distress are caused to patients when live insects enter the ear and they need to be killed in situ by the instillation of oil or lignocaine prior to removal (Davies & Benger 2000). Analgesic and/or antibiotic treatments should be prescribed as necessary.

Direct trauma

This is commonly caused by the insertion of objects either to clean the ear or to relieve itching, although any object inserted into the external auditory meatus has the potential to cause tympanic perforation. Objects frequently used are cotton-tipped buds and hair grips. In most cases, the ruptured tympanic membrane will heal spontaneously in 1–3 months (Bluestone 2007); however, ENT opinion should be sought. Pain relief and prophylactic antibiotics may be required, especially if the mechanism of injury includes contamination by water or a foreign body.