Don’t Treat Hypertension in Neurosurgery Cases Before Considering the Cause(s) and Risks, and Always Recognize that An Abrupt Change in the Patient’s Blood Pressure Needs to Be Investigated

John S. Marvel DO

The appropriate management of hypertension during neurosurgical cases requires knowledge of normal and pathological cerebrovascular physiology and consideration of the multiple causes of increased blood pressure. Like all things in anesthesia, simply “treating a number” without considering a cause risks worsening the patient’s condition.

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) depends on an adequate cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) and is well maintained via autoregulation over a wide range of mean arterial pressures (MAPs) in the normally functioning brain. CPP is determined by the difference between MAP and intracranial pressure (ICP):

CPP = MAP − ICP

Simply put, the body’s blood pressure, minus the pressure inside a nonexpanding calvaria, gives the perfusion pressure, which drives blood into the cerebral vasculature. Classically, CBF is maintained at a relatively constant level between MAPs of 50 to 150 mm Hg. Because the “average” ICP rests around 10 mm Hg and MAP for healthy adults is generally around 80 mm Hg, a goal CPP of 70 mm Hg should keep normotensive patients safely within the range of autoregulation. Some investigators have therefore adopted this CPP goal; however, there is no “standard” CPP target due to individual variability and disease state.

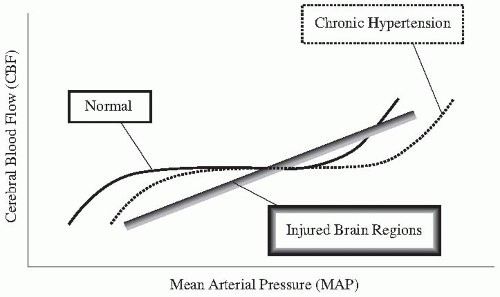

Chronic hypertension shifts the autoregulatory curve to the right (Fig. 135.1). This means that even “normal” MAPs may be relatively too low to maintain adequate CBF. This stresses the importance of knowing the patient’s baseline blood pressure values and taking them into consideration before treating hypertension. Also, autoregulation may be obliterated by certain conditions, such as ischemia (either by stroke or manual surgical retraction), and trauma. Without this ability to constrict blood vessels to maintain adequate CPP, MAPs that are adequate to perfuse a normal brain may be insufficient in the injured one.

FIGURE 135.1. Autoregulatory curves in three different scenarios: Normal brain function, chronic systemic hypertension resulting in a right-shift of MAPs to maintain cerebral blood flow, and injured brain, resulting in a loss of cerebral vascular autoregulation. (Adapted from Miller RD. Miller’s Anesthesia. 6th ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone; 2005.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|