Key Clinical Questions

How do I choose an appropriate opioid dose for my patient?

What adjuvant medications can I use for neuropathic pain?

How do I treat a patient who is experiencing a pain crisis?

When should I consult a palliative care or pain specialist?

How do I select an appropriate antiemetic for my patient?

How do I treat nausea in a patient with malignant bowel obstruction?

What nonpharmacologic strategies can I use to relieve my patient’s dyspnea?

What is an appropriate dose of opioid for treating dyspnea?

What do I say to family members who are concerned that morphine may hasten the patient’s death?

How do I manage loud secretions (“death rattle”) in a dying patient?

What do I say to family members who are distressed by the noisy secretions?

How do I evaluate an agitated dying patient?

How do I identify terminal delirium and distinguish it from other kinds of delirium?

What medications are useful for treating terminal delirium?

How do I counsel family members who are upset that the patient is no longer eating?

Are there any clinical situations in which artificial nutrition and hydration may be helpful for patients with advanced disease?

Pain

Studies of patient perspectives on end-of-life care universally report pain control as a major priority. Nonetheless, the literature shows that many patients with life-limiting illnesses experience poor pain control. In one well-known study (SUPPORT trial: Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments), approximately 40% of hospitalized patients experienced severe pain in the last three days before death.

When the focus of care is quality of life and comfort, any poorly controlled symptom should be treated as a medical emergency for that patient. Many patients already fear that pain will be an inevitable part of their disease process and that “nothing can be done.” Hospitalists play a vital role in correcting this misconception and ensuring that patients with advanced illnesses receive adequate pain control.

Pain can be described as nociceptive or neuropathic in origin. In nociceptive pain, peripheral nociceptors in the skin, musculoskeletal system, or viscera detect noxious stimuli and send impulses via afferent A-delta or C fibers to the dorsal horn of the spine. These signals are transmitted through ascending spinothalamic tracts to the thalamus and then to the cortex. Neuropathic pain occurs when the peripheral or central nervous system itself suffers damage or develops pathologic changes in sensitization. Neuropathic pain is generally more difficult to control than nociceptive pain. In reality, however, any type of chronic pain can significantly alter the sensory pathways and cause pathologic activation of the nervous system even after the initial pain stimulus has dissipated. The mechanisms of activation are quite complex and can involve central sensitization pathways, including multiple neurotransmitters (substance P, amino acid ligands), receptors (mu opioid, neurokinin-1, N-methyl-D-aspartate [NMDA]), and intracellular pathways (nitric oxide, protein kinase C).

It is important to recognize that the patient ultimately experiences pain not just as a physical phenomenon, but as an emotional experience. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) has defined pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage. While it is unquestionably a sensation in part or parts of the body, it is always unpleasant and therefore, an emotional experience.” Patients with life-threatening illness are especially vulnerable to emotional and cognitive factors that can influence their experience of pain.

Assessment of pain begins with a thorough history, including location, onset, duration, intensity, quality, and aggravating or ameliorating factors. The evaluation should also include a history of any associated functional decline, a psychosocial assessment (including exploration of any associated fears and concerns about disease progression), and a careful physical exam. The clinician should formulate a differential diagnosis of the clinical etiology of pain, which may include processes unrelated to the patient’s known terminal disease. For example, chest pain in a patient with breast cancer could be due to bony metastases, postradiation skin changes, cardiac ischemia, pulmonary embolism, costochrondritis, or gastroesophageal reflux disease.

The clinician should also determine the type of pain a patient is experiencing, as this will guide the appropriate treatment strategy.

- Nociceptive pain can be categorized as somatic or visceral. Somatic pain includes skin, musculoskeletal, or bone pain. It may be described as sharp, constant, throbbing, aching, and exacerbated by movement. It is usually well localized. Unlike somatic pain, visceral pain is generally poorly localized and arises from injury to organs or the lining of body cavities. It may be described as cramping, aching, tearing, deep, or a pressure sensation. Examples of visceral pain include symptoms from bowel obstruction, cholecystitis, or cardiac ischemia.

- Neuropathic pain can result from injury to any part of the nervous system, such as the peripheral nerves or spinal cord. Examples include postherpetic neuralgia, radiation-related brachial plexus injury, postthoracotomy pain, and phantom limb pain. Neuropathic pain is frequently described as burning, tingling, stabbing, electric, or shooting. It may also be described as aching. Physical findings may include allodynia, which is pain caused by a normally painless stimulus such as light touch. Neuropathic pain may also radiate.

- Some pathologic processes can cause a mixed pain syndrome that includes both nociceptive and neuropathic pain. One example is bone metastases to the spine, which may incite nociceptive, somatic bone pain as well as neuropathic pain from nerve root compression.

When a patient is unable to communicate, the clinician must then rely on the family or caregiver’s report and careful observation for nonverbal cues, such as guarding or grimacing with movement, to assess pain. One common misconception is that a patient who exhibits no physiologic signs of discomfort (such as tachycardia or hypertension) is unlikely to be experiencing pain. In fact, patients with chronic pain rarely show these signs of sympathetic arousal. These physiologic changes are more typically seen in acute pain, though even some patients with acute pain do not exhibit these signs.

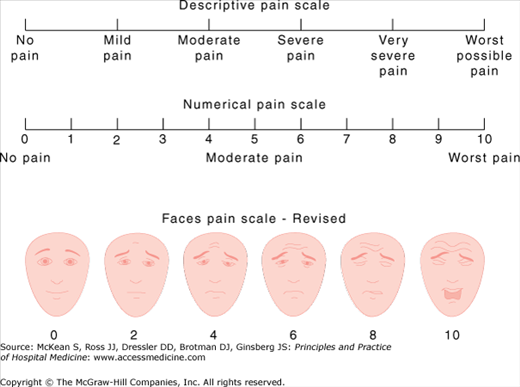

Several pain scales have been developed to monitor pain intensity and efficacy of treatment (Figure 217-1). Some patients may have no difficulty with the numerical pain scale, while others find it easier to report simplified categories of mild, moderate, or severe pain. Patients with mild cognitive deficits may be able to utilize the Faces Pain Scale, which was originally developed for pediatric patients.

Figure 217-1

Pain intensity scales. (From: Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford P, van Korlaar I, Goodenough B. Faces Pain Scale-Revised: Toward a Common Metric in Pediatric Pain Measurement. Pain. 93:173, 2001. This figure has been reproduced with permission of the International Association for the Study of Pain® (IASP®). The figure may not be reproduced for any other purpose without permission. Instructions on administering the scale are available at www.painsourcebook.ca.)

Diagnostic tests should be tailored appropriately to a patient’s overall goals of care. Generally, if a study has good potential to result in effective therapies (such as radiation) that would enhance a patient’s comfort, there may be reason to pursue the study even in the setting of advanced disease.

|

The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a well-known analgesic ladder that recommends the use of nonopioid analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen for mild pain, with the addition of opioids for moderate and severe pain. The WHO ladder also recommends consideration of adjuvant therapies such as antidepressants and anticonvulsants at any level of pain if appropriate. One should keep in mind that many patients with terminal illness have at least moderate to severe pain and thus will need an opioid immediately in addition to nonopioid analgesics.

Treatment choice should also be guided by the type of pain. Opioids are generally effective for nociceptive pain, including both somatic and visceral types. Somatic pain such as musculoskeletal or bone pain may also be quite responsive to NSAID therapy. Bone pain may require a combination of additional therapies including bisphosphonates, corticosteroids, calcitonin, or radiation therapy. Visceral pain from bowel obstruction may warrant an antisecretory agent to reduce bowel distension, such as a somatostatin analogue (octreotide) or an anticholinergic (scopolamine, hyoscyamine).

Neuropathic pain is often less responsive to opioids and requires the use of adjuvant medications. Table 217-1 shows common adjuvant medications for neuropathic pain.

| Drug | Drug Class | Starting Dose | Usual Effective Dose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gabapentin | Anticonvulsant | 100–300 mg orally every night at bedtime* | 300–1200 mg orally three times a day |

| Pregabalin | Anticonvulsant | 150 mg orally daily | 300–600 mg orally twice a day |

| Nortriptyline | Tricyclic antidepressant | 10 mg orally every night at bedtime | 50–150 mg orally every night at bedtime |

| Dexamethasone | Corticosteroid | 4 mg orally twice a day | Variable |

| Lidocaine 5% patch | Topical local anesthestic | 1 patch 12 hrs/day | 1–3 patches 12 hours/day |

| Capsaicin cream | Topical substance P modulator | 0.025% cream three times a day | 0.025–0.075% three to four times a day |

The mainstays in neuropathic pain therapy include tricyclic antidepressants and anticonvulsants such as gabapentin. Other agents that may be effective for neuropathic pain include corticosteroids, autonomic drugs (clonidine, prazosin, terazosin), lidocaine patches, and capsaicin cream. NMDA receptor antagonists such as ketamine can be considered for intractable pain but would require administration by a pain specialist.

The side-effect profile may greatly influence one’s choice of pain medication. NSAIDs are not recommended for those with significant risk of renal compromise, including patients who are elderly or have chronic kidney disease. Patients with multiple myeloma and a normal creatinine still carry a substantial risk for renal failure with NSAIDs. NSAIDs may also be contraindicated in patients at risk for gastrointestinal bleed or those on concomitant blood-thinning agents. Tricyclic antidepressants should be used cautiously in the elderly due to anticholinergic side effects. Nortriptyline is well studied and is generally considered the best tolerated tricyclic agent for the elderly, as it has the least anticholinergic activity. Opioids have some well-known side effects including constipation and sedation. However, because most patients with terminal illness will eventually need an opioid for adequate pain control, the clinician should become adept at dosing opioids and managing their side effects.

Many clinicians have received little formal training in pain management and do not feel fully confident selecting and dosing opioids. This discomfort may be exacerbated by misconceptions about opioids on the part of both clinicians and patients. Opioids rarely cause respiratory depression when dosed appropriately for pain. Studies have shown that patients with underlying lung disease such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can safely use opioids if dosed appropriately.

True opioid addiction is uncommon in terminally ill patients suffering from pain. Providers sometimes mistake behaviors like clock-watching or irritability as signs of addiction, but usually these are manifestations of pseudoaddiction in a patient receiving an inadequate pain regimen. These drug-seeking behaviors tend to cease when patients are given adequate doses at regular intervals.

Some patients and family members may not readily articulate their fears of opioid addiction. They may also worry that their disease is progressing or that they are “giving up” if they take opioids. Many patients directly associate morphine with dying. Clinicians should be attuned to these fears and educate their patients accordingly. It is also important to emphasize that pain medications will not advance one’s disease, and may in fact improve function by reducing pain.

Commonly used opioids include morphine, oxycodone, hydromorphone, fentanyl, and methadone. For most patients being initiated on opioids, there is not a compelling reason to choose, for example, hydromorphone over morphine. For certain patient populations, however, the choice of opioid does matter. Patients with significant renal failure should generally avoid morphine. The metabolites of morphine can accumulate in renal failure and cause neurotoxic side effects including myoclonus and delirium. Fentanyl and methadone are the safest opioids to use in renal failure patients including those on dialysis. Hydromorphone and oxycodone may be used cautiously in those with mild to moderate renal failure, with consideration of a reduction in dose or decrease in frequency. Similarly, patients with liver failure may need dose and frequency adjustments, but it is not clear that one particular opioid is significantly safer than the others in this setting.

Studies have shown that methadone may play a useful role in patients with severe pain who have responded poorly to other opioids or who have developed intolerable side effects. Methadone has opioid receptor activity as well as some antagonist NMDA receptor activity. It has good bioavailability and no known active metabolites (thus accounting for its safety in renal failure). However, due to a long half-life and complexities in dosing ratios, it should generally be initiated by clinicians with prior training or in consultation with a specialist.

Certain opioids are almost never recommended. Both meperidine (Demerol) and propoxyphene (Darvon) should be avoided because their metabolites can accumulate with repeated dosing and cause serious neurotoxicity such as seizures. Codeine should not be used for severe pain because it has a “ceiling effect” whereby further titration results only in increased side effects without improved pain relief. Furthermore, codeine must first be metabolized to morphine to provide analgesia, and approximately 10% of the population lacks the appropriate hepatic enzyme. These patients derive no benefit from codeine.

Equianalgesic doses: Different opioids have different potencies (ie, dose required to achieve a certain effect). Equianalgesic doses of two different opioids should achieve a similar degree of pain relief for most patients, although some patients may have idiosyncratic responses to different opioids due to genetically determined variations in metabolism. Table 217-2 shows equianalgesic doses of commonly used opioids. Looking at the table, morphine 10 mg intravenously should achieve similar pain relief as morphine 30 mg orally and oxycodone 20 mg orally. Misconceptions that “morphine does not work but hydromorphone does” may arise from a lack of knowledge of equianalgesic doses. A patient who finds no relief with morphine 4 mg intravenously but responds well to hydromorphone 1 mg intravenously may have in fact needed a higher dose of morphine (hydromorphone 1 mg intravenously is equianalgesic to approximately morphine 6.6 mg intravenously).

General opioid dosing guidelines:

- Table 217-3 lists reasonable starting doses and dosing intervals for moderate to severe pain in opioid-naive patients.

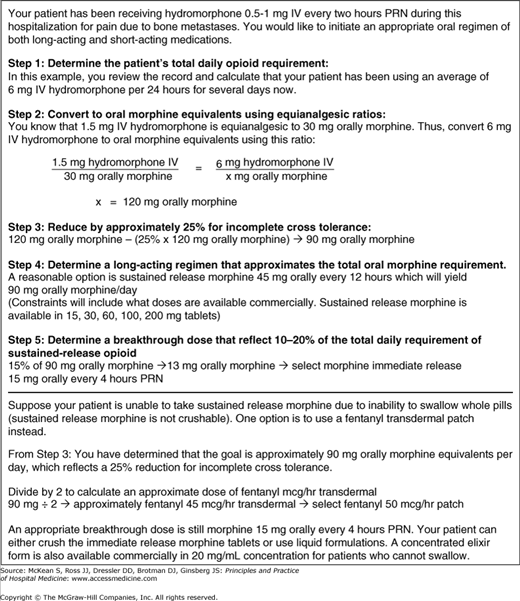

- Figure 217-2 demonstrates opioid conversions using simple mathematical ratios.

- Patients with chronic pain will need a long-acting pain medication (eg, sustained-release oxycodone or morphine, fentanyl patch, or methadone), not just short-acting medications. If unable to use a long-acting pain medication, chronic pain patients should at least receive a standing pain regimen with as-needed availability.

- Patients on sustained-release medications should also have a short-acting medication for breakthrough pain. Each dose of breakthrough opioid should be approximately 10% to 20% of the total daily requirement of the sustained-release opioid.

- If greater than three doses of breakthrough pain medications are needed in a 24-hour period, one should consider increasing the amount of sustained-release opioid. An appropriate increase would be 50% to 100% of the total amount used for breakthrough pain in 24 hours.

- When switching between different opioids, some experts recommend a 25% to 50% dose reduction after one has calculated the equianalgesic dose. This is to account for a phenomenon called incomplete cross tolerance, in which a patient who has developed some tolerance to the old opioid may not have the same degree of tolerance to the new opioid. The dose reduction is intended to reduce the risk of undesirable side effects.

| Drug | Initial Oral Dose* | Initial Intravenous Dose* |

|---|---|---|

| Morphine | 7.5–15 mg every 4 hours | 2–5 mg every 2 hours |

| Oxycodone | 5–10 mg every 4 hours | |

| Hydromorphone | 2–4 mg every 4 hours | 0.3–1 mg every 2 hours |

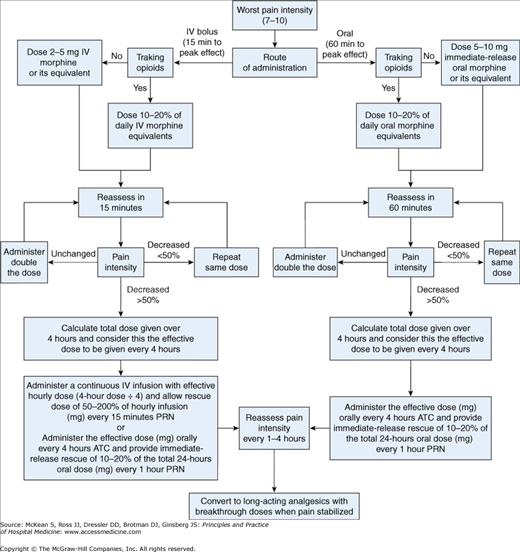

Patients with terminal illness, particularly those with cancer, may suffer severe exacerbations of pain from bone metastases, pathologic fractures, bowel obstruction, or other manifestations of progressive disease. When a patient presents with severe, uncontrolled pain (7–10 intensity), this is considered an acute pain crisis or palliative care emergency. Clinicians should treat these symptoms aggressively while determining the underlying cause. The American Pain Society (APS) has published guidelines on rapid titration of opioids for severe cancer-related pain. Figure 217-3 shows a treatment algorithm for severe pain that is adapted from the APS guidelines.

Figure 217-3

Management of acute pain crisis. (From: Rapid Titration with Short-Acting Oral or Intravenous Opioids. In Guideline for the Management of Cancer Pain in Adults and Children. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society, 2005. This figure has been adapted with permission of the American Pain Society.)

Infusions can be useful in certain settings but require a good understanding of basic principles.

- Opioid infusions should be used only when there is a specific indication. They should not be automatically started in a dying patient who is “comfort care” unless the patient has symptoms of discomfort.

- When using an opioid infusion to treat a patient who is not at the final stages of illness, the clinician should be attuned to patient fears that he or she may be actively dying. Many people associate a “morphine drip” with dying.

- Seek the advice of a pain expert before starting an infusion for a patient who is opioid-naïve.

- Patients who were previously on sustained-release oral regimens but are now unable to take pills (eg, surgery, bowel obstruction) need another means of fulfilling their baseline pain medication needs. For most inpatients, an opioid infusion is appropriate. The total daily oral need should be converted into intravenous morphine or hydromorphone equianalgesic units, then divided by 24 hours for an hourly infusion rate. Consider a 25% to 50% dose reduction for incomplete cross-tolerance if switching between opioids. Fentanyl patch (discussed later) is another option for those without intravenous access, but it is not appropriate for acute pain.

- Patients with severe pain who have required multiple IV bol-uses to control their symptoms are also potential candidates for opioid infusions. The initial infusion rate should be calculated based on their prior documented 24-hour needs, or if in an acute pain crisis, projected from their needs over the past 4 hours.

- Opioid infusion orders should not be written as broad ranges of “morphine 2–20 mg/hour, titrate to comfort.” This type of order gives no specific guidelines for titration and places the patient at risk of overdose if titration occurs too rapidly. A more appropriate order might be “morphine 2 mg/hour and morphine 2 mg intravenously every 15–30 minutes as needed for breakthrough pain. May titrate infusion to 4 mg/hour if patient requires greater than two boluses within one hour or for poorly controlled pain.”

- There should always be an additional order for as-needed boluses, either nurse-administered or through a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA). Most clinicians do not realize that it takes at least 8–12 hours to achieve new steady-state blood levels of morphine or hydromorphone after a change in the basal infusion rate. If one simply continues titrating up an infusion in a symptomatic patient without administering as-needed boluses, this patient is at risk of undertreatment of symptoms in the immediate setting as well as overdose/respiratory depression once the opioid reaches a new steady state in several hours.

- Bolus orders can be rapidly titrated for poorly controlled pain. Peak effect for morphine and hydromorphone boluses occurs within 15–30 minutes. If a particular bolus dose is inadequate, the dose can be safely increased every 15–30 minutes without needing to rapidly titrate up the basal infusion rate.

- The basal infusion rate should be reassessed every 8 hours but not more frequently. The infusion rate can be increased based on the amount of boluses required, but generally should not be increased by more than 100% at a time.

Patient-controlled analgesia may be used for patients with significant pain who are alert and able to use the equipment appropriately. PCAs should not be used in patients who have delirium, dementia, or other cognitive deficits. Table 217-4 shows commonly used PCA doses and lockout intervals in opioid-naïve patients. Higher doses may be needed in patients who have previously been on opioids. PCA pumps can be programmed to deliver patient-controlled boluses, a basal infusion, or both, though opioid-naïve patients generally should not be started on a basal infusion without the advice of a pain expert.

The fentanyl transdermal patch is another option for patients who cannot reliably take pills, but it is important to understand appropriate dosing and limitations of use:

- Equianalgesic dosing for the fentanyl patch compared with oral morphine appears earlier in this chapter (Table 217-2). Note that the commonly used fentanyl 25 mcg/hour patch is equianalgesic to approximately 50 mg oral morphine per day. Elderly or opioid-naïve patients should not be initiated on the 25 mcg/hour dose unless there is demonstrated need for this much opioid. A 12 mcg/hour patch is available, which may be more appropriate in these patients.

- The patch can take greater than 24 hours to reach peak effect. It is not appropriate for acute pain or if frequent titration is needed.

- Fentanyl patches are not recommended for patients with significant cachexia. The patch requires subcutaneous fat for effective absorption and release of drug.

- Fentanyl patches generally should not be used in febrile patients, as the uptake of medication is increased and can result in unexpected side effects (such as sedation) or poor analgesia if the patch runs out early.

Concerns about side effects from opioids often result in undertreatment of pain. Clinicians should make it a priority to recognize and treat opioid-induced side effects.

Many patients complain about mild sedation or “fogginess” when initially starting opioids or immediately after dose titration, but the effect usually wanes after two to seven days. If a patient complains of persistent symptoms and other causes of sedation have been ruled out (eg, other medications, metabolic disturbances, or central nervous system processes), one can consider several options:

- Reduce opioid dose (10% to 25%) if pain symptoms allow. Consider adding nonopioid adjuvant pain medications to acilitate dose reduction.

- Rotate to another opioid.

- Add a psychostimulant such as methylphenidate, with a starting dose of 2.5 mg orally twice a day and titrate up to a maximum of 1 mg/kg/day in divided doses. Psychostimulants should be avoided in patients with significant anxiety, arrhythmias, delirium, or psychosis.

Like sedation, opioid-induced nausea usually improves after the first week. This symptom is discussed in greater detail in the nausea section of this chapter. First-line therapies for opioid-induced nausea include dopamine antagonists such as prochlorperazine and haloperidol.

Unlike other opioid side effects, constipation does not wane with time. Patients taking opioids should be given a standing bowel regimen to prevent constipation. The combination of docusate sodium with senna is one option. There should be a low threshold to escalate the bowel regimen if symptoms persist. Some patients will need a combination of more aggressive laxatives including lactulose, polyethylene glycol, and enemas. Methylnaltrexone, a selective opioid antagonist, has been approved by the FDA for treatment of severe opioid-induced constipation. Unlike naloxone, methylnaltrexone does not cross the blood-brain barrier and provides effective relief of constipation without opioid withdrawal or reduction in analgesia. Methylnaltrexone can be given every other day as needed, and dosing is weight based:

| < 38 kg: | 0.15 mg/kg subcutaneously |

| 38–61 kg: | 8 mg subcutaneously |

| 62–114 kg: | 12 mg subcutaneously |

| > 114 kg: | 0.15 mg/kg subcutaneously |

Any mental status change in a patient taking opioids should be taken seriously. Delirium can cause a myriad of complications including injury, uncertainty in overall prognosis or assessment of disease progression, and a delay in discharge. Delirium can be particularly distressing because it compromises a patient’s sense of self. Patients may find this quite frightening, families often struggle with an enhanced sense of loss, feeling that they are losing their loved one even before death.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree