Key Clinical Questions

Introduction

Dizziness and vertigo are common complaints and encompass a myriad of symptoms that may stem from many organ systems. A sensation of lightheadedness or faintness may relate to the presence of orthostatic hypotension, abnormalities of the cardiovascular system, altered ambulation as seen in patients with impaired vision and sensation of feet (multiple-sensory-defect dizziness), or decreased position sense and reduced vision commonly experienced by elderly patients (benign disequilibrium of aging). Many patients describe dizziness in reference to impaired ambulation and fear of falling or when they have blurred vision or feel confused. Hyperventilation may also cause symptoms of dizziness. These symptoms may be associated with significant disability and possibly mortality.

|

On the other hand, the sensation of vertigo defined as an illusion of movement of self or surroundings is much more likely to be a reflection of an abnormality of the peripheral or central vestibular system. It may be physiologic occurring with seasickness or after spinning or pathologic of central or peripheral origin. The misuse of the term vertigo as a diagnostic term rather than as a symptom should be eschewed in favor of a recognized diagnostic entity. Simply assigning a diagnosis of vertigo could prematurely terminate the evaluation and thereby miss an opportunity for accurate diagnosis followed by appropriate treatment. In some cases, the term vertigo is used as shorthand for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Because of the high prevalence of this disorder in the outpatient setting, these patients may receive proper treatment despite sloppy documentation and failure to convey accurate information to colleagues.

This chapter primarily focuses on the symptom of vertigo in patients admitted to the hospital. Chapter 99 includes cardiac causes of presyncope, Other medical illnesses, drug toxicity, and substance abuse that may produce symptoms of dizziness and vertigo are covered elsewhere in this book. The studies reviewing a systematic approach to the diagnosis and treatment of the symptom of vertigo relate to the outpatient or emergency room settings. Hospitalized patients are a different population. If symptoms of dizziness and vertigo are new experiences, the clinician should consider iatrogenic causes in addition to the usual suspects.

A 75-year-old woman with diabetes and hypertension underwent a total knee replacement. On the first postoperative day, she experienced vertigo when turning in her hospital bed. Each brief vertiginous episode was associated with mild nausea. The patient was essentially asymptomatic when sitting or lying still. She did not suffer any perioperative hypotension. Physical and neurologic examinations revealed normal findings. What additional diagnostic testing should be considered? Physical and neurologic examinations reveal normal findings. What additional diagnostic testing should be considered? |

The Vestibular System

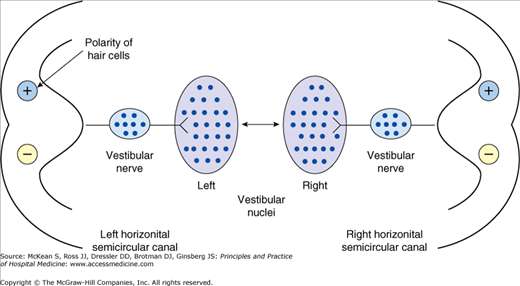

The vestibular system can be divided anatomically into the peripheral and central vestibular systems. The peripheral vestibular system consists of the left and right vestibular labyrinths and the eighth cranial nerve. The central vestibular system consists of the vestibular nuclei in the medulla and caudal pons and the pathways that subserve the vestibulo-ocular reflex, vestibulo-spinal reflexes, vestibular influences on spatial orientation, and the vestibulo-autonomic pathways that are important for the nausea and occasional vomiting that accompany vestibular system disease. Each vestibular labyrinth consists of three semicircular canals, which sense angular motion; and two otolithic organs, the utricle and saccule, which sense linear acceleration and orientation with respect to gravity. The vestibular labyrinth senses motion of the head. This signal is conveyed to the vestibular nuclei via the eighth nerve. At that site, vestibular signals are combined with signals from the visual and somatosensory systems to provide the central nervous system with an accurate representation of head orientation. With this information, the central nervous system can accurately control eye position and postural stability. Note that eighth nerve afferents have a nonzero tonic resting activity, which is illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 82-1.

Tonic signals from the left labyrinth drive the eyes and the body to the right, whereas signals from the right vestibular labyrinth drive the eyes and body to the left. At rest, these influences are balanced. During movement, the afferent activity from one labyrinth increases while the afferent activity from the opposite labyrinth decreases. This imbalance leads to movement of the eyes or the body as appropriate to maintain stable vision and upright posture.

Pathophysiology of the Vestibular System

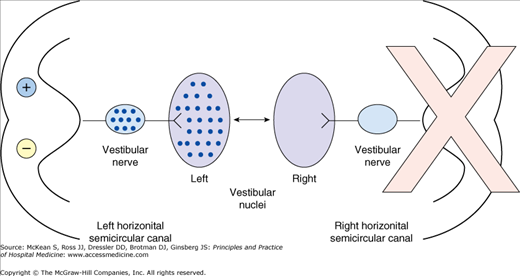

Vestibular disorders can be either peripheral or central. Most peripheral vestibular disorders affect only a single labyrinth. Damage to a single labyrinth causes a left-right vestibular imbalance. This imbalance is interpreted as intense movement toward the intact labyrinth, which leads to excessive eye movement in the form of nystagmus, gait instability, spatial disorientation, and autonomic symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and, in some patients, changes in heart rate and blood pressure, (ie, either hypotension or hypertension). The effects of a unilateral vestibular loss are illustrated in Figure 82-2.

Figure 82-2

The reciprocal push–pull interaction of the two labyrinths is disrupted after acute peripheral labyrinthine injury. For example, following the acute loss of right unilateral peripheral vestibular function, there is a loss of resting neural activity in the right vestibular nerve and right vestibular nuclei. Because the brain normally detects differences in activity between the two vestibular nuclear complexes, even when stationary the imbalance in neural activity is interpreted as a rapid head movement, in this case to the left.

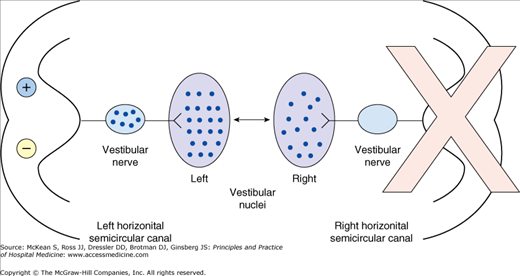

Over time, usually in a matter of days, central vestibular circuits rebalance despite the absence of a signal from one of the labyrinths. This process of rebalancing, known as vestibular compensation, leads to a gradual resolution of nystagmus and gait instability (see Figure 82-3)

Figure 82-3

When a peripheral vestibular injury is chronic, in this case on the right, the central nervous system is able, through vestibular compensation, to partially restore the lost resting activity within the deafferented vestibular nucleus, and thus reduce the asymmetry of neural activity between the vestibular nuclei at rest and partially restore the function of the vestibulo-ocular reflex.

Peripheral causes of vertigo include acoustic neuroma, aminoglycoside toxicity, benign positional vertigo, cholesteatoma, herpes zoster oticus, labyrinthine concussion related to head trauma, Ménière disease, perilymph fistula, otosclerosis, recurrent vestibulopathy, and vestibular neuronitis.

History of the Patient with Dizziness or Vertigo

The history is the most critical first step in distinguishing vertigo from other causes of dizziness and may pinpoint the etiology of the patient’s symptoms in up to three-fourths of patients. The examiner should carefully ask the patient what is meant by these symptoms and what brings them on. Some patients may be unable to explain their symptoms at all and respond simply that “I’m just dizzy.” Be sure to obtain an interpreter if English is not the primary language; do not make assumptions or characterize the symptoms for the patient in the interest of time. Most patients cannot adequately describe their symptoms because the sensation of dizziness and vertigo is not a normal sensation, and, unlike sensations such as vision and hearing, vestibular sensation does not have an associated vocabulary such as brightness, loudness, color, or pitch. Some patients complain of a head sensation such as light-headedness, heavy-headedness, foggy-headedness, or presyncope. These three general types of symptoms, namely a sense of motion, imbalance, and head sensations, are not mutually exclusive. A nonspecific complaint of a head sensation, especially light-headedness, does not exclude the possibility of a vestibular disorder whether peripheral or central, and it may result from a metabolic derangement, drug effect, or other organ system disease. In fact, dysequilibrium, reduced cerebral perfusion, and vertigo can all be associated with the symptom of dizziness with standing. Ask whether or not the dizziness is characterized by a sense of motion such as spinning, rocking or tilting, imbalance when walking, veering to the right or left, or if the patient fears falling or has fallen.

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree