Key Clinical Questions

Which conditions should prompt emergent ophthalmologic consultation?

Which conditions require prompt imaging and/or consultation with neurologists or neurosurgeons?

For hospital employees with viral conjunctivitis what are the recommendations to prevent nosocomial spread to hospitalized patients?

What are the risks of topical corticosteroids in patients with allergic conjunctivitis?

Introduction

Ophthalmologic concerns in the hospitalized patient fall into two broad categories: signs and symptoms of the systemic condition for which the patient has been admitted, and unrelated but potentially urgent disorders of the eye that may threaten vision. While some of the conditions discussed in this chapter may relate to the former issue, our approach will be to describe common ophthalmologic disorders for which inpatient consultation is often considered, and to provide information on appropriate triage and workup prior to obtaining the consultant’s opinion. In many cases, outpatient evaluation after the acute illness has passed may be more useful, since the patient’s cooperation with subjective testing methods is much more reliable. Symptoms that may prompt urgent evaluation include red eyes (with or without pain), double vision, and subjective loss of vision. There are a number of bedside examination techniques that do not require specialized equipment but can yield important information to narrow the differential diagnosis and help determine the urgency of further testing.

The consulting physician should perform a focused but detailed eye history and physical examination prior to consulting an ophthalmologist. Time of onset, monocular or binocular nature, duration, and associated neurologic symptoms are especially important. Past medical and ocular history are relevant, as are recent interventions during the current hospitalization that might contribute to the visual complaints. The examination should ideally include best corrected visual acuity (with glasses) measured for each eye, either with a near reading card or distance chart. It should be noted whether the pupils are equal in size and reactive to illumination. Abnormal extraocular movements may be seen with new binocular double vision. Peripheral vision testing with a small red object (pinhead, marker cap) can detect up to 75% of clinically relevant deficits. Finally, a hand-light examination should be done at the bedside to look for eyelid swelling or redness, conjunctival hyperemia and discharge, corneal clarity or haze, and gross iris and anterior segment abnormalities. If a direct ophthalmoscope is available, examination of the fundus should be attempted. This is best done in dim lighting so that the pupil is somewhat large. If a normal appearance of the optic nerves, retinal vessels, and maculae can be confirmed, this can be very helpful. This requires some level of practice and proficiency, but is within the scope of physical examination techniques of every physician.

Ophthalmologic consultation is required for any condition that may cause severe and permanent vision loss, including

|

The Inflamed Eye

In addition to the infections detailed below, loss of sympathetic innervation may give a mild red eye from vasodilation. When accompanied by ptosis (with or without miosis) as in Horner syndrome, this condition may be mistaken for ocular inflammation. Acute onset in a postpartum patient, with or without headache, may result from carotid artery dissection, and MR or CT angiography must be performed with consideration given to anticoagulation.

A 62-year-old woman is admitted for respiratory failure from a bacterial pneumonia. After 2 weeks of intubation in the intensive care unit on broad spectrum antibiotics, her condition improves. She is extubated and transferred to the medicine ward, where she reports eye irritation. Both eyes appear slightly red, and she reports some tearing and sensitivity to bright lights. Her vision is mildly blurred, and measures 20/25 in each eye with her reading glasses using a pocket visual acuity card. The remainder of her eye exam is essentially normal. This patient is likely suffering from exposure keratopathy or corneal abrasion (Table 81-1). Under normal conditions, the ocular surface and eyelid glands produce aqueous, oily, and proteinaceous tear secretions essential for normal eye health. Insufficient lubrication is common in the setting of an intubated and sedated patient and can lead to breakdown of the surface of the cornea with subsequent corneal infection and ulceration. For this reason, in such patients ICU protocols commonly include frequent lubrication of the eyes with ointments to prevent ocular surface disease. Despite this effort, mild damage to the cornea and conjunctiva, especially in a long hospitalization, may occur. Dry eye symptoms frequently include eye irritation, blurry vision, foreign body sensation, and mild eye redness. Other patients at risk include those with known facial nerve paresis, recent anesthesia with insufficient eyelid taping during the procedure, and dementia. Reassurance and further lubrication are warranted to relieve symptoms. |

| Conjunctivitis | Iritis | Acute Glaucoma | Corneal Infection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | Very common | Common | Uncommon | Common |

| Discharge | Copious | None | None | Watery |

| Vision | Unaffected | Slightly blurred | Severely blurred | Usually blurred |

| Conjunctival injection | Diffuse | Circumcorneal | Circumcorneal | Circumcorneal |

| Pain | None | Moderate | Severe | Moderate to severe |

| Cornea | Clear | Usually clear | Steamy | Variable |

| Pupil size | Normal | Small | Mid-dilated | Normal |

| Pupillary light response | Normal | Sluggish | Fixed | Normal |

| IOP | Normal | Normal | Elevated | Normal |

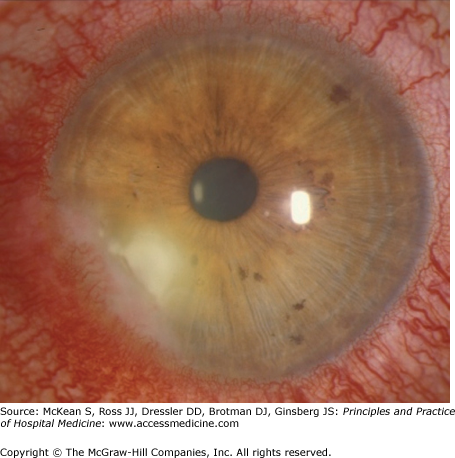

In contrast, a corneal ulcer presents as an opaque area in the cornea that may appear hazy or even white. The ulcer may have a significant mucopurulent exudate and will likely be very painful. The conjunctiva will frequently be bright red (Figure 81-1). At the bedside, the physician may use fluorescein dye to look for an epithelial defect. If corneal staining occurs, then the potential for corneal ulceration is high, even if an infiltrate is not yet seen and pain is minimal. Ophthalmologic consultation is required. Corneal ulcers may cause severe and permanent vision loss. The patient must be seen by an ophthalmologist that same day for culture of the corneal surface and broad spectrum topical antibiotic therapy to prevent corneal perforation and endophthalmitis, which frequently will lead to loss of the eye. The ophthalmologist may prescribe fortified topical antibiotic drops to be applied every 30 to 60 minutes around the clock for the first 24 to 48 hours, and the nursing staff must be made aware of the importance of adherence to this very demanding but effective medical therapy.

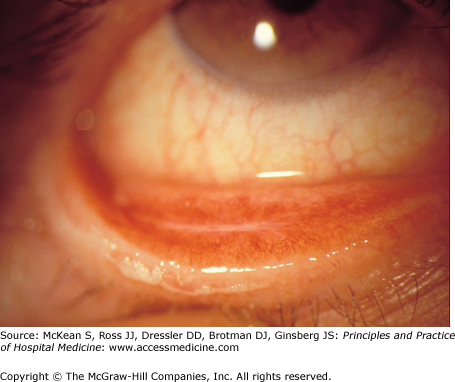

A 22-year-old man is admitted for respiratory distress attributed to an acute asthma attack. He is treated overnight with nebulized adrenergic agonists that are gradually weaned and prescribed systemic steroid therapy. It is also noted that he has mild eczematous changes on his hands that are not new. His roommate notes that he has had red eyes for the past 2 days, which have been itching and tearing as well. There has been no crusting of the eyelashes upon waking up and there is no frank pain. The eyes are mildly irritated, but itching has been the prominent feature. The skin beneath his eyelids is also slightly hyperpigmented. He has had similar episodes of red eyes before, which had resolved without serious complication. This case illustrates a classic example of allergic conjunctivitis. Severe itching is the most prominent symptom. Frequently, there will be generalized hyperemia (redness) of the conjunctiva and mild to moderate tearing (Figure 81-2). Visual blurring, if present, is mild and attributable to the tearing. Eye rubbing is typical, and the patient may have symptoms of allergic rhinitis as well, with associated rubbing of the nose. This rubbing can sometimes lead to mild eyelid edema and temporary hyperpigmentation (a.k.a. allergic shiners, raccoon eyes) and a crease on the nose from manipulation as well. Common associations are with asthma, eczema, or history of other atopy. Symptoms can be managed with artificial tear lubricants and cool compresses if mild to moderate. If symptoms are severe or persistent, inpatient consultation with an ophthalmologist may be warranted, and treatment may require immune modulation with a topical antihistamine, mast cell stabilizer, or mild steroid. Topical corticosteroids should never be prescribed without active participation by the ophthalmologist, since untoward effects may include promoting viral infection (especially if there is a history of ocular herpes simplex) and intraocular pressure elevation. |

Viral conjunctivitis also presents with bilateral red eyes. However, the symptoms will often have started in one eye 1 to 2 days prior to starting in the fellow eye. Often the eyes are very red with copious tearing, and the most prominent symptom is pain and burning. Mucous crusting of the eyelashes, especially in the morning, may be so copious as to preclude eyelid opening without manual assistance. A preauricular lymph node may also be palpated on exam and is relatively specific for viral etiology. Symptoms tend to worsen for the first few days of infection and generally resolve within 1 to 2 weeks. Household contacts may have had a recent URI or similar eye symptoms. Hand washing and contact precautions are crucial in preventing the spread of infection. If hospital workers become infected, they must be removed from patient contact for at least 7 days after symptoms start in the second eye to avoid nosocomial spread (spread to both eyes is very common even when infected persons are very cautious).