I. THE BLEEDING PATIENT: GENERAL PRINCIPLES

A. Etiology.

1. Bleeding disorders (

Table 88-1) may be secondary to the following:

a. Defects in the activity of platelets.

b. Defects in the activity of one or more coagulation factors (coagulopathy).

c. Congenital causes.

d. Acquired causes.

2. Hematology consultation is often necessary if the cause of bleeding is not immediately apparent and/or if specialized laboratory testing is required for diagnosis.

B. Diagnosis.

1. Clinical presentation.

a. Identify the site of bleeding.

i. Platelet disorders tend to cause mucocutaneous bleeding (e.g., epistaxis, oral, gastrointestinal [GI], genitourinary, ecchymosis).

ii. Coagulopathies (i.e., deficiencies in the activity of coagulation factors) tend to cause deep soft tissue bleeding (e.g., into joints and muscles).

iii. Bleeding from a single site (e.g., a surgical site, GI tract) warrants evaluation for an anatomic cause of bleeding.

b. Obtain the personal and family bleeding history.

i. Congenital disorders: life-long history of bleeding, positive family history. Exceptions are possible (e.g., mild hemophilia).

ii. Acquired disorders: often no previous history of bleeding, no family history.

c. Perform a careful physical examination.

i. Skin: ecchymosis, petechiae, or nonpalpable purpura.

ii. Hemarthrosis: warm, swollen joints.

iii. Mucosal surface abnormalities (e.g., nasal or oral pharyngeal mucosa).

2. Perform tiered laboratory evaluation.

a. Initial testing.

i. Complete blood count (exclude thrombocytopenia, assess for anemia).

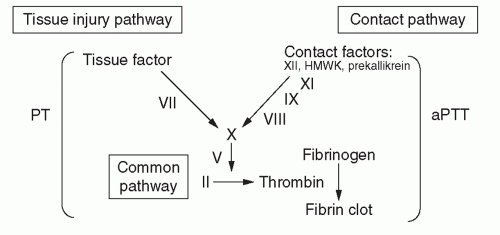

ii. Prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) (to exclude coagulopathy; see

Figure 88-1 and

Table 88-2).

(a) Prolonged PT may indicate defect in tissue injury (also known as extrinsic) pathway of coagulation.

(b) Prolonged aPTT may indicate defect in contact (also known as intrinsic) pathway of coagulation.

(c) Prolonged PT and aPTT may indicate single defect in common pathway of coagulation or multiple defects.

b. Specialized testing.

i. Mixing study (1:1 mix of patient and normal plasma) to detect when an inhibitior may be present.

(a) Indication: prolonged PT or aPTT.

(b) If prolongation completely corrects with mixing → suggests factor deficiency.

(c) If prolongation does not completely correct with mixing → suggests that an inhibitor is present (either specific to an individual coagulation factor or nonspecific, such as a lupus anticoagulant).

ii. Measurement of individual coagulation factor levels.

(a) aPTT prolongation: request factors VIII, IX, and XI.

(b) PT prolongation: request factors II, V, VII, X, and fibrinogen.

(c) von Willebrand factor (VWF) levels.

(d) Platelet function studies.

(e) FXIII levels.

II. ACQUIRED DISORDERS OF HEMOSTASIS

A. Antithrombotic therapy induced.

1. General Principles.

a. The medication administration history can suggest bleeding due to anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents that is common in the ICU. See chapter 90 on Antithrombotic therapy in critically ill patients.

B. Vitamin K deficiency.

1. Pathophysiology.

a. Inadequate dietary intake of vitamin K.

b. Malabsorption of fat-soluble dietary vitamin K.

c. Decreased production of vitamin K by intestinal flora (which may be destroyed by antibiotics).

2. Diagnosis.

a. Prolonged PT (corrects with mixing).

b. Decreased levels of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors (II, VII, IX, and X).

3. Treatment.

a. Phytonadione (vitamin K1) administration.

b. May be given PO or IV at a dose of 1 to 10 mg/day.

i. IV dosing associated with small risk of anaphylaxis.

(a) Administer over 30 minutes with close monitoring.

(b) Smaller doses (e.g., 1 mg) advised.

ii. SC dosing is discouraged due to erratic absorption.

c. Treatment may be given empirically without confirmatory laboratory studies.

i. PT should begin to normalize within several hours of IV administration of vitamin K1.

C. Coagulopathy of liver disease.

1. Pathophysiology.

a. Deficiency of hepatically synthesized clotting factors including the vitamin K-dependent factors (II, VII, IX, and X) and factors V, XI, XII, and fibrinogen.

b. Owing to any cause of liver disease that impairs synthetic function.

2. Diagnosis.

a. Prolonged PT ± prolonged aPTT.

b. Decreased levels of fibrinogen, factors II, V, VII, IX, X, XI, and XII.

i. Factor VIII, which is not produced in hepatocytes, is typically normal or elevated.

c. Other laboratory evidence of liver disease (e.g., decreased albumin, elevated alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase).

3. Treatment.

a. Blood products.

i. Should be administered only if bleeding, at high risk of bleeding, or when an invasive procedure is planned.

ii. Isolated mildly-moderately prolonged clotting times without bleeding not sufficient grounds for treatment.

iii. Ongoing treatment may be required until liver synthetic deficiency is resolved (e.g., by definitive treatment, such as liver transplantation, or recovery following shock liver).

b. Fresh frozen plasma (FFP).

i. Usual dose: infusions of approximately 10 to 15 mL/kg (usually 3 to 5 250 mL units).

ii. Severe hepatic failure and ongoing bleeding: consider continuous infusion (FFP drip).

iii. Goal: cessation in bleeding.

(a) A target INR of ≤1.5 is often cited but may be difficult to achieve.

iv. Be alert for signs of volume overload.

c. Cryoprecipitate.

i. Usual dose: 10 units per infusion is expected to increase fibrinogen levels by 50 mg/dL.

(a) Goal: cessation in bleeding and/or fibrinogen of ≥80 to 100 mg/dL.

d. Follow aPTT, PT, fibrinogen, and complete blood count every 4 to 8 hours if actively bleeding.

D. Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

1. Pathophysiology.

a. Uncontrolled activation of coagulation, which paradoxically may lead to bleeding due to consumptive deficiencies of multiple clotting factors and platelets.

2. Etiology.

a. Infection/sepsis.

b. Malignancy (e.g., acute promyelocytic leukemia, Trousseau syndrome).

c. Obstetrical complications (e.g., placental abruption; hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count [HELLP] syndrome; amniotic fluid embolism).

d. Tissue damage (e.g., trauma, burns).

e. Vascular abnormalities (e.g., abdominal aortic aneurysm, giant hemangioma).

f. Toxic procoagulant molecules (e.g., snake bite).

g. Fat embolism (e.g., fracture of long bones, sickle cell crisis).

3. Diagnosis.

a. Presence of an underlying etiology.

b. Laboratory testing.

i. Decreased fibrinogen (due to consumption).

ii. PT/aPTT may be prolonged (due to consumption of clotting factors).

iii. Thrombocytopenia may be present (due to accelerated platelet consumption).

iv. Increased D-dimer, a measure of cross-linked fibrin degradation products (due to accelerated fibrin degradation).

v. Red blood cell fragments (schistocytes) may be present on blood smear.

4. Treatment.

a. Treatment of the underlying cause (e.g., antibiotics for sepsis, delivery for pregnancy related).

b. Hemostatic therapy (for dosing, see

Table 88-3).