Opioid irrelevant pain

Pain is not just a physical experience. Patients with pain that does not respond to escalating doses of opioids should be reassessed and other contributors to their pain explored. “Total pain” is best treated by exploring the underlying issues, rather than using opioids. The term “total pain” is used to describe the final sensation of pain perceived by a patient, acknowledging that this perception can be exaggerated by factors other than a physically noxious stimulus—for example, psychosocial distress.

Pain that responds poorly to opioids

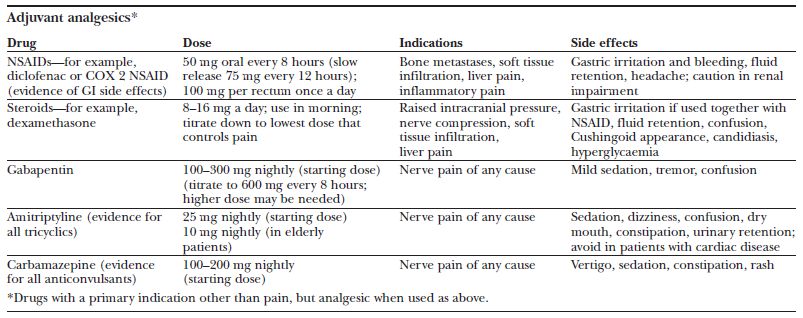

The European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) guidelines on the use of morphine and alternative opioids in cancer pain confirm oral morphine as the opioid of choice for moderate to severe pain. Dose titration with normal release morphine every four hours, with the same dose for breakthrough pain as required, is suggested. The patient’s 24 hour morphine requirement can then be reassessed daily and their regular dose adjusted accordingly. Measures to treat such patients include exploring psychosocial issues, managing the side effects, reducing the dose of opioid, switching to an alternative opioid, or changing the route of administration. The use of adjuvant drugs or co-analgesics may be appropriate, depending on the cause of the pain. Many such patients will have neuropathic pain.

Neuropathic pain

Nociceptive pain results from real or potential tissue damage. Neuropathic pain is caused by damage to the peripheral or central nervous system. A simple definition is “pain in an area of abnormal sensation.” Pain may be described as aching, burning, shooting, or stabbing and may be associated with abnormal sensation; normal touch is perceived as painful (allodynia). It may be caused by tumour invasion or compression but also by surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. Many patients have neuropathic pain that responds to opioids, and so initial management should include a trial of opioids. Patients who remain in pain will require additional measures.

The early addition of adjuvant analgesics, such as a tricyclic antidepressant or an anticonvulsant, should be considered. The number needed to treat is 3 for both categories. There is no evidence for a specific adjuvant for specific descriptors of neuropathic pain.

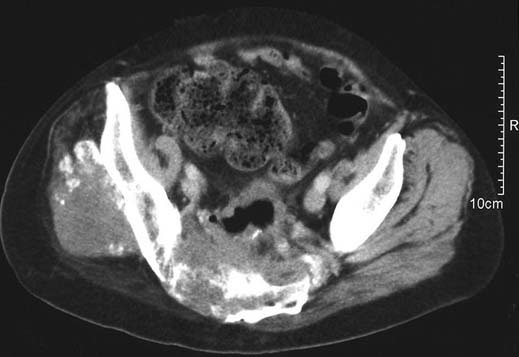

Computed tomography scan showing advanced pelvic disease from colorectal tumour resulting in severe pain

Classical changes associated with a brachial plexopathy due to a right Pancoast tumour: oedema, trophic changes, muscle wasting

In addition, there is no evidence for combining adjuvants. In clinical practice, an adjuvant is chosen for an individual patient after all symptoms and potential side effects are considered. Doses should be titrated to balance analgesia with adverse effects. If titration has reached a limit and pain has only partially responded then a second adjuvant may be added in some cases. This usually means a reduction in the dose of the first. A common example of combining adjuvants is gabapentin, which at maximum tolerated dose can sometimes be reduced to allow the addition of amitriptyline.

Non-pharmacological techniques

There are several non-pharmacological techniques for the management of neuropathic pain.

Psychological techniques

Psychological techniques, such as cognitive behavioural therapies, include simple relaxation, hypnosis, and biofeedback. These methods focus on overt behaviour and underlying cognitions and train the patient in coping strategies and behavioural techniques. Though this is clearly of more use in chronic non-malignant pain rather than in patients with cancer pain, simple relaxation techniques should not be forgotten.

Stimulation therapies

Acupuncture has been used successfully in eastern medicine for centuries. There does seem to be a scientific basis for acupuncture, with release of endogenous analgesics within the spinal cord. Acupuncture is particularly useful for myofascial pain, which is a common secondary phenomenon in many cancer pain syndromes.

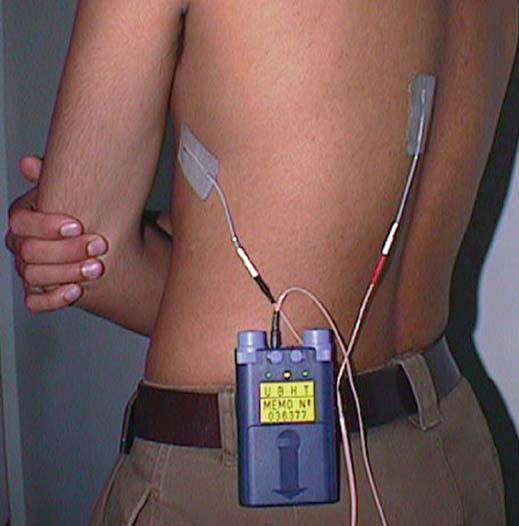

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) may have a similar mechanism of action to acupuncture. There is evidence to support its use in both acute and chronic pain.

Herbal medicine and homoeopathy are widely used for pain, but often with little evidence for efficacy. Regulations on safety for these treatments are limited compared with those for conventional drugs, and doctors should be wary of unrecognised side effects that may result.

Episodic pain

In 2002 an EAPC working group suggested the term episodic pain to describe “any acute transient pain that is severe and has an intensity that flares over baseline.” Episodic pain thus encompasses breakthrough pain and incident pain.

TENS for control of neuropathic pain that responds poorly to opioids

Breakthrough pain includes pain returning before the next dose of opioid is due or acute exacerbations of pain occurring on the background of pain usually controlled by an opioid regimen. Incident pain is usually defined as that occurring due to a voluntary action, such as movement or passing urine or stool. Pain due to bony metastases exacerbated by movement or weight bearing can be particularly problematic.

Incident pain

Patients with bony metastases in the spine, pelvis, or femora may have pain that escalates on movement, walking, standing, or even sitting. Opioid analgesics along with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are the mainstay of treatment, with the aim of making the patient comfortable at rest. Increasing the opioid dose further is often unhelpful as a dose sufficient to make movement possible is too sedating when the resting patient’s opioid requirement is decreased. Rescue or breakthrough doses of normal release opioid are usually used in anticipation of movement, along with non-drug measures such as radiotherapy, possible surgery, and appropriate aids and appliances.

Bisphosphonates are interesting drugs established in the prevention of skeletal events due to metastases in most solid tumours. In some patients, analgesia can be achieved acutely, and trial evidence is emerging for good analgesia in pain due to bone metastases.

Interventional techniques

Before interventional techniques are considered, it is important to exclude untreated depression, general anxiety, and distress (though untreated pain may also lead to any or all of these).

Chapter 2 discusses the role of trying a different opioid. The fundamental limiting factor in most patients with uncontrolled difficult pain is the inability to give higher doses because of side effects. It is worthwhile remembering all the strategies to “open the therapeutic window,” including using a different drug.

Methadone deserves a special mention in this context. It has unusual properties, which we do not fully understand. It has a different receptor binding profile from the pure μ agonists and can be remarkably potent at small doses.

It is not unusual to achieve markedly superior analgesia and a better side-effect profile with a switch to methadone. In addition, difficult elements of a pain—such as neuropathic or incident pain, or both—may become easier to control.

Starting or switching to methadone can be complicated in some patients, and specialist advice should usually be sought.

Invasive analgesic techniques

Despite appropriate use of analgesia and non-drug therapies, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy by multidisciplinary teams, a considerable number of patients will still have uncontrolled pain or unacceptable side effects, or both.

Such patients should be considered for some form of invasive analgesic technique as part of their overall management. This may range from a simple nerve block to more invasive techniques such as regional or neurodestructive blocks.

The choice of technique is influenced by:

- Patient’s expectations—Adequate assessment of pain is the first step in management. Involvement of patients and relatives is important and aids decisions about treatment

- Prognosis and required duration of analgesia—Although often difficult to predict, prognosis will affect how appropriate any particular intervention may be. Further planned oncological treatment may require short term use of interventions for pain control

- Pathology—The site and extent of disease will affect the response to analgesics and direct which interventions have a high chance of improving pain control. Plexus or nerve root involvement is common, as is incident pain

- Personnel—Early involvement of pain specialists in a multidisciplinary setting is important for planning analgesic strategies. This can help to minimise the length of stay in hospital and reduce problems with severe uncontrolled pain. Local availability of expertise and adequate training of staff and relatives must be considered when technique is selected.

Radiographs showing lystic lesions in femur (left) and internal stabilisation of bone (right)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree