Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage and Paracentesis

Mark L. Shapiro

Vanessa Schroder

I. GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF DPL

A. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) was first described in 1964 by Root as a method to identify the presence of hemoperitoneum in a hemodynamically unstable trauma patient.

B. Advantages.

1. Easy, fast, and versatile.

2. Can be performed in the trauma bay even in a patient otherwise too unstable to travel to computed tomography (CT) scan.

3. Allows for expeditious triaging of critically ill polytrauma patients.

4. DPL is sufficiently sensitive to detect small amounts of blood from minor injuries in stable patients with high-risk mechanisms of injury.

C. Definition of a positive DPL.

1. Blunt trauma.

a. 10 mL blood on initial aspiration.

b. RBC >100000/mm3 in lavage fluid.

c. WBC >500/mm3.

d. Amylase >175 units/dL.

e. The presence of food, particulate matter, stool, or bile.

2. The criteria for a positive DPL in penetrating trauma are the same as for blunt trauma save for the red blood cell (RBC) count being lowered to 10000/mm3 (or even lower at some institutions or in the setting of thoracoabdominal wounds).

3. In the case of a stable patient with an equivocal DPL, the catheter may be left in place and the lavage repeated in 2 to 3 hours.

II. ACCURACY

A. The accuracy of the physical exam for detecting intra-abdominal injuries is 55% to 65% in blunt trauma.

B. When done properly DPL is able to detect as little as 20 mL of blood.

1. The aspiration of 10 mL of frank blood in blunt and penetrating trauma patients has a positive predictive value of >90% for intra-abdominal injury.

2. The specificity of DPL for blood is very high, >95%; however, as DPL is unable to define the extent of intra-abdominal injuries, its sensitivity

for an injury requiring intervention is likely somewhat lower than this (especially in the case of blunt trauma).

for an injury requiring intervention is likely somewhat lower than this (especially in the case of blunt trauma).

3. This procedure is not sensitive for injuries to retroperitoneal structures, and conversely retroperitoneal injuries can lead to a false-positive DPL.

C. The accepted nontherapeutic laparotomy rate is 10% to 15% when the decision for laparotomy is based on the clinical situation and DPL alone.

III. INDICATIONS

A. Hypotension and the unstable trauma patient are the most common indications for DPL, and DPL will help delineate the etiology especially in a patient unable to give an adequate history of the traumatic event or participate in the physical exam.

1. Patients with blunt abdominal trauma have intra-abdominal injuries 13% of the time.

2. Hemorrhagic shock in blunt trauma is almost always due to intraabdominal injury of a vascular structure or solid organ. Even if another extra-abdominal source of hemorrhage is present, the abdomen should be evaluated for an additional site of bleeding.

3. As many as 10% of patients with presumed isolated traumatic head injuries will also have intra-abdominal injuries.

B. In addition to the hypotensive, unstable patient, a DPL is may be indicated in several additional clinical scenarios.

1. Patients with abdominal pain or tenderness on exam, abdominal wall bruising (including a seat belt sign), or distention.

2. Patients with unreliable physical exams, equivocal imaging, and mechanisms of injury that place them at high risk for hollow viscus injury.

3. Polytrauma patients already undergoing general anesthesia.

4. Patients with penetrating injuries where there is concern for the involvement of multiple body compartments (i.e., transdiaphragmatic).

5. Locations where appropriate cross-sectional imaging is not rapidly available.

C. The final decision to perform the DPL rests with the trauma surgeon who will be operating on and caring for the patient long term and is based on his or her clinical judgment.

IV. CONTRAINDICATIONS

A. DPL is only absolutely contraindicated when the decision to proceed with laparotomy has already been made based on the patient’s obvious traumatic injuries (i.e., penetrating abdominal wounds with evisceration).

B. Relative contraindications.

1. Patients with a history of multiple abdominal operations.

2. Patients with a distended abdomen including women in their second or third trimesters of pregnancy who have a higher risk of morbidity and mortality to both the mother and the baby.

3. Patients with obvious abdominal wall hematomas due to the high false-positive rate.

4. Lack of surgeon able to perform surgery.

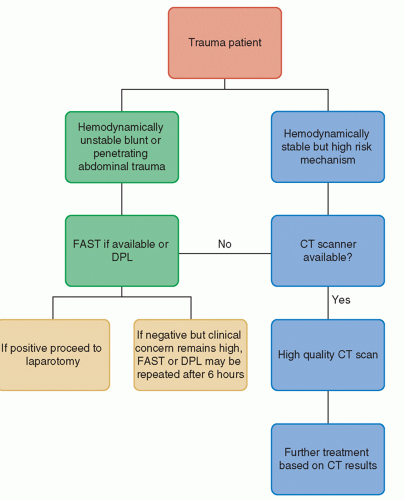

V. OTHER DIAGNOSTIC MODALITIES (Fig. 11-1)

A. CT scan is a rapid and noninvasive method of evaluating for intraabdominal injury that is reserved for hemodynamically stable traumatized patients.

1. CT has the benefits of identifying solid organ injuries that are likely amenable to nonoperative management (either close observation or interventional radiology) as well as being able to evaluate the retroperitoneum.

2. The downsides of CT scanning are cost, the need for IV contrast administration, as well as the inability to be used in unstable patients.

B. Focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST).

1. Ultrasound examination of Morrison pouch (right flank/hepatorenal space), the pouch of Douglas (pelvic), and the left flank/splenorenal recess in the abdomen for free fluid as well as the pericardium.

2. Performed during the secondary survey.

3. Advantages of FAST are speed, noninvasive nature of the test, the ability to be performed in the trauma bay in an unstable patient, and the ability for repeated, serial examinations.