Diagnostic Imaging of the Pediatric Trauma Patient

Stephen F. Miller MD, FRCPC

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING IN THE PEDIATRIC TRAUMA ROOM

The primary radiographic series for the pediatric trauma patient consists of:

Lateral cervical spine.

AP supine chest.

AP supine pelvis.

Extremity fractures can be imaged after the primary series.

Abdominal radiographs have no role in this setting.

Patients with clinically suspected cranial, thoracic, or abdominal trauma should undergo CT.

The role of ultrasound (FAST) in pediatric trauma is not well established, and is not routine at SickKids.

FAST does not serve as a substitute for CT and is of questionable prognostic value.

CT Imaging

Head CT

Noncontrast head CT is used to search for fractures, intracranial hemorrhage, or mass effect.

IV contrast may be administered to evaluate for vascular injuries and thromboses.

Abdominal CT

Abdominal CT is always performed with IV contrast.

Ensure that there is no preexisting allergy or profound renal impairment.

Use of oral contrast is controversial.

See Chapter 11 on Abdominal and Pelvic Trauma for discussion.

Should not administer oral contrast if patient is hemodynamically unstable or has conditions warranting emergency surgery, in order to prevent undue delay.

Thoracic CT

Thoracic CT is always performed with IV contrast.

Ensure that there is no preexisting allergy or profound renal impairment.

Used to search for vascular injuries such as aortic dissection, aortic rupture, pulmonary arterial or venous injuries.

Other Imaging

Standard contrast studies, such as upper GI series and contrast enema, are rarely used in the trauma setting.

Upper GI studies, using iso- or hypo-osmolar, water-soluble contrast, may help confirm or refute suspected duodenal hematoma or rupture.

Retrograde urethrography is the study of choice in suspected urethral injury in males.

Obtain spinal MRI for all patients with clinically suspicious injuries, especially those with neurologic deficits attributable to the spinal cord.

Rapid sequences can delineate with exquisite detail cord edema/contusion, cord discontinuity, and epidural hematomas.

MRI is indispensable for evaluating patients with craniocervical junction trauma.

LATERAL CERVICAL SPINE RADIOGRAPHS

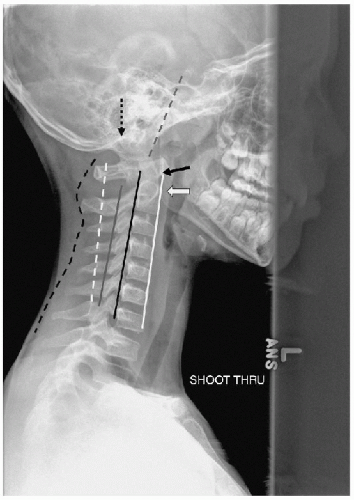

5-line, 3-column approach to the vertebrae (Fig. 4-1).

Prevertebral soft-tissue thickness anterior to C2-C3 is age-dependent and can vary with inspiration/expiration:

Age 0 to 2 years, allow 1 AP vertebral body thickness.

Age >2 years, prevertebral thickness anterior to C2-C3 should be less than 4 mm.

The clivodental line, drawn along the posterior aspect of the clivus, should intersect the posterior aspect of the dens.

Predental interspace should be less than 5 mm.

Using the 5-line approach, all lines should be regular, without stepoff or interruption, except for the most posterior, which undulates with the spinous processes (See Fig. 4-1).

In young patients, often see <3 mm gap at the craniocervical junction; if 5 mm or more, especially in high-speed MVA, obtain MRI.

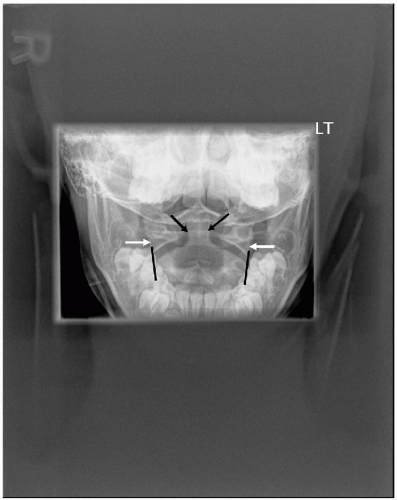

Once the lateral view is judged to be normal, obtain frontal and open-mouth odontoid views.

The value of the open-mouth odontoid view in young children is questionable. This view is often quite difficult to obtain in children younger than 5 years.1

In young children, most C2 fractures occur through the dens-body synchondrosis (synchondrotic slip)—this is usually readily apparent on the lateral view.1

In older children, once the lateral has been cleared, AP radiograph of the cervical vertebral column and an open-mouth odontoid view should be obtained. Oblique views are also recommended.1

If adequate plain radiographs cannot be produced, proceed to CT with sagittal and coronal reformatting.1

At SickKids, all cranial CT examinations begin at C2—pay close attention to the upper cervical spine on the lateral tomogram and on the axial images.

If there are multiple fractures, most occur at contiguous levels.2

AP and lateral views of clinically suspicious areas should be obtained—lateral views at minimum.

Assess vertebrae and disk interspaces for height and regularity—discrepant sizes of contiguous vertebrae or disks are suggestive of acute fracture and should be investigated with CT initially; MRI can follow to assess potential cord injury.

Significant spinal cord injury can occur in the absence of readily apparent vertebral trauma, due to ligamentous hypermobility.

Patients with neurologic deficits attributable to the spinal cord require MRI and CT to determine potential operative management.

Most pediatric vertebral fractures are in the thoracic region2:

T2-T10:

28.7%

L2-L5:

23.2%

Midcervical:

18.9%

Thoracolumbar junction:

14.6%

Cervicothoracic junction:

7.9%

Craniocervical junction:

6.7%

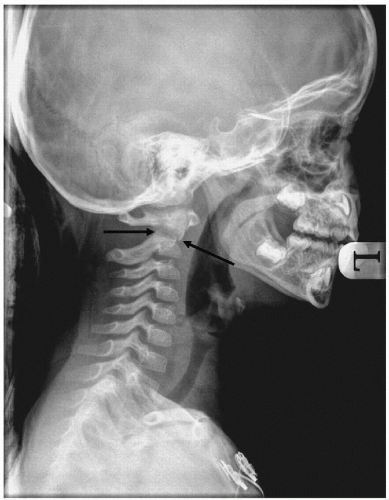

See Figs. 4-2 to 4-11 for interesting images of injuries of the C-spine.

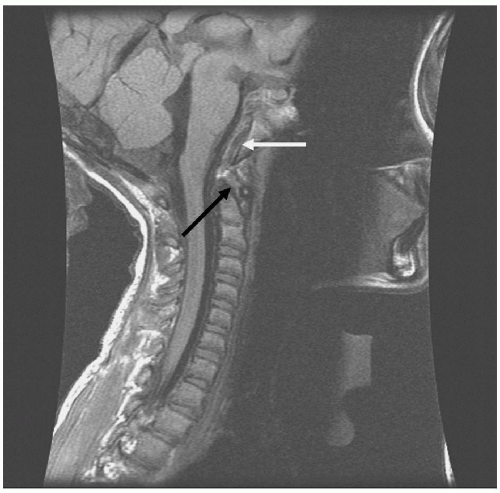

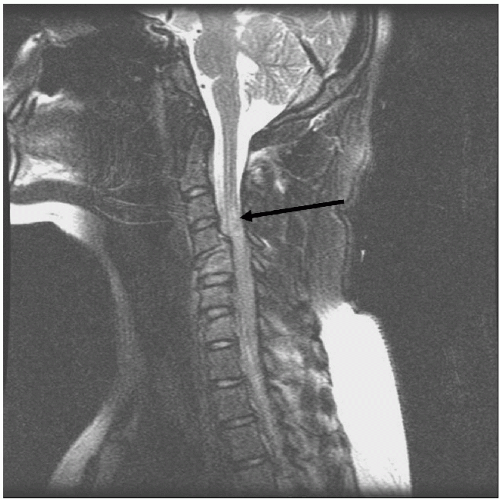

FIGURE 4-4 • Increased predental interspace. Sagittal T1-weighted MRI image from same patient as Fig. 4-3 demonstrates marked narrowing of the cervical spinal canal at the C1-C2 level (black arrow). (© Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto.) |

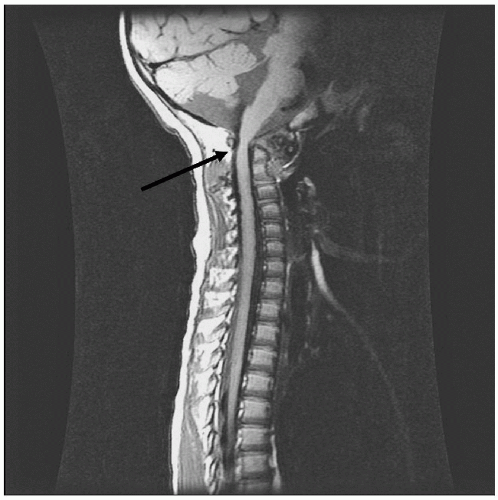

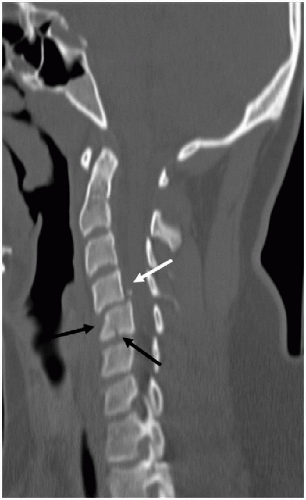

FIGURE 4-7 • C5 fracture. Sagittal reformatted images from CT of same patient as Fig. 4-6 demonstrate anterior compression fracture of the body of C5 (black arrows) and small retropulsed fragment posterior to the C4-C5 disk (white arrow). (© Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto.) |

FIGURE 4-8 • C5 fracture. Sagittal T2 MRI from same patient as Fig. 4-6 and 4-7 shows increased intramedullary signal within the spinal cord at C4-C5 (black arrow). Note the increased signal in the C5 vertebral body, consistent with edema/hemorrhage. The anterior compression fracture deformity at C5 is well demonstrated. (© Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto.) |

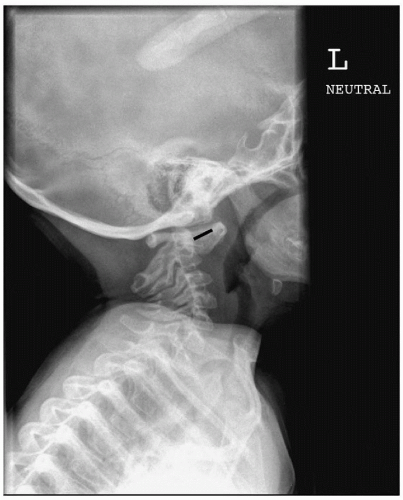

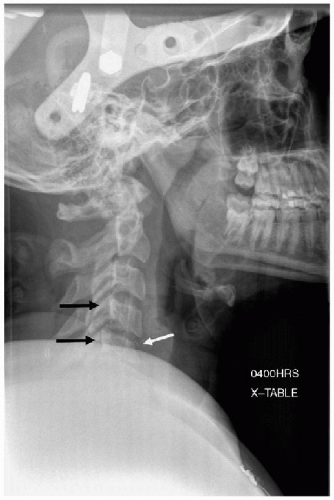

FIGURE 4-9 • Craniocervical junction injury. Lateral radiograph shows no definite abnormality. Patient was passenger in a high-speed MVA. (© Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto.) |

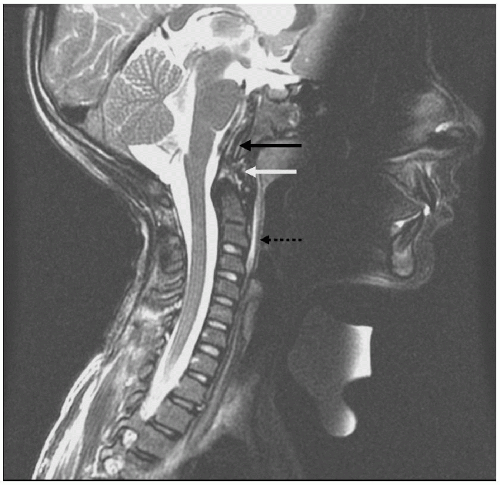

FIGURE 4-11 • Craniocervical junction trauma. Sagittal T2 MRI image from same patient as Fig. 4-10 shows abnormally hyperintense tissue (black arrow) between clivus and tectorial membrane, consistent with hemorrhage. Abnormal signal at tip of dens (white arrow) is also consistent with hemorrhage. Minimal prevertebral edema is seen (black dashed arrow). (© Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto.) |

PEDIATRIC THORACIC TRAUMA IMAGING

Anteroposterior (AP) chest radiograph is integral to the radiographic trauma series.

Indispensable for evaluating pneumothorax, presence and position of support catheters, detecting significant pleural effusions, and fractures.

AP chest radiograph is often inadequate in patients with significant blunt chest trauma, and may need to be followed with a contrast-enhanced chest CT if clinically indicated.

Chest Radiographs in the Pediatric Trauma Setting

AP (supine) chest radiograph is a component of the primary trauma series.

Assess for:

Pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum.

Hemothorax.

Fractures of vertebrae, shoulder girdles, ribs.

Position of support catheters.

Foreign bodies.

Pneumoperitoneum.

Cardiomegaly.

Atelectasis.

Pulmonary contusion.

Mediastinal widening.

Diaphragmatic integrity and position.

Upper abdominal viscera.

Pneumothorax is delineated from aerated lung by the presence of a thin dense line confined to the expected pleural space.

May be difficult to appreciate small pneumothoraces on supine films.

Pneumomediastinum will outline the thymus, cardiac borders, trachea, esophagus, and can extend into the neck, axilla, subcutaneous tissues, and abdomen.

Hemothorax is seen as a meniscus between aerated lung and the chest wall laterally or the diaphragm inferiorly. The supine film will show opacification/haziness of the hemithorax.

Carefully assess the position of endotracheal tube, naso/orogastric catheter, and vascular support catheters. If position is in question, obtain lateral radiographs.

AP technique causes artifactual enlargement of the cardiac and mediastinal silhouettes.

If cardiomegaly or pericardial effusion is suspected, obtain prompt echocardiography.

Evaluate suspected mediastinal widening with contrast-enhanced CT.

Children with clinically significant blunt or penetrating chest trauma should also undergo chest CT if hemodynamically stable.

Multislice CT scanners, with proper timing of IV contrast administration, allow for excellent depiction of thoracic vascular structures.

The most common CT finding in blunt thoracic trauma is pulmonary contusion.

Presents as nonsegmental, hyperdense, often crescentic foci that parallel the anterior, lateral, or posterior chest wall.

Majority (75%) of patients with significant contusions to the RML or RLL have concomitant right hepatic lobar or right renal trauma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree