Introduction

A diagnostic error is any mistake or failure in the diagnostic process leading to a misdiagnosis, a missed diagnosis, or a delayed diagnosis. This is an operational definition that includes any failures in the process of care, including timely access in eliciting or interpreting symptoms, signs, or laboratory results; formulating and weighing differential diagnosis; or lack of timely follow-up and specialty referral and evaluation. A diagnostic error is a construct that is usually based on reference to a subsequent test, clinical outcome, consultant’s diagnosis, or autopsy—gold standards that are themselves often imperfect or unavailable. Errors in diagnosis-related processes are ubiquitous, ranging from a trivial failure to ask an “insignificant” historical question to overlooking minor lab abnormalities, to switching specimens between two patients, to more serious errors in interpretation of data, which may or may not have adverse clinical consequences in terms of labeling a patient with an erroneous diagnosis or impacting clinical actions or outcomes. Detecting diagnostic errors is critical to correction of the ongoing care for a current patient, as well as for learning how to avoid similar errors in the future.

Although there is a paucity of data on the prevalence of diagnostic errors in everyday practice, studies using a wide range of approaches suggest that the error rate is not small, conservatively 10–15% for many diagnoses. Selected examples and rates from these studies are summarized in Table 8-1. These studies, however, have serious limitations. To better quantify the frequency and types of diagnosis errors and their clinical outcomes we need research to supplement these indirect and retrospective data with more direct, more encompassing (ie, looking at more than just one diagnosis or patients who die), prospective studies, similar to those that have been done with medication errors. This is necessary not only to determine the magnitude of the problem in various settings but also to gauge the effectiveness of interventions. Unfortunately, we lack reliable, validated, and efficient methods for carrying out such studies. We believe one future role for hospitalists will be to contribute to ongoing surveillance to help characterize the incidence and types of such errors.

| Type of Study | Study Example |

|---|---|

| Autopsy | Major unexpected discrepancies that would have changed the management are found in 10%. |

| Patient surveys | One-third of patients reported experience with a diagnostic error involving themselves, a family member, or close friends. |

| Second reviews—radiology | 10–30% of breast cancers are missed on mammography. |

| Second reviews—pathology | 6171 pathology specimens at Johns Hopkins were reread: major changes in prognosis or treatment were found in 1.4%. |

| Lab errors | 9% overall error rate, including pre- and posttest errors. |

| Standardized patients | Internists misdiagnosed 13% of patients presenting with common conditions in clinic. |

| Error databases | Of voluntary reports by Australian physicians, 34% were diagnostic errors, and these were judged to be the serious and least preventable. |

| Malpractice data | Diagnostic errors are the leading category of cases in most large organizations. |

| “Look back” reviews in specific diseases | Subarachnoid hemorrhage—30% misdiagnosed initially. |

It can be difficult to reach consensus about what constitutes a diagnostic error, and additional problems arise in judging its significance. Clearly we are most interested in learning from errors where there is an evidence-based consensus about the error and opportunities for its prevention. However, in a given case it is often not clear, even in retrospect, what is the correct diagnosis, or whether it could or should have been established earlier in the patient’s evaluation. More importantly, but often even more subject to conflicting reviewer judgment and limited evidence, are questions relating to outcomes. Would an earlier or different diagnosis in a given case have resulted in a more favorable outcome, and would different diagnostic decisions or strategies prevent similar errors and improve outcomes in the future?

Diagnosis, Diagnostic Errors, and Hospitalists: The Challenges

Diagnosis and diagnostic error play a special role in Hospital Medicine. Hospitalist physicians are in a pivotal position to either correct or perpetuate erroneous diagnoses given to patients in the ambulatory setting or emergency department. In addition, hospitalists must coordinate effective and efficient workups of undiagnosed problems or ones arising during the course of a hospital admission. Each day hospitalist clinicians must make numerous assessments on an array of diagnosis-related issues, including interpretation of changes in clinical status; deciding which tests to order and interpreting their results; deciding the likelihood that a new finding represents underlying diseases, as opposed to, say, a drug reaction; assessing the response to therapy (and recalibrating diagnostic likelihoods based on response or failure to respond); and skillfully sharing assessments and diagnostic uncertainties with patients and families. As the directors of the inpatient stay, the success of these endeavors falls squarely on the shoulders of the hospitalist.

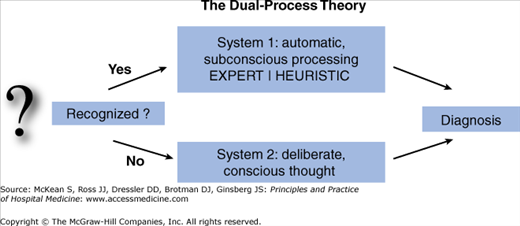

Research from cognitive psychology has shown that clinicians use two differing modes of diagnostic thinking, as illustrated in Figure 8-1. The first, labeled “System 1” by cognitive scientists, commonly referred to as “intuition,” is based primarily on rapid pattern recognition. At a subconscious and automatic level, many diagnoses are the result of quick recognition by experienced clinicians who have seen similar cases in the past. A simple example would be the visual recognition of a unilateral vesicular rash following a typical dermatome distribution, instantly diagnosed as herpes zoster. System 1 cognition is instantaneous, effortless, and very often correct. Unfortunately, it is also error prone, especially in relation to System 2 processing, the more conscious, deliberate, systematic, and analytical process that comes into play when we do not recognize an immediate solution. System 2 processing is also typically effective and correct, but invariably slower and can require more work. Using the framework of this dual process theory, we can understand how certain diagnostic errors simply reflect the acceptance of the first reasonable possibility that comes to mind (System 1), instead of pausing to consciously review other possibilities (System 2). Prematurely closing the thinking process in this way has been found to be a leading cause of diagnostic errors. On the other hand, given the efficiency of System 1 thinking, we would never make it through our rounds list if we worked exclusively in the mode of System 2.

Evidence shows that clinicians apply these approaches in remarkably varying and often idiosyncratic ways. Although most decisions are, in theory, based on clinical experience and an extensive understanding of the pathophysiology of disease, in reality decision making is a highly variable process, susceptible to a physician’s personal bias, tolerance of risk, institutional culture, and available time. Over the past 30 years a body of literature has demonstrated that these and other generic cognitive biases play a strong role in medical decision making—biases that can distort weighing of information and diagnostic assessments. Table 8-2 lists some of the common heuristics used to arrive at a diagnosis, and their potential pitfalls. These primarily affect System 1 cognition, but they can also influence System 2 processing.

| Heuristic | Description | Pitfall | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Availability | Estimating what is most likely by what is more common, recent, or more vividly recalled | Detracts from considering a broad and accurately calibrated differential | Overweighing brain tumor as cause of headache after recently missing a case |

| Representativeness | Pattern matching to the classic case | Overlooks accurate consideration of base rates of disease | Tendency to ascribe an unusual presentation to a rare disease rather than an atypical presentation of a common disease |

| Anchoring | Favoring initial information and impressions | Discounts subsequent information that may be critical | Failure to rethink a diagnosis suggested from the emergency department |

| Search satisficing (Premature closure) | Tendency to accept the first reasonable diagnosis that explains all the facts | Derails search for or consideration of alternate diagnoses | Delayed diagnosis of aortic dissection in a patient with chest pain thought to have angina |

| Confirmation bias | Seeking out and disproportionately weighing tests and facts that support prior beliefs and hypotheses | Selective and biased history gathering and testing strategies and interpretations | Dismissing symptoms as “nonorganic” in patient with known psychiatric diagnosis |

| Hindsight bias | Inclination to retrospectively view a diagnosis that was missed as obvious | Blame upstream clinicians for failing to diagnose what others “would never have missed” | In hindsight interpreting myriad celiac sprue symptoms as classic and unmistakable |

While there is agreement that these sorts of errors exist, there is little evidence or consensus about what should be done to minimize their distorting influences. Some argue that humans are “hard wired” to use these mental shortcuts, so it would be more fruitful to concentrate improvement efforts on systems and environmental changes to block or minimize their likelihood or impact. An alternative approach is cognitive “de-biasing”—training that would increase self-awareness and develop skills to resist succumbing to these biasing influences. Regardless of how amenable these influences are to such training, it is likely that a physician who is at least consciously aware of their potential mischief is better off than one who lacks such self-awareness.

Diagnosis: Challenges for Hospital Medicine

Atop these “cognitive” factors, hospitalists face unique and increasing stresses that add to the challenges of reaching accurate and timely diagnoses. These stressors, which are at times painfully obvious and at other times more subtle and unrecognized, call for a constant sense of heightened awareness and vigilance to avoid their potential adverse impact. These special challenges facing inpatient clinician diagnosis include the following:

Lack of prior knowledge of the patient, particularly a patient’s baseline mental status, functional ability, as well as the trust that derives from a longer-term relationship with a patient and family. This deficit goes beyond merely missing a particular piece of information from the history, but rather often means that important contextual information about patients and their daily activities, social situation, and health-related behaviors, beliefs, and barriers are often missing or deficient in Hospital Medicine doctor–patient relationships.

Missing past medical data and illness course, particularly when acutely ill patients are admitted with inadequate knowledge or capacity to give a good history and/or prior medical records are not readily accessible. Sorting out acute from chronic symptoms and illnesses is perhaps the most important diagnostic contribution an experienced hospital physician can make, yet this role is handicapped when key data are lacking. Complicating this problem is the ever-increasing reliance on shift coverage by both trainees and staff, increasing the likelihood that no one physician has a comprehensive picture of how the patient’s illness has evolved or responded to initial management.

In addition to missing data, information can also be misleading. Interpretation of derangements of electrolytes or renal or liver function may be compromised in the acute setting if baseline comparisons are not available, leading to the pursuit of transient or trivial abnormalities or overlooking more subtle but significant changes. Data can also be compromised by therapy started earlier (eg, negative cultures when antibiotics were started in the emergency department, clean-catch urine culture specimens that are not properly collected, or urine electrolytes sent after intravenous fluids or diuretics are started).

Prioritizationand diagnostic focus, vital for sorting out urgent problems and discerning causal relationships, is complicated in the setting of an acutely ill admitted patient. A major challenge is distinguishing which problems require rapid and definitive diagnosis and urgent intervention (eg, a seeding abscess or leaking aneurysm) versus which are secondary and can be put aside (eg, anemia, elevated blood pressure or blood glucose) while more urgent concerns are addressed. Triage and management decisions at times end up taking priority over diagnosis.

Divergent, conflicting, and sometimes excessive information from multiple sources, including data from the lab, imaging, and consultants. Given the plethora of data collected during the inpatient phase and because tests and advice are imperfect, this poses challenges and traps; for example, lesions that are seen on computed tomographic (CT) scans but not magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasonography, or vice versa. Similarly, consultants will each assess a patient and make diagnostic recommendations from their own vantage point. Collating and reconciling such input when the patient’s clinical situation is evolving can challenge the most experienced hospitalist diagnostician.

Transfers can fragment and complicate the diagnostic process. Handoffs in general are of concern (see Chapter 7), and we note the particular case of intensive care unit (ICU) transfers where attention to stabilization of critical organ failure often takes priority over keeping track of the entire patient and his or her problems. Monitoring or correcting hemodynamic or metabolic parameters in these settings may take precedence over connecting various findings to make explanatory diagnoses. Wading through thick charts of critically ill patients with multisystem failure makes it easy to overlook (or even stop searching for) underlying or iatrogenic diagnoses.

Trainees and diagnosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree