Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures in Pain Management

Milan P. Stojanovic

Take care not to get off soundings.

—James C. White

This chapter outlines the major diagnostic and therapeutic procedures performed at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Pain Center. Rather than attempting to cover the multitude of

advances in the field of Interventional Pain Medicine over the years, this chapter serves only as an introduction to the most common procedures. For a more detailed description of procedures, readers should refer to more detailed texts.

advances in the field of Interventional Pain Medicine over the years, this chapter serves only as an introduction to the most common procedures. For a more detailed description of procedures, readers should refer to more detailed texts.

I. GENERAL PRINCIPLES

1. Preprocedure Management

Patients are requested to consume only light meals on the day of a procedure and to take only clear liquids for 4 hours before the procedure. Baseline vital signs (including pain scale) are obtained on arrival in the clinic. If indicated, an 18- or 20-gauge intravenous (IV) catheter with a heplock is placed. An IV is placed routinely in patients undergoing procedures that are associated with a risk of sympathectomy and hypotension (e.g., lumbar sympathetic nerve block, celiac plexus block, etc.). The medical condition of the patient also could dictate that an IV should be placed (e.g., extreme anxiety, history of vasovagal syncope, and substantial cardiovascular disease). In general, premedication is avoided so that the baseline pain is not altered and so that patient cooperation is maintained. The patient is positioned appropriately, and monitors are placed as needed. Decisions about the level of monitoring needed are made on a patient-to-patient basis using similar criteria to those for IV placement. The usual monitors used are noninvasive blood pressure gauge, electrocardiograph (ECG), and pulse oximeter. Baseline verbal analog scores (VSA) and range-of-motion estimates are obtained before starting the procedure.

2. Choice of Injectate

(i) Local Anesthetic

For most of the diagnostic nerve/plexus blocks, a 1:1 mixture of equal parts 1% lidocaine and 0.25% bupivacaine are used. Lidocaine provides rapid onset of effect, while bupivacaine provides a useful prolongation of the effect so that patients can make observations that may have diagnostic value. Also, because of its prolonged action, bupivacaine may have a better effect on interrupting the “wind-up” phenomena in patients with chronic neuropathic pain. Although epinephrine can be used for somatic blocks, it should be avoided in patients with sympathetically maintained pain (SMP) because it may exacerbate their pain condition. In patients with history of anxiety, the epinephrine may cause a panic attack and is best avoided.

(ii) Steroids

The steroids currently used are depot preparations of methylprednisolone (Depo-Medrol) and triamcinolone (Aristocort), which may be irritating, and Kenalog, which is less irritating but allergenic. The doses generally range between 40 to 80 mg for epidural injection and 10 to 40 mg for peripheral nerve blocks. The steroids can be mixed with local anesthetics; however, we use small total volumes for all of our procedures performed under fluoroscopy. Studies have shown that if adequately placed under fluoroscopic guidance, even the small volumes can reach the site of pathology.

(iii) Contrast Media

Only nonionic contrast media should be used when performing epidural blocks (e.g., Isovue 300, Bracco DXS, Princeton, NJ). Standard contrast media can cause neurotoxicity and should be avoided. In case the standard contrast media is accidentally injected intrathecally, it should be irrigated with large amounts of normal saline. There is no clear consensus whether nonionic contrast should be used in patients allergic to the IV contrast solutions. If there is perceived risk of allergic reaction but the need for contrast agent is still present, the gadolinium can be used instead.

(iv) Neurolytic Agents

It is important to point out that neurolytic agents may exacerbate pain in neuropathic pain states. Therefore, their use should be mostly limited to patients with pain from cancer. Alcohol (50% to 95%) and phenol (6% to 10%) are the two agents commonly used for neurolysis. Alcohol has been extensively used as a neurolytic agent because it is effective and is easy to inject. It is the neurolytic agent of choice for injecting into the trigeminal ganglion, celiac plexus, and lumbar sympathetic chain. Occasionally, neuritis with intense burning pain is seen after alcohol neurolysis. Local anesthetics are injected prior to the neurolytic to localize the target nerve/plexus and to minimize the incidence of neuritis. The analgesic effect of phenol is almost equal to that of alcohol; however, it has the advantage of not producing neuritis. It is extremely viscous and difficult to inject (needs a larger bore needle and slow injection). Neither agent is isobaric in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (alcohol is hypobaric and phenol is hyperbaric); therefore, patients need to be positioned appropriately according to the baricity of the agent chosen. Neurolytic blockers have a delayed effect (up to 1 week), which generally lasts for up to 1 year.

3. Fluoroscopy Use

Recent studies strongly suggest the use of fluoroscopy for most procedures in interventional pain medicine. The fluoroscopy can improve accuracy of medication delivery, positively affect the outcomes, decrease complication rates, and improve validity of diagnostic blocks.

The radiation exposure to patients from fluoroscopy during common procedures is trivial, and not thought to be harmful. Caution is advised if fluoroscopy time exceeds 30 minutes. For the operator, most of the exposure arises from scatter, but it is very low. However, the use of a lead apron, thyroid shield, and dosimeter is recommended for the operator.

The accurate placement of needles can be challenging in obese patients and in certain complex procedures. A 25-gauge 3.5-inch or 22-gauge 6-inch spinal needle should be bent at a 20-degree angle 0.5 inch from its distal shaft to facilitate the placement. The “tunneled” or “coaxial” view can significantly help guide the needles to appropriate target points.

The negative aspiration of needles for blood return to rule out intravascular placement is a test with a high rate of false-negative results (up to 50%). Therefore, the placement of the needles should be verified with nonionic contrast injection.

4. Diagnostic Versus Therapeutic Procedures

Although therapeutic blocks are performed to potentially relieve pain for a prolonged period, diagnostic blocks are utilized

to identify the source of pain (e.g., facet joint and disc);

to evaluate the role of the sympathetic versus somatosensory nerves in maintaining pain;

as a predictor of outcome for further treatment [radiofrequency denervation, intradiscal electrothermal therapy (IDET), spinal cord stimulation, and surgical treatments];

as a predictor of drug class efficacy (e.g., IV testing of opioids and local anesthetics).

Before a diagnostic block is performed, the clinician must be sure that the patient has sustained reproducible pain and must document the activity or stimuli that evoke the pain. These factors can then be reassessed after the block and compared to the preblock state.

When performing diagnostic procedures, one should minimize patient sedation and procedure-related pain because both factors may interfere with the interpretation of effect and may lead to false-negative and false-positive results.

The use of placebo agents (e.g., saline versus local anesthetics) for diagnostic procedures is unethical and is strongly discouraged. This practice is likely to be helpful only in identifying placebo responders, not in identifying those with “real” versus psychogenic pain. Furthermore, the practice may damage the patient–physician relationship and may reduce the placebo effect of future treatments (see Chapter 3).

5. Complications

Many complications are common to all pain clinic procedures, and these are listed here.

The most common complication in the pain center setting is vasovagal syncope. Serious consequences can arise if procedures are performed in the sitting or standing position; therefore, it is advisable to perform procedures with patients lying down.

(i) General

Syncope, including vasovagal syncope

Infection, including cutaneous infection

Bleeding

Inadvertent intravascular injection

Inadvertent puncture of viscera

Seizure

Nerve penetration and injury

6. Postblock Management

Once the procedure is over, patients recover in the recovery room. The recovery time varies, depending on the procedure performed. Once the patients meet standard recovery room discharge criteria, they are discharged with an escort.

II. MOST COMMON PROCEDURES FOR LOW BACK PAIN

1. Epidural Steroid Injection

The presumed effect of steroid is to reduce the neuropathic pain, inflammation, swelling, and scarring. This pathology is a consequence of rupture of annulus fibrosus, causing radiculitis either by mechanical pressure from disc protrusion or by chemical irritation of the nerve root by leaking material from nucleus pulpous (phospholipase A2) resulting in radiculopathy-neuropathic pain. It has been shown that in neuropathic pain states the steroids can decrease the conduction in injured nerves. It also has been observed that steroids reduce the bulk of a scar by diminishing its hyaline portion, while leaving the fibrous skeleton intact.

The results of outcome studies for epidural steroid injection (ESI) are mixed. It is important to stress that many studies with negative outcomes did not use fluoroscopy and contrast media to verify the needle placement during the ESI. Recent, placebo-controlled studies using fluoroscopy strongly support the effectiveness of ESI, particularly the transforaminal approach. Although ESI is potentially indicated for axial (low back pain with no radiation to the leg), its role in treating that condition has not been extensively studied.

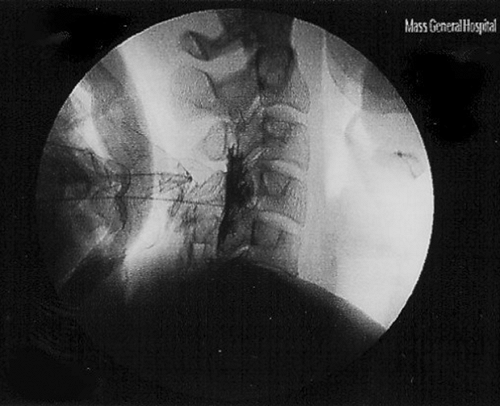

The use of fluoroscopy and contrast media is firmly supported in the case of ESI. In up to 30% of lumbar ESIs and 50% cervical ESIs, inadequate medication delivery is achieved without fluoroscopy. It is also important to place medication on the side of pathology because unilateral contrast spread is seen in 50% of the cases. There is significantly increased risk/benefit ratio if cervical ESI is performed without fluoroscopic guidance.

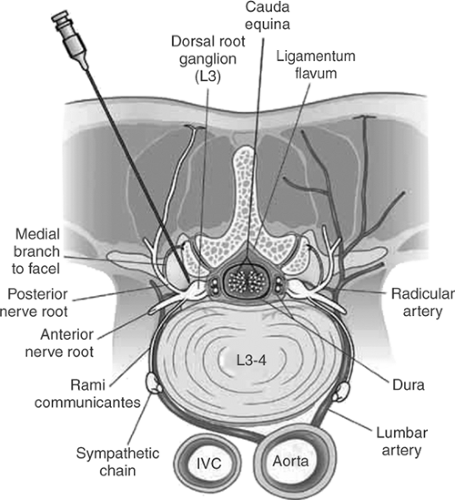

It seems that the transforaminal approach offers several advantages over interlaminar (see Fig. 1). This is particularly important in patients postlaminectomy. Several separate levels can be blocked at the same time.

Recent reports have revealed serious complications with the cervical transforaminal approach; this approach should be used only in carefully selected cases.

According to a recent national survey, the average number of ESIs per patient per year is five to seven. At the MGH Pain Center, we limit the number of ESIs per patient per year to four to six. Alternatively, a smaller dose of steroids per injection can be used and the total number of ESIs increased.

INDICATIONS

Radiculopathy due to mechanical or chemical nerve root irritation

Spinal stenosis

Certain cases of axial low back pain (discogenic pain)

SPECIAL COMPLICATIONS.

Intrathecal steroid injection, with potential complications such as anterior spinal artery syndrome, arachnoiditis, meningitis, urinary retention, conus medullaris syndrome, as well as a lack of effect.

BLOCK TREATMENT PROTOCOL.

There is no need to repeat ESI “series of three injections” if the first procedure fails to produce any effect. If the first procedure was effective but the pain has fully or partially returned, the procedure can be repeated after 4 to 6 weeks.

PATIENT POSITION.

Prone, feet over end of table, with a bunched-up pillow under abdomen (between iliac crests and costal margin) to reverse lumbar lordosis and for patient comfort is the recommended position. For the cervical approach, the pillow is placed under the chest (see subsequent text). Small support should be provided under the head if requested. Arms should be relaxed over the sides of table.

(i) Lumbar and Cervical Interlaminar Approach

TECHNIQUE

Achieve true anteroposterior (AP) fluoroscopic view (spinous process is midline to the pedicles).

Prepare skin with betadine and drape widely.

Mark the skin with Kelly clamp at the interlaminar foramen so that the clamp is ipsilateral to the site of pathology but not more lateral than the lateral margin of the spinous process.

Infiltrate the skin with 1% lidocaine (and small amount of sodium bicarbonate) using 25-gauge needle at the mark site (no need for the skin wheal).

Insert a 22-gauge Tuohy needle in a “tunneled” view and advance it until it sits in ligamentum flavum.

Obtain lateral fluoroscopic view and advance the needle until its tip is 3 mm posterior to the epidural space.

Check the AP fluoroscopic view so that the needle is not more lateral than the lateral margin of the spinous process.

Place a drop of normal saline into the hub of the needle.

Attach the loss-of-resistance syringe to the needle. Holding the syringe with one hand and the needle with the other, press firmly on plunger, maintain positive pressure constantly while rapidly oscillating the plunger. Advance the needle slowly and steadily until sudden loss of resistance is achieved and the saline disappears from the hub of the needle (allow only minimal air to escape). Save the images of lateral fluoroscopic view for later comparison.

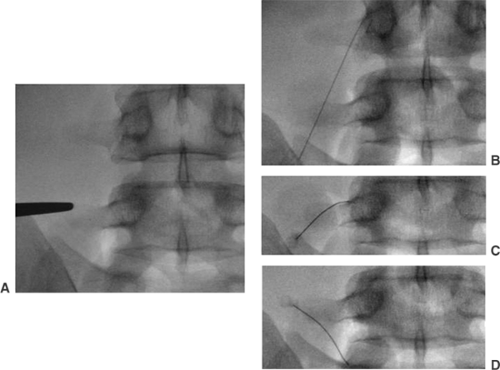

Inject 0.2 to 0.5 mL of nonionic contrast media and confirm its epidural spread using lateral fluoroscopic view (see Figs. 2, 3).

In AP fluoroscopic view, confirm adequate contrast media spread toward the site of pathology (see Fig. 4).

Inject 2 mL of triamcinolone (40 mg per mL) with 0.5 mL of 1:1 mix of 0.25% bupivacaine and 1% lidocaine (only 40 to 80 mg triamcinolone in cervical area).

Replace stylette in needle (to avoid tracking steroid through skin) and withdraw the needle.

Slowly raise the patient to a sitting position; do not leave him or her unattended until he or she is safely seated in a wheelchair because the legs may be weak and may buckle.

(ii) Lumbar Transforaminal Approach

Obtain oblique fluoroscopic view.

The target point is just caudal to the 6 o’clock point on the projection of the pedicle above desired level entry point.

Prepare and drape the skin in the usual manner and anesthetize the skin at the entry point.

Enter the skin in a “tunneled” view with a 3.5-inch needle bent at a 20-degree angle that is 0.5 inch from its distal shaft and advance the needle slowly.

The target point is a “safe triangle” with corresponding sides: (a) base = inferior border of the pedicle; (b) medial side = exiting spinal nerve; (c) lateral side = lateral border of the vertebral body.

The final position of the needle in AP view should be just below the midpoint of the pedicle, the position being just below the ceiling of the intervertebral foramen in lateral view.

Figure 2. Lateral fluoroscopic image of cervical epidural steroid injection with contrast media spread.

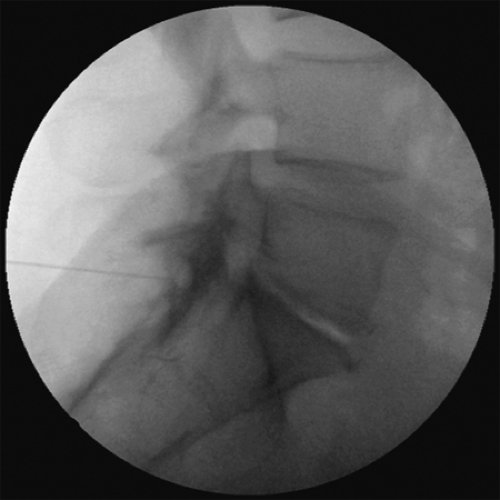

Figure 3. Lateral fluoroscopic image of L5-S1 interlaminar epidural steroid injections (ESI) with contrast media spread.

Figure 4. Anteroposterior fluoroscopic image of L5-S1 interlaminar epidural steroid injections (ESIs). Note the unilateral contrast spread.

Inject 0.2 to 0.5 mL of nonionic contrast media and confirm its epidural spread using AP and lateral fluoroscopic view after negative aspiration (see Fig. 5).

Inject slowly 1 to 2 mL of triamcinolone (40 mg per mL) with 0.5 mL of 1:1 mix of 0.25% bupivacaine and 1% lidocaine.

Keep in mind that the artery of Adamkiewicz enters the spinal canal in proximity to the nerve root from T7 to L4 spinal levels. Injection of particulate matter into artery may lead to spinal cord infarction.

Replace stylette in needle (to avoid tracking steroid through skin) and withdraw the needle. Slowly raise the patient to a sitting position. Do not leave the patient unattended until he or she is safely seated in a wheelchair.

(iii) Caudal Epidural Injection

The caudal approach may be used in patients with previous laminectomy. However, this approach has several disadvantages: (a) it does not ensure medication spread to the site of pathology, and (b) higher volumes of injectate should be used; therefore, medication that reaches the site of pathology will be diluted. The transforaminal approach is better suited to patients postlaminectomy.

The technique for this approach is achieved in lateral fluoroscopic view and final needle position should be checked by administration of contrast media.

(iv) Posterior S1 Foramen Approach

This approach is useful if epidural space is not otherwise accessible and especially when symptoms are confined to S1 or S2 level. Scan the sacral area briefly with the C-arm at different angles (remember that the sacrum takes off posteriorly from the lumbar spine at about 45 degrees) to see whether the posterior foramen can be made to overlie the anterior foramen. Usually only the anterior foramen is seen.

TECHNIQUE

Position: prone using C-arm fluoroscopy for visualization.

Using a 3.5-inch 25-gauge spinal needle, insert needle (C-arm in caudal direction) 1 inch posterior to the L5-S1 facet joint.

The needle is advanced at 45 degrees caudally, to strike the posterior surface of the sacrum.

The needle is then moved about until it falls through the posterior foramen.

The posterior foramen is usually found somewhat cephalad and lateral to the superomedial border of the elliptical image of the anterior foramen.

For epidural injections, the needle point is advanced 1 cm through the posterior foramen.

To block the S1 root, the needle is advanced another 1 cm until a paresthesia is achieved at the anterior foramen.

Needle position is confirmed in the lateral view with injection of the small amount of contrast media.

Inject 1 to 2 mL of triamcinolone (40 mg per mL) slowly with 0.5 mL of 1:1 mix of 0.25% bupivacaine and 1% lidocaine.

2. Facet Joint Medial Branch Blocks

The degenerative arthropathy of facet (zygapophysial) may lead to chronic pain. The physical examination and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings are nonspecific, and the best diagnostic test for facet pain is a diagnostic medial branch or intraarticular block with local anesthetics.

(i) Lumbar Facet Joint Innervation

Each lumbar facet joint is innervated by a medial branch of the posterior primary ramus of the lumbar nerve at the same level and another medial branch from one level above. For example, the L4-L5 facet joint is innervated by the medial branches of posterior primary rami of L4 and L3 nerve roots. The L5-S1 facet joint, however, is innervated by the medial branch of L4 posterior primary ramus and the dorsal ramus of the L5 nerve root.

(ii) Single-Needle Medial Branch Block

The single-needle technique seems to offer several advantages over the multiple-needle technique, including decreased procedural pain. It may even lower the rate of false positive blocks.

TECHNIQUE

Place the patient in a prone position.

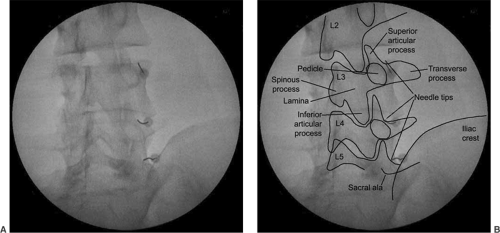

Obtain an AP fluoroscopic image visualizing L4 and L5 transverse processes and L4-5 and L5-S1 facet joints on the affected side. The AP fluoroscopic view is the only fluoroscopic view needed for this technique.

A 3.5-inch curved spinal needle should be inserted into the skin at the most lateral margin of the L5 transverse process. Local anesthetic for the skin should be administered through the same needle.

The needle should be then navigated medially with the aid of its distal curve. The contact with the bone should be made at the most medial and cephalad aspect of the transverse process (at the lateral margin of the silhouette of the superior articular process—SAP) (see Fig. 6).

A 0.3 mL of contrast (Omnipaque 240) should then be administered, making sure that the satisfactory spread without diffusion into adjacent neural structures (i.e., epidural space and intervertebral foramina) is achieved and that there is no vascular runoff. At this point, 0.3 mL of 1% to 2% lidocaine should be injected through the needle.

After blockade of the L4 dorsal ramus medial branch, the needle should be withdrawn close to the skin without exiting it. In a manner similar to that just described, the needle should be then navigated to the L4 transverse process and the same procedure should be performed for the L3 dorsal ramus medial branch. The same procedure should be repeated for the L5 dorsal ramus, by placing the tip of the needle at the junction of the ala of the sacrum with the SAP of the sacrum.

(iii) Multiple-Needle Medial Branch Block

The C arm is rotated to an oblique view until the vertical line of the facet joint is at the middle to outer one third of the endplate.

Lidocaine (1%) is used to anesthetize the skin and the needle pathway, except the area near the target point.

The target point of block is just caudal to the most medial portion of L2 to L5 transverse process for the L1 to L4 medial branches respectively. That is high at the “Scotty dog’s eye” (see Figs. 7, 8). For the dorsal ramus of L5, the target point of the needle is at the junction of the sacral ala and the SAP. Posteroanterior (PA) view is used for the block of the L5 dorsal ramus.

A 25-gauge, 3.5-inch spinal needle with a curved tip is used. The point of needle insertion is on the skin directly over the target point, and the tunneled view is used to advance the needle to the target point.

Insertion is terminated once the tip of the needle strikes the bone of the target point. The final position of the needle should be confirmed in AP view. The needle tip should be at the lateral margin of the silhouette of the SAP and slightly caudal from the superior margin of the transverse process.

Once the needle is in the correct position, 0.3 mL of contrast (Omnipaque 240) should be administered by the physician, making sure there is satisfactory spread without diffusion into adjacent neural structures (i.e., epidural space and intervertebral foramina) and that there is no vascular runoff. At this point, 0.3 mL of 1% to 2% lidocaine should be injected through the needle.

(iv) Cervical Medial Branch Block

The C2-C3 facet joint, the highest cervical facet joint, is innervated mainly by the third occipital nerve, which runs AP across the lateral surface of the C2-C3 facet joint. The medial branches of C3 and C4 dorsal rami innervate the C3-C4 facet joint. Each of these medial branches runs AP hugging the middle point of the articular pillar. The rest of the cervical facet joints have similar innervation to the C3-C4 facet joint from the medial branches at the respective levels.

SPECIAL COMPLICATIONS

Injury and injection into carotid artery and vertebral arteries

Seizure

Damage to brachial plexus

TECHNIQUE.

The multiple-needle technique is described but the single-needle technique also can be used in a similar fashion as for lumbar medial branch blocks.

Patient lies in the lateral position.

PA and lateral view of fluoroscopy is used to identify the cervical articular pillars and facet joints.

A 25-gauge, 1.5-inch spinal needle is used.

The target point for the block is slightly anterior to the midpoint of the C2-C3 facet joint in the lateral view and on the surface of the C2-C3 facet joint in the PA view.

The needle end point for blocking the deeper medial branches of C3 and medial branches of C4 to C7 is at the midpoint of

the pyramid of the articular pillars in lateral view and on the lateral surface of the articular pillar in the PA view. The target point for the C7 medial branch block is high on the apex of the SAP of C7.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree