Key Clinical Questions

What is the prevalence of delirium in hospitalized patient populations?

What are the most common causes of delirium?

Why is it important to detect delirium?

What are the symptoms of delirium?

How is delirium diagnosed?

How can delirium be prevented and treated?

A 56-year-old bank manager with a history of lumbar stenosis and major depression was admitted to the hospital five days ago with cellulitis of the left thigh. He was started empirically on intravenous cefazolin, and his fever (40° Celsius on admission) resolved over 96 hours. During his hospital stay, he was given his home dose of fluoxetine 30 mg daily. During preparation of discharge paperwork the medical team is informed that he is pulling at his intravenous line and threatening to leave against medical advice. Excitedly reaching into the air in front of him, he comments “I’m popping the bubbles.” When no bubbles are observed, what should be the next steps? |

A 73-year-old retired secretary with a history of hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia, was readmitted from an acute rehabilitation facility for failure to thrive. She was discharged from the hospital one week ago, after having recovered uneventfully from a thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair two weeks earlier. Her nurse at the rehabilitation facility informed the medical team that “she was just not motivated to get better—she refused physical therapy and would not eat her meals.” Her daughter reports that “before her surgery she had all her marbles, but now she gets confused about where she is, and sometimes she doesn’t even recognize me.” During family visits she was unusually distractible and drowsy during the day. How should the health care team approach this problem? |

Introduction

Delirium is common in hospitalized patients. The prevalence of delirium may be as high as 80% in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit (ICU), 50% in geriatric postoperative patients, and 10% to 40% in general medical patients. Patients who develop delirium frequently have multiple risk factors. These include nonmodifiable factors, such as increased age, preexisting cognitive impairment, and a history of prior stroke or brain injury. Important modifiable risk factors include (1) exposure to deliriogenic medications, (2) infection, (3) metabolic derangement, (4) organ failure, (5) dehydration, (6) malnutrition, (7) surgery, (8) immobility, (9) use of physical restraints, (10) sensory impairment, (11) sleep deprivation, (12) pain, and (13) drug withdrawal or intoxication.

Delirium as a red flag

|

Delirium is associated with increased mortality, morbidity, and length of stay. Estimates of annual U.S. health care costs attributed to delirium range from $40 billion to $150 billion. Delirious patients require extra care following discharge from acute inpatient units and are at increased risk of being discharged to a skilled nursing facility rather than an acute rehabilitation facility or directly home. Patients often suffer because of frightening memories from delirious episodes while hospitalized. Such experiences can result in appreciable anxiety and preoccupation long after delirium has cleared, significantly impacting the patient’s quality of life for months to years. Family members are often distressed by the changed demeanor and behavior of their loved one, making care and support more challenging.

Pathophysiology

The central feature of delirium is an acute disturbance of consciousness that is accompanied by altered cognition and/or perception. Disruptions in brain function occur in the brainstem, thalamus, prefrontal cortex, fusiform cortex, and parietal lobes. This widespread cortical dysfunction is typically associated with diffuse and symmetric slowing of electrical activity on electroencepholography (EEG), although fast electrical activity occurs in some cases, especially in alcohol or sedative withdrawal.

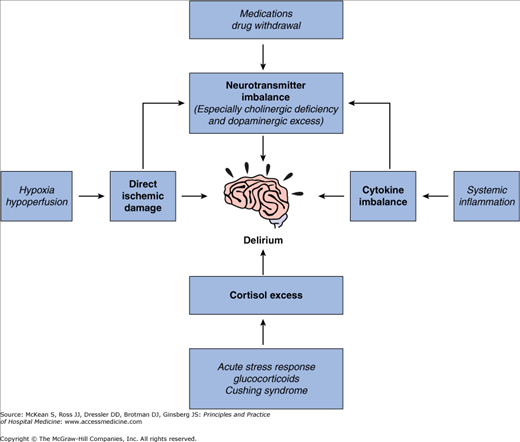

Figure 79-1 depicts numerous potential pathways to delirium and underscores its complex pathogenesis. Neurotransmitter imbalances, especially cholinergic deficiency and dopaminergic excess, may play a key role in the development of delirium. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that anticholinergic and dopaminergic drugs frequently precipitate delirium, whereas antidopaminergic drugs, such as antipsychotics, effectively treat the symptoms of delirium. Other neurotransmitters, such as glutamate, GABA, serotonin, norepinephrine, and histamine, have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of delirium (for example, norepinephrine and glutamate hyperactivity and GABA hypoactivity are associated with delirium tremens, while GABA hyperactivity is associated with hepatic encephalopathy).

All of the following are required:

|

Proinflammatory cytokines have a direct neurotoxic effect on the brain and affect the synthesis and release of neurotransmitters, thereby indirectly contributing to delirium. Finally, elevated cortisol levels and ischemic brain damage from hypoperfusion or hypoxia also have been linked to delirium. For a more detailed discussion see Chapter 26 in Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 17th edition, Maldonado, 2008.

Diagnosis of Delirium

The diagnosis of delirium is based on clinical observation of a relatively abrupt alteration in the level of consciousness, which often waxes and wanes over the course of a day, with associated inattention and changes in cognition and/or perception. Due to inattention, patients may ask the same question repeatedly or perseverate on an answer. Cognitive deficits may affect short-term and intermediate recall, word finding, orientation, and the ability to learn new information. Perceptual disturbances, such as illusions or hallucinations, are also common. Illusions are misinterpretations of stimuli (eg, mistaking an intravenous line for a snake), while hallucinations are perceptions without stimuli. Hallucinations are most frequently visual (eg, seeing bugs crawling on the walls), but can be auditory (eg, hearing voices), or tactile (eg, feeling bugs crawling on the skin). These disturbances arise as physiologic consequences of medical illness or from substance intoxication or withdrawal, rather than from an underlying psychiatric condition.

There are other common features of delirium that are not necessary for the diagnosis but are noteworthy because they often mimic mental illness. Patients may develop fixed, false, idiosyncratic beliefs (delusions), often persecutory in nature. For example, delirious patients commonly believe that their nurses or doctors intend to harm them. Other frequent findings include speech that is difficult to follow or that frequently wanders off topic (disorganized speech). Patients may also experience significant and rapid shifts in emotional tone (affective lability), with bouts of tearfulness, anxiety, or increased irritability. Sleep-wake cycle disruption, with increased napping during the day and difficulty with sustained sleep at night, is common.

Subtypes of delirium are distinguished by the predominant level of psychomotor activity. The hypoactive subtype is characterized by decreased motor activity and increased somnolence. Patients appear quietly indifferent to their surroundings and have great difficulty arousing and sustaining attention. Treating physicians may misattribute this presentation to a depressive disorder. The hyperactive subtype is associated with increased motor activity and agitation. Patients are restless, talkative, and aroused. They may pull at intravenous lines and indwelling catheters or even strike out against caregivers. Although they appear fully alert, these patients have trouble sustaining attention. The mixed subtype includes features of both increased and decreased psychomotor activity. While hyperactive behavior is easy for nurses and doctors to identify, hypoactive delirium is often overlooked because these patients are not demanding, and their cognitive limitations must be elicited through direct examination. To avoid missing hypoactive delirium, physicians must maintain a high index of suspicion and should expect all patients to be easily arousable and able to perform basic cognitive tasks at their preadmission level.

A number of screening tools for delirium have been developed. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a nonspecific but widely used tool that tests cognitive performance. Baseline scores vary widely, so it is most useful when performed upon hospital admission, if a patient is not delirious, and then repeated serially throughout the hospitalization. When using the MMSE, physicians should be aware that highly educated individuals may perform well even when frankly delirious. Examples of more specific screening tools include the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) and the Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98 (DRS-R-98), both of which have been validated in general medical or geriatric populations. For patients in the ICU setting, the CAM-ICU (a modified version of the CAM that can be administered to nonverbal, mechanically ventilated patients) has been demonstrated to be a valid and highly reliable screening tool that is easily administered by ICU nurses. Another validated instrument for the critical care setting is the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC), a cumulative checklist that is completed during each nursing shift over a 24-hour period. Both the CAM-ICU and the ICDSC can be downloaded from the following Web site: http://www.icudelirium.org. Finally, the EEG, which typically reveals diffuse slowing in the setting of delirium (except in delirium tremens, which is associated with fast activity), may help support a diagnosis of delirium or rule out nonconvulsive seizure activity; however, its use as a primary diagnostic tool is not indicated, since it is neither sufficiently sensitive nor specific.

Differential Diagnosis

Physicians frequently misattribute signs and symptoms of delirium to psychiatric illness. For example, distinguishing delirium from dementia can be challenging. Both diagnoses are associated with cognitive impairment. However, dementia without superimposed delirium does not result in waxing and waning levels of consciousness. The patient’s recent baseline physical and mental status, along with timing of onset, pattern of symptom fluctuation, and duration of symptoms will help to distinguish these two syndromes and should be carefully elicited from collateral informants (eg, family, bedside nurse). Delirium is rapid in onset over hours to days, while dementia involves a protracted decline over months to years. “Sundowning,” variably defined in the literature, refers to an increase in confusion and agitation during late afternoon and evening among a subset of patients with dementia. Some authors regard this as a delirium-related phenomenon; however, little systematic research has been conducted, and multiple other etiologies have been proposed (for example, the phenomenon has been explained as a response to fatigue or to unmet physical or psychological needs, or as the consequence of underlying sleep disorders or inadequate light exposure during the day). In practice, it must be remembered that demented patients can also develop delirium. Whenever there is a fluctuating level of consciousness, a workup for delirium should be initiated.

Delirium, especially the hypoactive subtype, is also commonly confused with a depressive illness. Patients with either diagnosis may have significant psychomotor slowing, poor oral intake, and sleep disruption. They may appear withdrawn and sad, and they may even express a desire to die or end their lives. However, depressed patients do not experience alterations in level of consciousness. They may be inattentive and have problems with short-term recall, but they remain oriented. They also frequently have a personal and/or family history of depression and describe a gradual onset of symptoms, in contrast to the acute onset observed with delirium.

A number of other psychiatric disorders also may be misdiagnosed in the delirious patient. Hyperactive delirium may be confused with mania, and prominent hallucinations or delusions frequently raise concern for schizophrenia. Delirious patients who are anxious may be misdiagnosed with anxiety disorders. Moreover, those who are irritable (such that they refuse medical care) or inattentive (such that they fail to follow nursing instructions) may be considered “difficult” or “noncompliant,” even when their behaviors result from delirium and are not within their control. In all these cases, if there is a fluctuating level of consciousness or disorientation, delirium is a more likely diagnosis than any other psychiatric condition. The past psychiatric history and timing of symptom onset are also essential in making a diagnosis. Most psychiatric disorders present by early adulthood, although there are exceptions, such as depressive disorders. Nevertheless, if a geriatric patient is suddenly seeing rats scurrying across the room or is described by family members as “easy-going and slow-to-anger” but is observed to be “difficult,” a new-onset psychiatric disorder is unlikely, and delirium should be high on the differential diagnosis.

Because delirium can masquerade as almost any psychiatric disorder, it is imperative that physicians avoid basing any new psychiatric diagnoses on a patient’s mental status while he or she is still delirious. Even if history obtained from collateral informants suggests that there is an underlying anxiety disorder or major depressive disorder, pharmacologic treatment of these disorders should not be initiated until the patient’s delirium has cleared, since new medications may worsen the delirium and response to a new medication cannot be properly assessed while a patient is still delirious. Physicians should also be wary of attributing psychiatric symptoms to a patient’s known chronic psychiatric illness without thoroughly evaluating whether the symptoms are consistent with that illness. Just as demented patients can become delirious, so can patients with any other psychiatric disorder.

Treatment of Delirium

Delirium is a medically important indicator. It may be the first sign of a new medical condition that is life threatening, such as worsening organ failure, overdose, new infection, or a central nervous system (CNS) event (see Table 79-1 for a list of common causes). The most important goal in treating delirium is to discover and correct the underlying cause(s). Table 79-2 outlines considerations in the work-up of delirium. Start by reviewing the history, doing a physical exam, and performing basic laboratory investigations.

D Drugs/Poisons

|

E External insults

|

L Lesions from cancer

|

I Infections

|

R Remote effects of cancer (paraneoplastic syndromes)

|

| I Ictal/Interictal/Postictal (Seizures) |

V Vascular Causes

|

M Metabolic Causes

|