Links: Definitions & ICD9&10 | Elderly | S/s & W/u | ORT / ORS | Hypodermoclysis / Proctoclycis / Other | IV Solutions | Pediatric | Fluids | Intraosseous infusion | See Fluid Resuscitation for Burns | Dairy & Water |

Dehydration and hypovolemia are different fluid and sodium balance disorders, which may occur concurrently or independently. Dehydration, volume depletion, and hypovolemia often used interchangeably in clinical settings to describe fluid loss.

Dehydration: loss of intracellular water that ultimately causes cellular desiccation and incr’s the plasma Na and osmolality. No circulatory instability, should get 5% Dextrose slowly. Yet most also have volume depletion and need NS (Hypovolemia refers to both conditions). Diarrhea is the #1 cause. Volume loss and dehydration can be inferred from the pt history. Often in the elderly with infections and poor access to water. Historical features include vomiting, diarrhea, fever, adverse working conditions, decreased fluid intake, chronic disease, altered level of consciousness, and reduced urine output. Dehydration in clinical practice refers to the loss of body water, with or without salt, at a rate greater than the body can replace it.

There are 2 types of dehydration: (1) a loss of body water mainly from the intracellular compartments (hyperosmolar, due either to increased sodium or glucose) and (2) volume depletion, referring to a loss of extracellular fluid clinically affecting the vascular tree and interstitial compartment.

Volume Depletion (Hypovolemia): a decreased intravascular blood volume. Often from loss of Na from the extracellular space (intravascular, interstitial fluid) after GI hemorrhage, vomiting, diarrhea, diuresis. Have circulatory instability and need NS rapidly. See Hypovolemia |

Hypertonic/hypernatremic hypovolemia: net extracellular water loss or hypertonic sodium gain. Plasma sodium > 145 mmol/L (145 mEq/L).

Isotonic hypovolemia: loss of sodium proportional to loss of total body water. Plasma sodium 135-145 mmol/L (135-145 mEq/L).

Hyponatremic/hypotonic hypovolemia: net sodium depletion relative to extracellular water. Plasma sodium < 135 mmol/L (135 mEq/L).

The Regulation of Water Metabolism:

Water comprises 55% to 65% of body mass. Two thirds of the water in the body is intracellular, predominantly in lean tissue. Of the remaining one third of body water that is extracellular, only 25% is intravascular, representing a mere 8% of total body water.

Physiological Functions of Water:

• Aqueous environment to allow chemical reactions to occur within cells.

• Waste product removal (urine and feces).

• Aqueous medium for transport of nutrients, gases, and hormones.

• Thermoregulation (sweat).

• Lubricant for joints.

• Shock absorber (intravertebral discs).

ICD-9 Codes:

276.50 Volume depletion NOS

276.51 Dehydration

276.52 Hypovolemia

276.6 Fluid overload / retention

ICD-10 codes:

E87.0 hyperosmolality and hypernatraemia

E86 volume depletion

ICD-10-CA modification in Canada

E86.0 dehydration

E86.8 other volume depletion (hypovolemia)

P74.1 dehydration of newborn

X54 lack of water

Elderly: susceptible as decr thirst sensation & kidney ability, debilitating illness, meds. With aging, there is a decline in total body water, in both the extracellular and intracellular fluid volume (Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:1342–1350). This decline in total body water and the alterations in water regulation with aging leads to increased vulnerability of older persons to heat stress. In response to heat and exercise, older persons tend to lose more intracellular fluid and less interstitial fluid in an attempt to maintain intravascular volume. Water and salt homeostasis are well maintained in the healthy elderly in the absence of stress. With stress they are more vulnerable for several reasons. First, the elderly have a decreased thirst drive, and it takes a larger change in plasma osmolarity to stimulate water intake. Even then, the amount of water ingested is often less than necessary. Even the stress of ischemia or an early infection may be enough to cause an elder to drink or eat less, initiating a cycle that can lead to confusion and even less intake-a cycle that quickly escalates to serious dehydration. Studies show that fluid restriction results in relatively less stimulation of thirst and fluid intake compared to older persons and that heat exposure and exercise are also associated with decreased thirst and fluid intake in older persons (Am J Physiol. 1991;261:R166–R171 and Endocrinol Metab Clin. 2005;34:1–12). Older persons also develop a higher serum osmolality in response to fluid deprivation due to changes in renal function with aging.

S/s: In the elderly, one study identified orthostasis, decreased skin turgor (subclavian and forearm), tachycardia, dry oral mucosa, and recent change in consciousness (delirium) as factors associated with dehydration in the nursing home, however, none of these factors were diagnostic (J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1225–1230). Skin turgor is not reliable because of the loss of subcutaneous tissue with aging.

Consequences of Dehydration: Weight Loss. Constipation. Falls. Delirium. Drug toxicity. Orthostasis. Delayed wound healing Renal failure. Postprandial hypotension. Infections (urine and respiratory). Seizures. Myocardial infarction. Hospitalization. Severe dehydration leads to somnolence, psychosis, unconsciousness and death. Dehydration and infections are major causes of acute confusion in nursing homes (Clinical profile of acute confusion in the long-term care setting. Clin Nurs Res. 2003;12:145–158). Persistent subclinical dehydration is associated with anxiety, panic attacks, and agitation, fluctuation in tissue hydration results in inattention, hallucinations, and delusions (J Am Coll Nutr. 2007;26(5 Suppl):555S–561S).

S/s: Everything must be interpreted in context. Dry axilla & dry MM’s are both unreliable. Tongue furrows can be seen, but mouth breathing can cause this. Cap refill and skin turgor are not good signs in the elderly. Normal elderly may have sunken eyes, tenting (lose elastin fibers with age), tachycardia, concentrated urine and orthostatics. Look for tongue furrows & dryness, upper body weakness, speech difficulties, confusion. Other signs include >5% wt loss in 30d, dizziness, failure to eat, febrile illness, problems with hand dexterity, uncontrolled DM, UTI. Clinical symptoms and signs of dehydration generally have poor sensitivity and specificity. This requires a high index of suspicion to make the diagnosis.

S/s: Everything must be interpreted in context. Dry axilla & dry MM’s are both unreliable. Tongue furrows can be seen, but mouth breathing can cause this. Cap refill and skin turgor are not good signs in the elderly. Normal elderly may have sunken eyes, tenting (lose elastin fibers with age), tachycardia, concentrated urine and orthostatics. Look for tongue furrows & dryness, upper body weakness, speech difficulties, confusion. Other signs include >5% wt loss in 30d, dizziness, failure to eat, febrile illness, problems with hand dexterity, uncontrolled DM, UTI. Clinical symptoms and signs of dehydration generally have poor sensitivity and specificity. This requires a high index of suspicion to make the diagnosis.

• Dry axilla is fairly useful if present, with a positive likelihood ratio of 2.8 (BMJ. 1994;308:1271)….had a sensitivity of 50% and a specificity of 82%.

• The absence of a dry tongue (dry mucous membranes and longitudinal furrows) makes it unlikely that the person is dehydrated, but its presence is not a useful diagnostic clue. Sunken eyes also has a sensitivity of 62%.

• A study in elderly hospitalized veterans found that urine color had a moderate correlation with urine specific gravity (Monitoring hydration status in elderly veterans. Western J Nurs Res. 2002;14:132–142)……urine color had a good correlation with urine specific gravity and dehydration status in residents with adequate renal function (>50 mL/min).

• A study in elderly hospitalized veterans found that urine color had a moderate correlation with urine specific gravity (Monitoring hydration status in elderly veterans. Western J Nurs Res. 2002;14:132–142)……urine color had a good correlation with urine specific gravity and dehydration status in residents with adequate renal function (>50 mL/min).

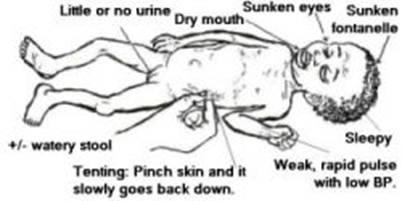

Children: On physical examination, the most helpful individual signs for detecting dehydration in children are prolonged capillary refill time, abnormal skin turgor, and abnormal respiratory pattern.

• Compared with individual signs, however, clinical dehydration scales based on a combination of physical examination findings are more specific and sensitive for accurate diagnosis of dehydration in children, and they are also useful for categorizing the severity of dehydration (Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:692-696)……Four factors that most reliably predicted dehydration in 1 study were capillary refill time exceeding 2 seconds, absence of tears, dry mucous membranes, and general appearance suggesting acute illness. When at least 2 of these signs are present, fluid deficit is likely to be 5% or more. Another validated scale in children with acute gastroenteritis suggested that general appearance, degree of sunken eyes, mucous membrane dryness, and lack of tear production were associated with length of hospital stay and the need for intravenous fluids.

• The ratio of the diameters of the inferior vena cava to the aorta might be helpful in identifying dehydration in children with gastroenteritis (Acad Emerg Med 2010;17:1042)…..At a cutoff of <0.8, the IVC:aorta ratio yielded a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 56% for identifying significant dehydration as well as a positive predictive value of 56% and a negative predictive value of 86%. Physician assessment of dehydration alone was 78% sensitive and 51% specific for identifying significant dehydration. Interrater reliability for ultrasound measurements was good (Pearson correlation coefficient, 0.76).

Labs: Check lytes for incr Na & BUN. Yet BUN not reliable as both starvation & liver dysfunction prevent its rising commensurate with volume loss. Measure serum Osm & urine Na. A Ur S.G. >1.020 is dehydrated. Elevated osmolality, considered to be elevated when it is greater than 300 mmol/kg. Between 295 and 300 can be considered to suggest impending dehydration. In all cases, either serum sodium or glucose levels must be elevated. When both water and salt are lost, dehydration is associated with hyponatremia and low osmolality. The majority of these patients will have a metabolic alkalosis and elevated BUN/creatinine ratio and uric acid. Urine sodium levels may be low or increased.

Urine output <2ml/kg/hr is oliguria. Each kg BW loss is ~1L deficit.

Adults–> check bicarb & BUN/Cr ratio (>25 suggests dehydration or renovascular dz). Stool specimens on need if bloody stool or signs of invasive bacteria (abrupt onset, diarrhea precedes vomiting). Screen with FWBC test (incr in bacterial).

Ddx of Elevated BUN/Creatinine Ratio: Dehydration. Renal failure. Bleeding. Congestive heart failure. Sarcopenia (muscle loss). Increased protein intake. Glucocorticoids. Licorice

Dx: Any person suspected of being dehydrated needs at a minimum to have BUN, Na, Cr, glucose, and bicarbonate measured. In addition, osmolality should either be directly measured or calculated. If the sodium is elevated, it is likely that the person has water loss dehydration and needs free water, usually in the form of a 5% dextrose solution. An elevated osmolality in the presence of hyponatremia and elevated glucose suggests a hyperosmolar state due to hyperglycemia. Pseudohyponatremia may be due to hypertriglyceridemia or mannitol infusion and is treated with free water and insulin. If the person is hyponatremic and hyposmolar, and uric acid is elevated in the presence of a metabolic alkalosis, salt loss dehydration is likely presented, provided the person is not fluid overloaded. This condition of dehydration can be effectively treated with isotonic saline.

Tx: See ORT / ORS | Two phases: rehydration and maintenance. In the rehydration phase, the fluid deficit is replaced quickly (i.e., during 3–4 hours) and clinical hydration is attained. In the maintenance phase, maintenance calories and fluids are administered. Rapid realimentation should follow rapid rehydration, with a goal of quickly returning the pt to an age-appropriate unrestricted diet, including solids. Gut rest is not indicated. Breast-feeding should be continued at all times, even during the initial rehydration phases. The diet should be increased as soon as tolerated to compensate for lost caloric intake during the acute illness. Lactose restriction is usually not necessary in children (although it might be helpful in cases of diarrhea among malnourished children or among children with a severe enteropathy), and changes in formula usually are unnecessary. Full-strength formula usually is tolerated and allows for a more rapid return to full energy intake. During both phases, fluid losses from vomiting and diarrhea are replaced in an ongoing manner. Antidiarrheal medications are not recommended for infants and children.

Clinical recommendations for Dehydration in Children: (Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:692-696)

* Children should be evaluated for severity of dehydration as determined by physical examination findings (level of evidence, C).

* For mild to moderate dehydration in children, ORT is the preferred treatment (level of evidence, C).

* Electrolyte disturbances in children resulting from gastroenteritis may be corrected and prevented by use of an appropriate ORT solution (level of evidence, C).

* For children with dehydration, a single dose of ondansetron may facilitate ORT by reducing the incidence and frequency of vomiting, thereby avoiding the need for intravenous fluid therapy (level of evidence, B).

Complications in Children: hypernatremia, hyponatremia, and hypoglycemia. Children with severe dehydration and those with atypical presentations of moderate dehydration should undergo measurement of serum electrolyte levels (Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:692-696)…..Hypoglycemia (blood glucose levels < 60 mg/dL [3.33 mmol/L]) has been reported in 1 study in 9% of children younger than 9 years (mean age, 18 months) who were hospitalized with diarrhea. Because history and physical examination findings were not suggestive of hypoglycemia in these children, blood glucose screening may be indicated for toddlers with diarrhea.

Prevention of Dehydration: Ongoing educational focus on dehydration. Increase awareness of factors responsible for dehydration, eg, fever, hot weather, vomiting and diarrhea, medications. Report decreased intake and dark urine. Provide straws and cups that residents can use. Offer fluids regularly. Provide preferred beverages. Use swallowing exercises and cuing before thickening liquids. Encourage persons with urinary incontinence not to restrict fluids. Hydration cart. Use frozen juice bars. Encourage family involvement in increasing fluid intake

Oral Rehydration Therapy (ORT) (Solution, ORS):

Best if started at the onset of any diarrhea to prevent dehydration. Tx with ORS is simple and enables management of uncomplicated cases of diarrhea at home, regardless of etiologic agent. As long as caregivers are instructed properly regarding signs of dehydration or are able to determine when children appear markedly ill or appear not to be responding to tx, therapy should begin at home. Early intervention can reduce such complications as dehydration and malnutrition. Early administration of ORS leads to fewer office, clinic, and emergency department visits and to potentially fewer hospitalizations and deaths. All families should be encouraged to have a supply of ORS in the home at all times and to start therapy with a commercially available ORS product as soon as diarrhea begins. Although producing a homemade solution with appropriate concentrations of glucose and sodium is possible, serious errors can occur; thus, standard commercial oral rehydration preparations should be recommended where they are readily available and attainable.

Advantages: less $ than IV, less complications than IV, can be used at home.

• Compared with children with gastroenteritis who received IV rehydration, children who received enteral rehydration had significantly briefer hospital stays (mean, 21 hours) with a similar duration of diarrhea and weight gain at discharge (Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004;158:483-90).

• Children moderately dehydrated due to gastroenteritis are better treated in the emergency department with oral (Pedialyte, 50-75 mL/kg over 4hrs) rather than IV rehydration (two 20-mL/kg boluses followed by oral fluids), according a randomized study (Pediatrics. 2005;115:295-301). 50% of both the ORT and IVF groups had successful rehydration at 4 hours, defined as resolution of moderate dehydration, production of urine, weight gain, and the absence of severe emesis >5 mL/kg. Hospitalization was needed in <31% of the ORT group Vs 49% of the IVF group.

Contra: Contraindications to use of ORT: altered mental status with risk for aspiration, abdominal ileus, and underlying intestinal malabsorption. Treatment goals for oral rehydration are to restore circulating blood volume and interstitial fluid volume while maintaining adequate rehydration. A normal, age-appropriate diet should be started once rehydration is achieved. Severe dehydration, shock, intractable vomiting, lack of personnel to administer ORT. Need 75-90mEq/L of Na. 2-2.5g/dL glucose (High glucose content in soda & juices –> incr osmolality–> osmotic diarrhea.), 300-330 mOsm/L.

Dose: Children with moderate dehydration should receive 100 mL of ORT solution per kg body weight, given for 4 hours in the physician’s office or emergency department. A simplified method to provide maintenance ORT at home, based on average weights of infants and children, is derived from the Holliday-Segar method: 1 oz per hour for infants, 2 oz per hour for toddlers, and 3 oz per hour for older children. In addition, children should receive 10 mL/kg for every loose stool and 2 mL/kg for every episode of emesis.

Approximate Amount of ORS by Age in First 4 Hours (per WHO):

Age –> ORS Volume

< 4 months –> 200-400 mL.

4-11 months –> 400-600 mL.

12-23 months –> 600-800 mL.

2-4 years –> 800-1,200 mL.

5-14 years –> 1,200-2,200 mL.

e 15 years –> 2,200-4,000 mL.

Reduced-Osmolarity WHO Formula (2002):

Reduced osmolarity ORS preserves the 1:1 molar ratio of sodium and glucose and provides a lower osmolar load on the intestines. These features result in better water absorption, comparable sodium absorption, and lower diarrheal volume compared with the previously administered iso-osmotic solutions.

Glucose @ 75 mmol/L, Na @ 75 mEq/L, potassium @ 20 mEq/L, Cl @ 65 mEq/L, citrate @ 10 mmol/L, osmolarity @ 245 mOsm/L = mmol/L. Contains 17% less sodium, superior to standard ORS in the management of diarrheal diseases in children (except cholera) (JAMA 2004;291:2628-35). The reduced osmolarity oral ORS now recommended by the WHO for dehydrating diarrheal disease is not associated with an increased risk for hyponatremia (JAMA. 2006;296:567-573) (50% lower incidence of symptomatic hyponatremia vs higher osmolarity OSR).

The standard WHO ORS (1975): contains 90 mmol/L of Na, 111 mmol/L glucose (total osmolarity = 311 mmol/L), this is critical for areas where cholera is common, a reduced osmolarity ORS can be used in other places (BJM 2001;328:81). Also has potassium @ 20 mEq/L, Cl @ 80 mEq/L, citrate @ 10 mmol/L. Still ok for use in complicated diarrhea, not for mild-moderate dehydration (use the reduced Osm).

Dietary Adjustments: incr salt with boiled starches, boiled vegetables, soups, yogurt, bananas, avoid Lactose until formed stools developed.

Rehydralyte or WHO Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS) formula and :

Home ORS Formulas:

May be given by bottle, cup, spoon, syringe, or NGT. Give frequent small amounts, ~10ml q 10min, can incr rate by 5ml q min at tolerated. To prevent dehydration, suggest 2 to 4 oz (60-120ml) of a rehydrating solution for children <22 pounds (10kg) or 4 to 8 oz (120-240ml) for heavier kids for each episode of vomiting or diarrhea. 1 teaspoon (tsp) = 5 mL.

Formulation #1: The “simple solution”: 1 level tsp salt + 8 level tps sugar (avoid artificial sweeteners) + 1 L(or 5 cupfuls, each 200 mL) of clean drinking or boiled water. Stir the mixture till the salt and sugar dissolve. Store the liquid in a cool place. Chilling the oral rehydration solution may help. If the child still needs oral rehydration solution after 24 hours, make a fresh solution.

Formulation #2: 1/4 tsp salt + 1/4 tsp baking soda or bicarbonate of soda (If baking soda is not available, add another 1/4 tsp of salt). 2 tbsp sugar or honey + 1lL (1000 mL or 5 cupfuls, each 200 mL) of clean drinking or boiled water. Stir the mixture till the salt and sugar dissolve.

Formulation #3: ¾-1 level tsp (3.5g) salt + ½-1 tsp baking soda + 8oz water (or OJ) + 4 level tsp sugar + 4 tsp Cream of Tartar (KCl, K bitartrate). Can replace the sugar with 50-60g of cereal flour or 200g mashed potatoes to make a food-based formula.

Or 1 qt (1L) water + ¾ tsp salt substitute (KCl) + ½ tsp Baking soda + 3 Tbs Karo Syrup (White Corn Syrup) + 1 packet unsweetened powdered drink mix (Kool-Aid) or fruit juice concentrate.

Or 8oz (240ml) fruit beverage (OJ, apple) + 8 oz water + ½ tsp honey/ corn syrup + pinch NaCl + ¼ tsp baking soda. Carb-Na ratio of <2:1.

Or (8:1 sugar:salt): 2 tsp sugar + ¼ tsp salt + squeeze lime in 8oz water.

Or WHO Formula: 3.5g NaCl + 2.5g Na-bicarb (or 2.9g Na-citrate) + 1.5g KCl + 20g glucose (or 40g sucrose) + 1 liter of water. Any pharmacist can prepare this.

Commercial Products: Children preferred Pedialyte and Pediatric Electrolyte (both contain sucralose) to Enfalyte (contains rice syrup solid) according to a blinded crossover study from a Toronto emergency department with 66 children (age range, 5–10 years) (Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010;164:696)…..Most children identified Pedialyte as the best-tasting solution (53%), followed by Pediatric Electrolyte (39%) and Enfalyte (8%).

CeraLyte: rice bases, OTC. Comes in a powder in 2 sodium strengths (50 and 70 mEq/L) or a liquid at 50 mEq/L sodium.

Info: www.rehydrate.org

Pt Instructions:

Step #1: Wash hands with soap and water before preparing solution.

Step #2: Prepare a solution, in a clean pot, by mixing: 1 liter of clean drinking or boiled water (after cooled) with one teaspoon salt and 8 teaspoons sugar or 1 packet of ORS. Stir the mixture till all the contents dissolve.

Volume given: In general, 50 mL/kg (mild dehydration) to 100 mL/kg (moderate dehydration) of body weight is slowly administered over a 2 to 4 hour period. Alternatively, 1 mL of fluid should be administered for each gram of output. In hospital settings, soiled diapers can be weighed (without urine), and the estimated dry weight of the diaper can be subtracted. At home, however, this is impractical. Consequently, 10 mL/kg of body weight (2 tsps/kg) of fluid can be given for each watery stool or 2 mL/kg body weight for each episode of emesis. Another possible method of fluid replacement is in children weighing <10 kg (22lb) to administer 60-120 mL (2-4 oz) of an ORS for each episode of vomiting or diarrheal stool. For children weighing >10 kg, 120 to 240 mL (4-8 oz) of solution is administered for each episode of vomiting or diarrheal stool.

Step #3: Wash your hands and the baby’s hands with soap and water before feeding solution. Give the sick child as much of the solution as it needs, in small amounts frequently. Ok to give child alternately other fluids – such as breast milk and juices. Continue to give solids if child is four mo’s or older. If the child still needs ORS after 24 hours, make a fresh solution. Remind them that ORS does not stop diarrhea, but it prevents the body from drying up (the diarrhea will stop by itself). If child vomits, wait ten minutes and give it ORS again. Usually vomiting will stop. If diarrhea increases and /or vomiting persists, take child over to a health clinic.

Other solutions that are suitable drinks to prevent a child from losing too much liquid during diarrhea: Breast-milk. Gruels (diluted mixtures of cooked cereals and water). Carrot Soup. Rice water. If possible, add 1/2 cup orange juice or some mashed banana to improve the taste and provide some potassium. Molasses and other forms of raw sugar can be used instead of white sugar, and these contain more potassium than white sugar. If none of these drinks is available, other alternatives are: Fresh fruit juice. Weak tea. Green coconut water. If nothing else is available, give water from the cleanest possible source (if possible brought to the boil and then cooled).

Contact their healthcare provider if: infants <6 months or 18 pounds. History of chronic medical conditions or prematurity. Visible blood in stool. Fever >38°C (100.4°F) if child <3 mo. Fever >39°C (102.2°F) if child >3 mo. Frequent, high volume stools. Persistent vomiting. Sx’s of more severe dehydration such as sunken eyes, decreased urine output, dry mucous membranes. Changes in mental status. Lack of response or inability to take oral rehydration solutions.

***Ref: (Oral rehydration therapy. Prescriber’s Letter 2007;23(4):230413) (Oral rehydration therapy in children with acute gastroenteritis. JAAPA 2005;18:24-9) (Oral versus intravenous rehydration for treating dehydration due to gastroenteritis in children. Medscape 2006. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/542075)

Comparison of the Composition of Solutions:

Solution –> Na (mEq/L)\ K (mEq/L)\ Cl (mEq/L)\ Bicarb (mEq/L)\ Glucose (g/dL):

ECF –>142\4\103\27\0.1.

LR –> 130\0\109\28\0.

0.9% NaCl ( NS) –> 154\0\154\0\0.

Chicken Broth –> 250\5-8\-\-\-.

WHO-ORS –> 90\20\80\-\2.

Pedialyte –> 45\20\35\30\2.5.

Gatorade –> 28\2\-\-\2.1.

Ginger Ale –> 4\0.2\-\-\9.

Coke/Pepsi –> 2.5\0.5\9\10\10.5.

Apple Juice –> 3\17\-\-\12.

Grape Juice –> 3\25\-\-\15.

Jell-O –> 24\1.5\-\-\16.