Definition and classification of chronic pain

Introduction

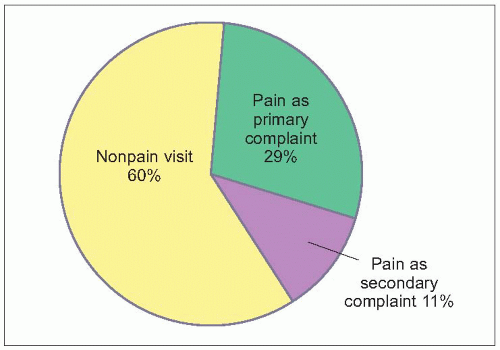

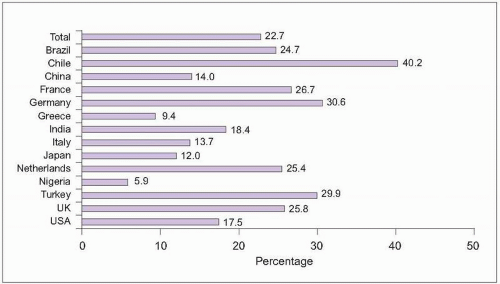

Chronic pain is one of the most common conditions seen in primary care practices, accounting for 40% of office visits (1.1)1. Data from the World Health Organization identified the worldwide prevalence of significant, persistent pain at about 23% (1.2)2. The three most common pain locations were back pain (53%), headache (48%), and joint pain (46%). When re-evaluated after 12 months, pain complaints persisted in 49% of patients with baseline pain worldwide. In addition, 70% of persistent pain patients are managed by their primary care physician, while only 2% see a pain management specialist3.

1.2 This survey of primary care patients in 14 countries identified the prevalence of persistent pain, defined as pain occurring on most days for at least 6 months. The pain also needed to be significant enough to result in presentation to a healthcare provider, use of medication, or significant interference with activities. (Based on Gureje O, et al., 20012.) |

Case presentation

A 53-year-old hospital custodian/caretaker complained of low back pain shooting down his left leg after completing a typical day of work. Neurological evaluation showed marked muscle spasm of the paravertebral muscles, extreme pain with straight leg raise testing, and numbness over the lateral left calf. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan confirmed the clinical suspicion of an L5 radiculopathy from a pinched nerve in the spine. Failing to get relief from conservative treatment of bed rest, steroids, and analgesics, he underwent uncomplicated surgical discectomy. Postoperatively, straight leg raise testing normalized and numbness resolved. The patient, however, continued to report persistent, disabling pain at visits 3 and 6 months after surgery. Repeat MRI scan showed good relief of previous neural compression. One year postoperatively, he had still not returned to work and was seeking permanent disability.

This patient typifies many features of chronic pain, which often persists despite seemingly successful correction of underlying pathology and healing. Medical staff, family members, and even patients sometimes begin to wonder if their pain complaints can be real when physical examinations, X-rays, MRI scans, and other tests fail to reveal any ongoing pathology. Through careful investigations with animal models of pain, researchers have demonstrated the physiological basis of persistent, chronic pain.

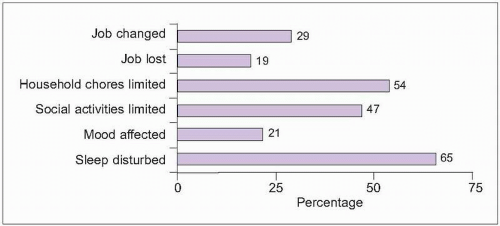

1.3 Impact of chronic pain. A community-based survey of people in 15 European countries and Israel identified at least moderately severe chronic pain lasting at least 6 months in 19%. Among those who were employed full- or part-time, nearly one in three changed their job or job duties due to pain, while one in five lost a job. Nearly half of all people with chronic pain reported disturbances in household and social activities. One in five reported developing depression and the majority had disturbed sleep. (Based on Breivik H, et al., 20063.) |

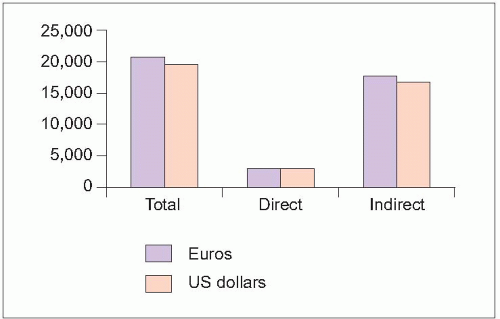

Persistent pain often leads to functional disturbance, depression, and sleep impairment (1.3). A survey of people with at least moderately severe chronic pain in Europe and Israel found that, on average, 7.8 work days were lost during the preceding 6 months due to pain3. Economic costs are also substantial for chronic pain patients (1.4)4.

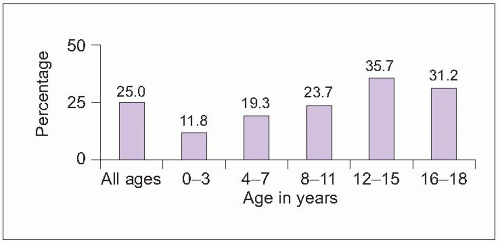

Chronic pain is also common and related to significant impact in pediatric patients. A survey of children aged 0-18 in the Netherlands identified chronic pain in 25%, with pain occurring more frequently in older children and adolescents (1.5)5. About one in three children with chronic pain have very frequent and intense pain5. Children having frequent pain are more likely to miss school more often than children with infrequent pain (41% vs. 14%, P<0.001)6. The most common pain areas reported in children and adolescents are: head, abdomen, limbs, and back7. Chronic pain in children persists for 1 year in 48% and for 2 years in 30%8. Costs are also high for children with pain. In a European study, mean 12-month costs for adolescent pain were £8,027 (over $13,000) (£4,431 in direct costs and £3,596 in indirect costs, including £600 for additional educational services)9.

Despite the important impact and disability associated with chronic pain, patients often believe that their doctors are uninterested in addressing pain complaints (Table 1.1). About one in three people with chronic pain are not currently receiving treatment, often due to perceptions that their healthcare providers cannot help, they should just live with their pain, or treatments will not be tolerated3.

1.4 Annual per-patient costs from chronic low back pain. Annual 2002 costs for chronic low back pain were estimated by evaluating patients in 14 centres in Sweden. The majority of pain-related costs were indirect, with work absence having the major impact. About 60% of employed patients with low back pain missed at least 1 day of work during the preceding 3 months, with an average work loss of 33 out of 60 possible work days. (Based on Ekman M, et al., 20054.) |

1.5 Chronic pain (pain for >3 months) prevalence in children and adolescents. (Based on Perquin CW, et al., 20005.) |

Definition of acute versus chronic pain

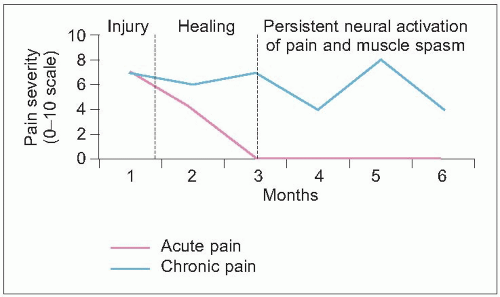

Daily life frequently results in experiences of mild pain – stubbing a toe, twisting an ankle, bumping the ‘funny bone’. These episodes of new-onset pain are termed acute pain. In most cases, acute pain resolves quickly. With more severe injuries, acute pain can persist for several months, resolving during the healing process. The duration of healing depends on the amount of blood flow to various tissues (Table 1.2). After an injury without an ongoing degenerative condition, healing is expected to be completed within 3 months. When pain persists beyond the time of healing or longer than 3 months, this is termed chronic pain (1.6)10. Chronic pain can continue without the occurrence of ongoing degenerative illness or additional injury.

Table 1.1 Percentage of patients reporting beliefs about doctors’ attitudes toward chronic pain | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

Table 1.2 Time to achieve normal healing | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1.6 Acute versus chronic pain. Pain often occurs with trauma or illness, generally decreasing during the period of healing. Acute pain usually resolves within 3 months. Chronic pain persists after healing is completed, due to continued activation of neural pain pathways and muscle spasm. (Based on Marcus DA, 200510.) |

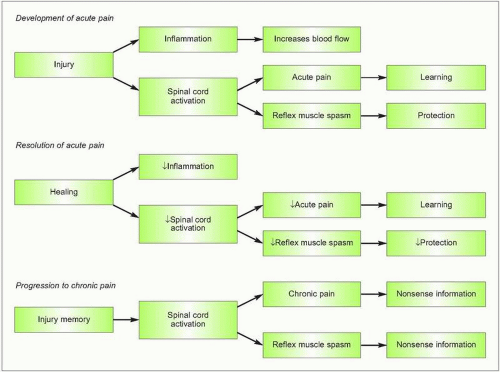

1.7 Physiology of acute and chronic pain. Acute pain is associated with inflammation that brings repair cells to the site of injury and activation of spinal pathways that send instructive pain messages to encourage future injury avoidance and provide protective muscle spasm, like a natural splint. During the subsequent weeks or months of healing, inflammation typically resolves and fewer impulses are sent from the spine to register as pain or trigger muscle spasm. When pain persists beyond the period of healing, the memory of the initial injury results in persistent neural messages for pain and muscle spasm. (Based on Marcus DA, 200510.) |

Acute pain is an important experience, motivating the injured person to rest and recuperate during the critical healing period. Increased blood flow and protective muscle spasm assist in speeding recovery. Acute pain also provides learning opportunities so that future injury can be avoided (1.7). In some cases, pain persists after healing is completed. This persistent or chronic pain provides patients with false signals about injury and encourages excessive activity restriction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree