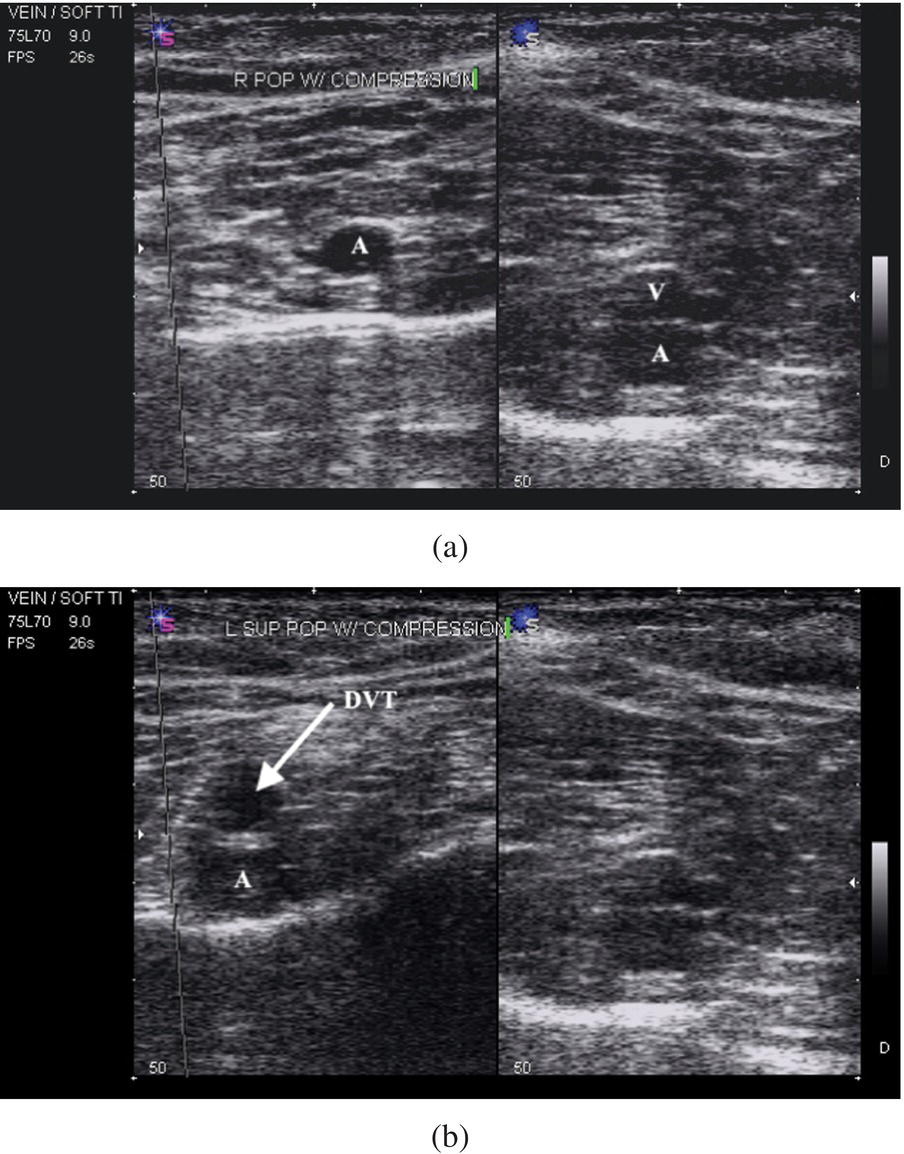

Ali S. Raja1 and Jesse M. Pines2,3 1 Department of Emergency Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA 2 US Acute Care Solutions, Canton, OH, USA 3 Department of Emergency Medicine, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA Deep‐vein thrombosis (DVT) is a blood clot within the deep veins. It commonly occurs in the legs but can also form in the upper extremity, mesenteric, and cerebral veins. Similar to pulmonary embolism (PE), DVT is part of the venous thromboembolism (VTE) disorders.1 Mortality from upper and lower extremity DVT occurs when a DVT breaks free and causes PE, which can lead to sudden cardiovascular collapse and other morbidity. While a diagnosis of DVT is commonly considered in the ED when patients have leg swelling, calf pain, or other symptoms, they are often “silent” and are often diagnosed at autopsy. This makes the incidence of DVT difficult to estimate. The annual incidence of DVT has been estimated at 80 in 100,000 with a prevalence of leg DVT being significantly higher at 1 in 1000.2,3 In the United States, greater than 200,000 people develop DVTs every year, with 1 in 4 cases also causing PE.4 Both DVT as well as PE are common and often “silent” and thus go undiagnosed or are only picked up at autopsy. Therefore, the incidence and prevalence are often underestimated. It is thought the annual incidence of DVT is 80 cases per 100,000, with a prevalence of lower limb DVT of 1 case per 1000 population. Annually in the United States, more than 200,000 people develop venous thrombosis; of those, 50,000 cases are complicated by PE. DVT is relatively rare in children and young adults; at the age of 40, the risk of DVT increases with age. Common conditions associated with DVT include cancer, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and postsurgical patients.5 Accurate and timely identification of patients with DVT can minimize complications and morbidity. However, like PE, DVT is a relatively rare disease, which is often suspected but infrequently diagnosed. In the United States, approximately 1 in every 1000 ED visits results in the diagnosis of DVT.6 As with PE, the challenge in diagnosing DVT in the ED is the appropriate selection of patients for diagnostic testing and risk stratification based on clinical findings. Venous noncompressibility on ultrasound is the major diagnostic criterion for DVT. Compression ultrasound, however, is not specific or sensitive for detecting DVT in patients with asymptomatic proximal DVT or in patients with DVT in the calf.7 It also demonstrates limited accuracy in cases of chronic DVT. The use of ultrasound is further limited in patients who are obese or who have edema.8,9 However, despite these limitations, leg compression ultrasound is often used to detect DVT in the ED. Traditionally, only the proximal veins (from the femoral veins down to the calf, where they join the popliteal veins) are studied. While approximately 50% of DVTs begin in the calf,10 more than 70% of symptomatic DVTs involve the popliteal vein and more proximal leg veins.11 In patients with calf DVTs that may not be detected on the first ED ultrasound, about 20% will extend more proximally within about a week. As DVTs that do not extend above the calf very rarely cause PE, proximal DVTs are at much higher risk for propagation and for causing PE. How sensitive is ultrasound for the detection of DVT? A recent systematic review and meta‐analysis by Bhatt et al. reviewed the accuracy of several diagnostic tests for the diagnosis of DVT. A total of 43 studies met inclusion criteria and were reviewed by the authors, and included analyses of proximal compression ultrasound (Figure 51.1), whole leg ultrasound and serial ultrasound (defined as a diagnostic strategy involving a repeat ultrasound for patients with initial negative ultrasound).12 Either venography or clinical follow‐up were acceptable as reference standards, and studies of both inpatients and outpatients were included. Figure 51.1 Compression ultrasound of the right and left popliteal vessels. (a) The screen is split to show the noncompressed normal anatomy on the right‐hand side and the compressed anatomy of the left‐hand side. (b) The left popliteal vein is noncompressible and represents a deep vein thrombosis. Note: A = artery; and V = vein. (Courtesy of Anthony J. Dean, MD.) Proximal compression ultrasound, which is the test most commonly used in the ED, typically involves evaluation of the trifurcation of the popliteal vein and more proximal veins. It was evaluated in 13 studies that included a total of 4036 patients. Overall, it had a pooled sensitivity of 90.1% (CI 86.5–92.8%) and a specificity of 98.5% (CI 97.6–99.1%) for the diagnosis of DVT.12 In contrast to proximal compression ultrasound, whole‐leg ultrasound evaluates the entire length of the leg veins, including the calf. There were fewer studies that included data on whole‐leg ultrasound; a total of 10 studies included 1725 patients. The pooled sensitivity for whole‐leg ultrasound was 94.0% (CI 91.3–95.9%), with a pooled specificity of 97.3% (CI 94.8–98.6%).

Chapter 51

Deep Vein Thrombosis

Background

Clinical question

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree