CHAPTER 163

Cutaneous Abscess or Pustule

Presentation

A patient with an abscess may or may not have a history of minor trauma (such as an embedded foreign body or a small skin puncture) but has localized pain, swelling, and redness of the skin. The area is tender, warm, firm, and usually fluctuant to palpation. Sometimes there is surrounding cellulitis or lymphangitis and, in the more serious case, fever. There may be a spot where the abscess is close to the skin surface (“pointing”), where the skin is thinned, and pus may eventually break through to drain spontaneously. With the advent of community-acquired methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA), there may be a central or underlying darkened necrotic area, with the patient falsely assuming that he has a “spider bite.” These abscesses generally are extremely tender and inflamed.

A pustule will appear only as a cloudy tender vesicle surrounded by some redness and induration, and occasionally, it will be the source of ascending lymphangitis.

What To Do:

A history and physical examination should include inquiries about immunocompromise, artificial joints or heart valves, valvular heart disease, previous occurrence of similar abscesses, and close contact with people having similar lesions, as well as evidence of systemic symptoms, such as fever and tachycardia.

A history and physical examination should include inquiries about immunocompromise, artificial joints or heart valves, valvular heart disease, previous occurrence of similar abscesses, and close contact with people having similar lesions, as well as evidence of systemic symptoms, such as fever and tachycardia.

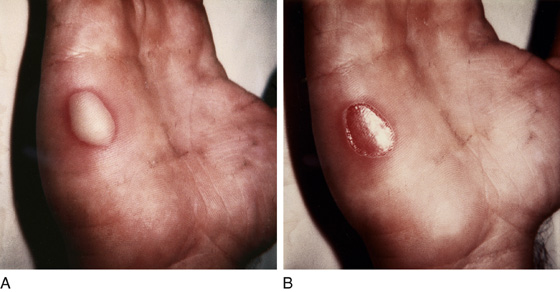

A pustule should not require any anesthesia for drainage. Very small pustules can be opened or unroofed using an 18-gauge needle. For larger pustules, simply snip open the cutaneous roof with fine scissors or an inverted No. 11 scalpel blade, grasp an edge with pickups, and excise the entire overlying surface (Figure 163-1). Cleanse the open surface with normal saline and cover it with ointment and a dressing. The patient should be instructed to use warm compresses or soapy soaks at home.

A pustule should not require any anesthesia for drainage. Very small pustules can be opened or unroofed using an 18-gauge needle. For larger pustules, simply snip open the cutaneous roof with fine scissors or an inverted No. 11 scalpel blade, grasp an edge with pickups, and excise the entire overlying surface (Figure 163-1). Cleanse the open surface with normal saline and cover it with ointment and a dressing. The patient should be instructed to use warm compresses or soapy soaks at home.

Figure 163-1 A, Large pustule before débridement. Local anesthesia is not required. B, Pustule after débridement and cleansing.

When a simple abscess is suspected but the location of the abscess cavity is uncertain, the clinician can attempt to locate it using ultrasonography or by trying to aspirate pus from the cavity with a No. 18-gauge needle after preparing the area with povidone-iodine. When using ultrasonography, if practical, placing the suspected abscess site in a water bath (you can use a bedpan filled with water) will eliminate the need for ultrasound gel or contact between the ultrasound transducer and the patient’s skin, thus eliminating discomfort. If an abscess cavity cannot be located, release the patient on antibiotics and intermittent warm, moist compresses. Have him seen in 24 hours to again check for abscess cavity formation.

When a simple abscess is suspected but the location of the abscess cavity is uncertain, the clinician can attempt to locate it using ultrasonography or by trying to aspirate pus from the cavity with a No. 18-gauge needle after preparing the area with povidone-iodine. When using ultrasonography, if practical, placing the suspected abscess site in a water bath (you can use a bedpan filled with water) will eliminate the need for ultrasound gel or contact between the ultrasound transducer and the patient’s skin, thus eliminating discomfort. If an abscess cavity cannot be located, release the patient on antibiotics and intermittent warm, moist compresses. Have him seen in 24 hours to again check for abscess cavity formation.

In patients who are immunocompromised, have valvular heart disease, or have artificial heart valves or joints, administer empirical antibiotic prophylaxis before performing an incision and drainage (I&D). (See upcoming text for antibiotic choices.)

In patients who are immunocompromised, have valvular heart disease, or have artificial heart valves or joints, administer empirical antibiotic prophylaxis before performing an incision and drainage (I&D). (See upcoming text for antibiotic choices.)

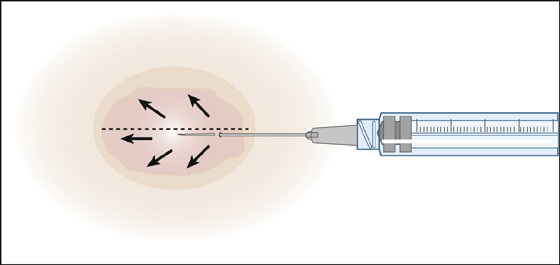

When the abscess is small with a thin roof or is beginning to point, prepare the overlying skin for incision and drainage with povidone-iodine solution. Inject lidocaine superficially into the roof of the abscess along the line of the projected incision (Figure 163-2).

When the abscess is small with a thin roof or is beginning to point, prepare the overlying skin for incision and drainage with povidone-iodine solution. Inject lidocaine superficially into the roof of the abscess along the line of the projected incision (Figure 163-2).

Figure 163-2 Anesthetizing the incision site of a small abscess. The anesthetic is injected in the subcutaneous plane under the area of the planned incision. (Adapted from Singer AJ, Hollander JE: Lacerations and acute wounds. Philadelphia, 2003, FA Davis.)

Incise with a No. 11 or 15 scalpel blade at the most dependent and thin-roofed area of fluctuance. The incision should be large but directed along the relaxed skin-tension lines to reduce future scarring.

Incise with a No. 11 or 15 scalpel blade at the most dependent and thin-roofed area of fluctuance. The incision should be large but directed along the relaxed skin-tension lines to reduce future scarring.

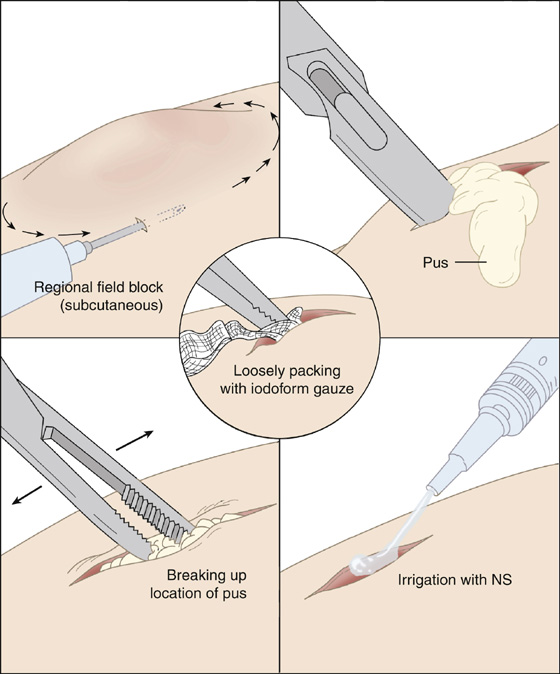

In larger, more complex abscesses, provide systemic analgesia or procedural sedation (see Appendix E). In addition to infiltration across the dome of the abscess, perform a field block by injecting a ring of subcutaneous 1% lidocaine around the abscess, approximately 1 cm peripheral to the erythematous border. As previously, an incision is made across the entire length of the fluctuant area. A hemostat may then be inserted into the cavity to break up any loculated collections of pus. The cavity may be gently irrigated with normal saline and, when deep or expansive, loosely packed with iodoform or plain gauze (Figure 163-3). Leave a small wick of this gauze protruding through the incision to allow continued drainage and easy removal after 48 hours. Some authors have suggested that packing a wound is superfluous, but this should be decided on a case-by-case basis. The practitioner should at least be aware that the purpose of packing is to keep a wound open and that a small amount of gauze suffices. Overpacking an abscess is both painful and counterproductive; it fails to allow the wound to drain. In addition, iodoform gauze may cause the patient excessive pain.

In larger, more complex abscesses, provide systemic analgesia or procedural sedation (see Appendix E). In addition to infiltration across the dome of the abscess, perform a field block by injecting a ring of subcutaneous 1% lidocaine around the abscess, approximately 1 cm peripheral to the erythematous border. As previously, an incision is made across the entire length of the fluctuant area. A hemostat may then be inserted into the cavity to break up any loculated collections of pus. The cavity may be gently irrigated with normal saline and, when deep or expansive, loosely packed with iodoform or plain gauze (Figure 163-3). Leave a small wick of this gauze protruding through the incision to allow continued drainage and easy removal after 48 hours. Some authors have suggested that packing a wound is superfluous, but this should be decided on a case-by-case basis. The practitioner should at least be aware that the purpose of packing is to keep a wound open and that a small amount of gauze suffices. Overpacking an abscess is both painful and counterproductive; it fails to allow the wound to drain. In addition, iodoform gauze may cause the patient excessive pain.

Figure 163-3 Abscess drainage procedure. NS, Normal saline.

To prevent recurrence, patients who have infected epidermoid (or sebaceous) cysts containing foul-smelling cheesy material should be referred for complete excision of the cyst after the infection and inflammation have resolved.

To prevent recurrence, patients who have infected epidermoid (or sebaceous) cysts containing foul-smelling cheesy material should be referred for complete excision of the cyst after the infection and inflammation have resolved.

Instruct the patient to use intermittent warm water soaks or compresses for a few days when there is no packing used or after the packing is removed. This will encourage further drainage when needed.

Instruct the patient to use intermittent warm water soaks or compresses for a few days when there is no packing used or after the packing is removed. This will encourage further drainage when needed.

With the new prevalence of CA-MRSA, it is now appropriate to obtain aerobic cultures and sensitivities on most pus-containing lesions.

With the new prevalence of CA-MRSA, it is now appropriate to obtain aerobic cultures and sensitivities on most pus-containing lesions.

Antimicrobials that cover CA-MRSA should now be prescribed for all wounds that require antibiotic coverage (i.e., when extensive cellulitis is present). Most abscesses in immune-competent individuals, if not associated with lymphangitis or extensive cellulitis, probably do not need antibiotics at all: incision and drainage is curative. This is as true of MRSA infections as it is of non-MRSA lesions.

Antimicrobials that cover CA-MRSA should now be prescribed for all wounds that require antibiotic coverage (i.e., when extensive cellulitis is present). Most abscesses in immune-competent individuals, if not associated with lymphangitis or extensive cellulitis, probably do not need antibiotics at all: incision and drainage is curative. This is as true of MRSA infections as it is of non-MRSA lesions.

Empirical treatment currently includes 10 days of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim DS), 1 to 2 tablets q12h, alone or in combination with rifampin, 300 mg q12h; doxycycline (Vibramycin), 100 mg q12h; clindamycin (Cleocin), 300 to 600 mg q6-8h; or minocycline (Minocin), 100 mg q12h. Linezolid (Zyvox), 600 mg q12h, is also recommended, but it is prohibitively expensive in most cases ($1000 to $1500 for 10 days). Resistance to these drugs may develop in the future.

Empirical treatment currently includes 10 days of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim DS), 1 to 2 tablets q12h, alone or in combination with rifampin, 300 mg q12h; doxycycline (Vibramycin), 100 mg q12h; clindamycin (Cleocin), 300 to 600 mg q6-8h; or minocycline (Minocin), 100 mg q12h. Linezolid (Zyvox), 600 mg q12h, is also recommended, but it is prohibitively expensive in most cases ($1000 to $1500 for 10 days). Resistance to these drugs may develop in the future.

Severe infections should be treated with vancomycin, 1 g q12h, or 10 mg/kg q6h IV.

Severe infections should be treated with vancomycin, 1 g q12h, or 10 mg/kg q6h IV.

Large abscesses (larger than 5 cm) are likely to require hospitalization and surgical drainage.

Large abscesses (larger than 5 cm) are likely to require hospitalization and surgical drainage.

Other individuals for whom hospitalization should be considered include the immunosuppressed patient, the toxic febrile patient, or the patient who has a large area of cellulitis, involvement of the central face, or severe pain.

Other individuals for whom hospitalization should be considered include the immunosuppressed patient, the toxic febrile patient, or the patient who has a large area of cellulitis, involvement of the central face, or severe pain.

Provide a dressing to collect continued drainage.

Provide a dressing to collect continued drainage.

Have outpatients reexamined within 48 hours.

Have outpatients reexamined within 48 hours.

When multiple family members are involved or the abscesses are recurrent, stress the importance of good personal hygiene, recommend use of hexachlorophene soap for bathing, and prescribe 6 weeks of topical 2% mupirocin (Bactroban) for the nares to eradicate colonization and the carrier state for the patient and any contacts with positive nasal cultures. Athletes should be encouraged not to share personal equipment or towels and to regularly clean their sports gear.

When multiple family members are involved or the abscesses are recurrent, stress the importance of good personal hygiene, recommend use of hexachlorophene soap for bathing, and prescribe 6 weeks of topical 2% mupirocin (Bactroban) for the nares to eradicate colonization and the carrier state for the patient and any contacts with positive nasal cultures. Athletes should be encouraged not to share personal equipment or towels and to regularly clean their sports gear.

What Not To Do:

Do not incise an abscess that is pulsatile or lies in close proximity to a major vessel, such as in the axilla, groin, or antecubital space, without first confirming its location and nature by needle aspiration or, preferably, ultrasonography.

Do not incise an abscess that is pulsatile or lies in close proximity to a major vessel, such as in the axilla, groin, or antecubital space, without first confirming its location and nature by needle aspiration or, preferably, ultrasonography.

Do not treat deep infections of the hands as simple cutaneous abscesses. When significant pain and swelling exist or there is pain on range of motion of a finger, seek surgical consultation.

Do not treat deep infections of the hands as simple cutaneous abscesses. When significant pain and swelling exist or there is pain on range of motion of a finger, seek surgical consultation.

Do not fully “pack” an abscess cavity with ribbon gauze. This may actually trap pus within the cavity, inhibit drainage, and enlarge the eventual scar. The goal is to insert the gauze across all the surfaces of the cavity and provide some degree of débridement when the gauze is removed.

Do not fully “pack” an abscess cavity with ribbon gauze. This may actually trap pus within the cavity, inhibit drainage, and enlarge the eventual scar. The goal is to insert the gauze across all the surfaces of the cavity and provide some degree of débridement when the gauze is removed.

Do not use rifampin alone because of the rapid selection of resistant organisms.

Do not use rifampin alone because of the rapid selection of resistant organisms.

Discussion

Either trauma or obstruction of glands in the skin can lead to cutaneous abscesses. In the past, incision and drainage were considered the definitive therapy for most of these lesions, and therefore routine cultures and antibiotics were generally not indicated. In the past few years, however, there has been an increasing incidence worldwide of CA-MRSA skin infections, and now the rules have changed.

Strains of CA-MRSA usually carry a gene encoding the Panton-Valentine leukocidin toxin, which causes necrosis. These strains of S. aureus are able to colonize the skin or nares and can produce spontaneous lesions.

There have been community outbreaks of CA-MRSA among prisoners and athletic teams. Direct transmission of the skin infection may occur through poor hygiene practices, close living quarters, and shared contaminated objects, such as athletic equipment, towels, and benches. Other risk factors include skin trauma from turf burns and shaving.

Currently, there are few research data to provide a scientifically proven regimen for managing these infections. I&D is still a basic tenet for managing an abscess. However, most experts suggest that cultures should always be obtained and CA-MRSA–specific antimicrobials be prescribed if antibiotics are needed. Early follow-up is also recommended. Over time, most of these recommendations most certainly will change.

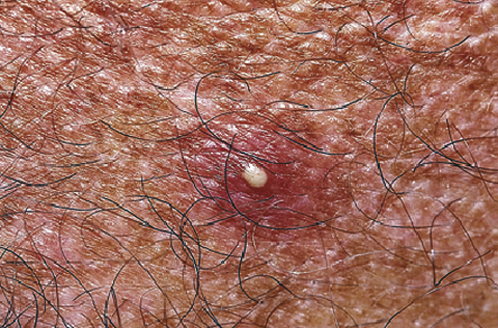

Folliculitis is a superficial infection of the hair follicle that results in mild pain or itching with a small red papule or pustule surrounding a hair shaft (Figure 163-4). Common sites for folliculitis usually include areas where short, coarse hair predominates, such as the beard, upper back, chest, buttocks, and forearms. Minor uncomplicated cases can be treated with warm compresses, gentle cleansing with antibacterial soap, and, if this alone is ineffective, 2% mupirocin ointment. Refractory folliculitis will require CA-MRSA–specific antimicrobials. Advising the patient to avoiding shaving these areas may be warranted.

Figure 163-4 Folliculitis. (From White G, Cox N: Diseases of the skin, ed 2. St Louis, 2006, Mosby.)

Hot tub folliculitis is caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. A patient usually presents within 72 hours after being in a hot tub with itchy red papules that will be most prominent on parts of the body covered by a bathing suit. Local treatment will usually suffice, but for severe cases, 7 to 10 days of ciprofloxacin (Cipro), 500 mg q12h, will usually clear up this rash.

A furuncle or boil is an extension of a folliculitis infection into the subcutaneous tissue. This forms a deep red, painful nodule that surrounds the hair shaft (Figure 163-5). Furunculosis is the most frequently reported presentation of CA-MRSA infections. The syndrome is characterized by the spontaneous development of primary necrotic lesions of the skin and soft tissues. These are the lesions that are often mistaken for spider bites by the patient. Crusted lesions and plaques progress to abscesses or cellulitis but may also present as impetigo, nodules, or pustules. Abscesses may become fluctuant and may drain spontaneously or require I&D and warm compresses. CA-MRSA–specific antimicrobials are now generally initiated.

Figure 163-5 Furuncle. (From White G, Cox N: Diseases of the skin, ed 2. St Louis, 2006, Mosby.)

A carbuncle results when individual furuncles coalesce, resulting in a large painful nodule with deep interconnected sinus tracts and multiseptate abscesses that often are draining pus from a cluster of pores (Figure 163-6). These are usually found on the back of the neck and generally require I&D with blunt dissection using a hemostat to break up the interconnected loculations of pus. Warm compresses and antibiotics are required as noted.

Figure 163-6 Carbuncle. (From White G, Cox N: Diseases of the skin, ed 2. St Louis, 2006, Mosby.)

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic inflammatory condition of the apocrine glands in the axilla and groin. Treatment for early lesions includes intralesional steroid injections, oral antibiotics, and isotretinoin (Accutane). Secondary infection typically results in abscess formation and fistulization requiring I&D and antibiotics. Local care with cleansers and compresses of Burow solution (Domeboro) is recommended, and patients should be encouraged to stop the use of antiperspirants. Recurrent I&Ds cause significant scarring, and extensive surgical procedures are eventually indicated.

A pilonidal cyst abscess is a relatively common finding in the sacrococcygeal region. Drainage should include a search for and removal of hair and follicular tissue at the base of the abscess cavity. Because Escherichia coli is a frequent infecting organism, these lesions may require broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage. To prevent recurrence after the initial infection has cleared, excision of the entire cyst cavity with marsupialization will eventually be required. Surgical referral is therefore necessary.

True brown recluse spider bites are actually very rare (see Chapter 161).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree