Chapter 12 Current Surgical Options for Intervertebral Disc Herniation in the Cervical and Lumbar Spine

Introduction

In 1990 nearly 15 million office visits to physicians occurred for mechanical low back pain, the fifth most common reason for seeking medical care.1 Axial spinal disorders and associated pain present an enormous economic burden on Western health care systems. In the United States from 2003 to 2007 the rate of complex fusion procedures increased 15-fold, and the odds ratio of life-threatening complications from complex fusion vs. simple decompression was 2.95.2 Little consensus exists regarding the choice of sole decompression vs. decompression combined with fusion.3,4 In addition, it appears that individual surgeon preference may impact surgical approach more than the surgical pathology.5 Success is highly varied, and long-term outcome studies are few. Great debate still surrounds disc surgery.

Cervical disc herniation is a common cause of pain that can frequently lead to disability. Cote, Cassidy, and Carroll6 reported that, among 2184 Canadian individuals randomly surveyed between the ages of 20 and 69 years of age, 54% noted significant neck pain in the prior 6 months, with 10% of those individuals rating their pain as “disabling.” In a 5-year series examining the natural history of cervical disc disease, 23% of patients remained partially or totally disabled with nonoperative care.7 Cervical symptoms can result from either direct compression of nerve roots by disc herniation or pain arising from the disc itself.

Cervical Disc Herniation Causing Neural Compression

Patient Selection

Neural compression from cervical intervertebral disc herniation often presents with severe neck pain with distal paresthesias with or without radiating interscapular pain.8 Ideal surgical patients present with radicular symptoms and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings that match the anticipated dermatomal level.9 The most commonly involved cervical disc herniations occur at the C5-C6 and C6-C7 levels, with the most common objective sensory deficits affecting C6 and C7 dermatomes and motor deficits most commonly affecting the biceps and triceps muscles.10 In addition, concordant neurological deficits such as motor weakness in the anticipated myotome, loss of associated motor reflex, and presence of Spurling’s sign give further support to disc herniation causing the patient’s symptoms and support consideration of surgical treatment. Ideal surgical candidates are those who have failed conservative treatment, including medication management, physical therapy, and epidural steroid injections. Patients with significant neurological symptoms, including worsening motor weakness, bowel or bladder dysfunction, or MRI findings showing significant cord compression, should be referred for surgical evaluation promptly. Younger patients more likely present with soft disc herniations level and are better surgical candidates than older patients with severe multilevel spondylosis.9

Surgical Approaches

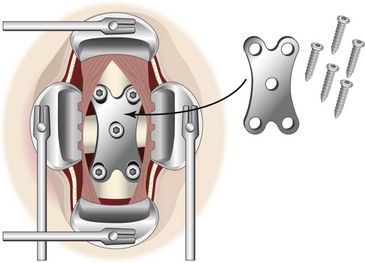

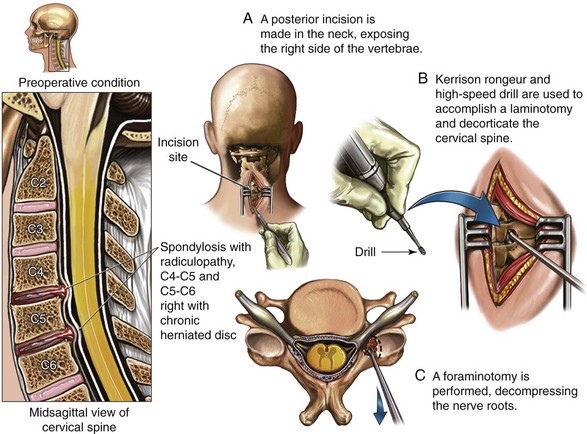

Surgical treatments for cervical disc herniation depend largely on the location of the disc herniation itself. They can be engaged from an anterior approach with hardware, posterior/posterolateral decompression, or posterior decompression with fusion. Patients with far-lateral disc herniations potentially can be candidates for posterolateral approaches such as keyhole foraminotomy and posterior laminotomy and discectomy. Keyhole foraminotomy describes a technique whereby lateral disc herniations are resected from the inferior aspect of the neural foramen while using a curette or similar instrument to retract the posterior-superior aspect of the foramen and visualize the neural and vascular elements (Fig. 12-1). To perform this technique, the lamina of the involved intervertebral level is resected with a rongeur and resected with either a Kerrison punch or high-speed drill. The lateral third of the ligamentum flavum is resected, the nerve is retracted superiorly, a microsurgical nerve hook is swept below the nerve root, and the disc is resected.9 The superior aspect of the neuroforamen is often visualized further by resecting part of the cervical facet joint. In a series of 172 patients with cervical lateral disc herniation, 97% of patients noted relief of radicular symptoms at a follow-up period of between 1 and 2 years. In this cohort of patients 35% underwent single-level cervical foraminotomy, 25% underwent single level laminotomy with discectomy, and 40% underwent two-level foraminotomy.9 Older patients often underwent two-level surgery (mean age 55) compared to younger patients who underwent single-level surgery (mean age 45).9 Other studies involving microsurgical foraminotomy revealed similar results.10–12 These studies also stressed the importance of selecting patients with soft lateral disc herniations, minimal myelopathy, and single-level disease.9–12 Central and paracentral disc herniations sometimes cannot be accessed with a posterior or lateral approach given the position of the spinal cord and the fact that the spinal cord cannot be retracted without severe neurological compromise. Generally younger patients presenting with soft disc herniations without significant spondylitic disease are better suited for posterior/posterolateral discectomy.

Fig. 12-1 Pictorial representation of cervical laminotomy and foraminotomy.

From Phototake Illustration/Stock Illustration Source.

A Cochrane database review of the literature in 2009 assessing the efficacy of posterior laminoforaminotomy for the treatment of cervical radiculopathy primarily due to soft lateral disc herniations or cervical spondylosis recommended posterior laminoforaminotomy as a surgical option with class III evidence.13 Older patients with severe spondylosis with broad-based central disc herniation with calcific stenosis can make posterior surgery more challenging.9 In addition, significant cervical spondylosis introduces additional pain generators, including cervical facet joints, cervical discogenic pain, uncovertebral joint pain, and cervical instability with Modic changes that may be better served by cervical fusion, which potentially addresses these additional pain generators. Multiple-level surgery increases the probability of instability since the posterior bony anatomy is weakened and may require the addition of posterior or anterior hardware to facilitate fusion, proper alignment, and stability.14

Potential advantages of posterior laminotomy/foraminotomy over anterior surgery/posterior fusion include maintaining segmental motion and proposed less common segmental disc degeneration in adjacent fused levels. The medical literature does not support one technique as being superior to the other either in the short or long term; the type of surgery performed is often a function of a surgeon’s particular training and comfort level.13

Anterior surgical approach is a suitable approach for cervical radiculopathy and for patients with a large central or paracentral disc herniation. Most of the studies looking at an anterior approach and outcomes have looked at patients with significant myelopathy, which is the result of a variety of pathologies, including cervical disc herniation, uncovertebral joint hypertrophy, facet joint arthropathy, and hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum, but who have generally shown neurological improvement in 80% to 90% of cases.15,16 Advantages of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) include arthrodesis of the spine that better corrects cervical kyphosis, better ability to target central disc herniations, better ability to treat ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL), and positive postoperative pain relief.16 Beginning in the 1950s there has been a shift from posterior to anterior surgery.17 Anterior cervical surgery was first pioneered by Cloward in 195818 and involves retracting the trachea and vascular structures to visualize the involved intervertebral level, decorticating the vertebral endplates, resecting the disc preserving the posterior longitudinal ligament, and placing an anterior plate for stability (Fig. 12-2). The Robinson-Smith is similar to the Cloward procedure except that the vertebral endplates are preserved.19 Comparisons for anterior and posterior surgical decompression for cervical disc herniation have yielded similar results.20 Anterior fusion can better address the site of pathology with a central disc herniation. Nerve root trauma associated with a posterior approach can also be reduced with ACDF. In addition, the incidence of postoperative excessive neck flexion resulting from posterior surgical decompression and compromise of the ligamentous attachments to the C7 spinous process can be avoided with an anterior approach. Few studies specifically comparing anterior and posterior approaches for cervical herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP) exist, although studies evaluating cervical spinal myelopathy for anterior and posterior approaches have yielded similar results.21,22

Surgical Complications

Infection after cervical surgery overall occurs between 0% and 18% of the time.23–28 Similar rates have been reported for anterior and posterior surgery, although some authors have reported lower rates for anterior surgery.25,27 Higher infection rates have been reported in patients with systemic illness, patients on long-term steroids, and immunocompromised patients.29 Other complications include nerve injury, pulmonary embolism, spinal cord injury, esophageal rupture, and death.23–25 With anterior surgery plate nonunion or dislocation can occur, and with posterior decompressive surgery kyphotic deformity can develop.14,30

Cervical Disc Replacement

Cervical disc replacement is intended for one- or two-level disc disease, although other applications are emerging as well. Artificial disc replacement involves a polyurethane nucleus surrounded by two titanium alloy shells that contain a porous coating to help promote cortical anchoring. In a study of 103 patients with symptomatic radiculopathy and myelopathy, 90% of patients noted greater than 50% improvement of preoperative signs and symptoms with single-level disc replacement.31 Data for 1 and 3 years have shown success for patients with one- and two-level disc disease, although longer-term studies evaluating device-related complications are needed.31,32 This study did not show any significant device migration, although several incidences of anterolateral paravertebral ossification were noted on computed tomography (CT) scan. Longer-term data are needed to demonstrate long-term efficacy and the absence of complications, including device migration. A more recent application of placement of cervical arthroplasty after prior fusion and adjacent-level disc degeneration has also been reported that may be more beneficial than extending fusion levels for treating patients with adjacent-level stenosis.33

Lumbar Disc Herniation and Surgical Approaches

Lumbar disc herniation commonly causes not only low back pain but also radicular pain. It is more common among males, and 70% of those affected are between ages 20 and 40 years; the gross majority of herniations occur at L4-L5 and/or L5-S1.34 Surgery is indicated when conservative pain treatment measures have failed or there is significant risk of, or impending, neurological injury. This section discusses the various approaches, considerations for surgical planning and technique, and the reported outcomes for anterior decompression (discectomy) and fusion (anterior lumbar interbody fusion [ALIF]), extreme lateral interbody fusion (XLIF), transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF), posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF), and disc replacement.

Lumbar Discectomy

Oppenheim and Fedor Krause initially developed discectomy in 1906.35 To obtain access to the anterior epidural space, fenestration, laminectomy, and hemilaminectomy were developed and are still mainstream approaches to exposure to the large free-fragment disc pathology contributing to neural pressure. Today unilateral transflaval microdiscectomy is standard of care for treatment of patients with symptomatic disc herniation.36 Historically percutaneous approaches, including chymopapain injection, automated percutaneous discectomy, and multiple other approaches were indicated as a whole for contained disc herniation. Nevertheless, the appeal of small incision and minimally invasive approaches led Casper,37 Williams,38 and Yasargil39 to use microscopes to achieve less muscle and epidural scarring, resulting in diminished perioperative morbidity and higher satisfaction. In 1997 Foley and Smith pioneered the muscle-splitting technique of tubular discectomy, common with such surgical systems as the METRx (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minn).36 The gross majority of lumbar discectomies are performed by either open, microscope-assisted microdiscectomy or tubular approaches using either an endoscope or microscope.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree