Figure 26.1

Normal anorectal anatomy

Figure 26.2

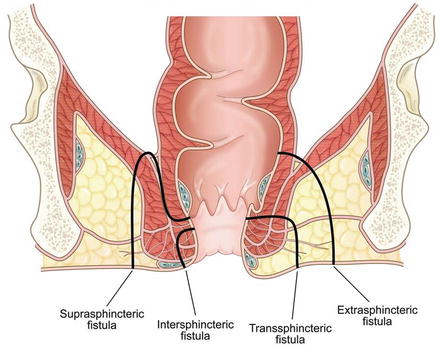

Location of anorectal abscesses

Perioperative Care

Preoperative Preparation

Preoperative imaging is not routinely recommended. CT, MRI, or endoanal ultrasound studies may be used to clarify the anatomic location of complex, recurrent, or atypical presentations, or to differentiate isolated Crohn’s-associated rectal inflammation from true abscess or fistula, but may be deferred in typical cases. Examination under anesthesia is usually the most efficient means to both confirm a questionable diagnosis and provide definitive treatment. Pre-procedure antibiotics are indicated for prosthetic valves, history of infective endocarditis, some forms of congenital heart disease, and heart transplant recipients with valve disease [5].

Positioning and Anesthesia

The choice of positioning and anesthesia depends on the location and extent of the abscess. Perianal abscesses are often palpable at the anal verge, and may be effectively drained at the bedside in the lateral decubitus position under local anesthesia. However, ischioanal, intersphincteric, and supralevator abscesses can be large and require examination under anesthesia to confirm location and extent. Therefore, these abscesses should be drained in the operating room in either lithotomy or prone jackknife position. Regional, local with monitored anesthesia care, or general endotracheal anesthesia may be utilized as long as the patient is sufficiently relaxed to facilitate anoscopy and complete examination. The legs must be adequately padded while in lithotomy stirrups, and sequential compression devices should be used.

Description of Procedure

Anorectal Abscess Drainage

Candidates for bedside drainage include patients without (1) signs/symptoms of sepsis, including hypotension, high fever, and leukocytosis, (2) evidence of fistula or fissure on physical exam, (3) history of IBD, (4) history of prior complex cryptoglandular disease, (5) history of recent abscess drainage or fistula procedure, (6) history of recent abdominal or pelvic operation, or (7) CT evidence of complex disease, including supralevator, intersphincteric, or horseshoe type configuration. All patients should be initially examined in the lateral decubitus position for an area of fluctuance in the perianal skin, generally with overlying erythema and occasional drainage. Once identified, those patients who are candidates for bedside drainage should have the area cleansed with chlorhexidine scrub. Lidocaine with epinephrine is infiltrated to provide local anesthesia to the overlying skin and surrounding tissue, and IV or PO narcotics may be administered for pain relief. An 18-gauge needle may be used to determine the location of the underlying purulent fluid. A generous cruciate incision is then made over the area of fluctuance using an 11-blade scalpel, and the corners of skin are removed. Removing the corners of skin prevents early closure of the cavity and recollection of the abscess. Alternatively, an elliptical incision may be utilized. Care should be taken to make the incision close to the sphincter muscles in order to minimize the formation of complex fistulas with long tracts. Drainage of the cavity is facilitated by digital manipulation or lysis of intraluminal loculations with a Kelly clamp as needed. The cavity is then copiously irrigated with normal saline and explored to ensure no further areas of fluctuance requiring drainage. Sterile packing tape is used to lightly pack the cavity, which is then covered using sterile gauze.

Patients with any of the features concerning for complex abscess listed above should be brought to the operating room for examination under anesthesia and abscess drainage. Following induction of anesthesia, the patient is placed in either high lithotomy or prone jackknife position based on surgeon preference. The perineum is prepped and draped in sterile fashion. Digital rectal examination is performed to evaluate for palpable mass, fissure, fistula opening, or other abnormality. An anoscope is then inserted, and visual examination for fissure or fistula is carefully performed. The location of the abscess cavity is determined relative to the sphincter complex and the pelvic floor muscles.

Perianal abscess: identified by bulging of perianal skin. A cruciate or elliptical incision should be made over the area of maximal fluctuance and the abscess cavity drained and irrigated as described above.

Ischioanal abscess: identified by bulging over the ilioanal fossa. The incision should be made as medially as possible, close to the sphincter complex, to reduce the risk of large/complex transsphincteric fistula formation. A horseshoe abscess is identified by bulging in the posterior and lateral anal canal and is drained via a longitudinal incision between the coccyx and the anal canal. This exposes the anococcygeal ligament, which is then incised along its fibers to facilitate entry into the deep postanal space and subsequent abscess drainage. Counter-incisions may be required over the ischioanal spaces on either side of the rectum. As described above, these incisions should be made lateral and as close to the sphincter complexes as possible.

Intersphincteric abscess: identified by bulging in the posterior (most commonly) or lateral anal canal within the sphincter complex but with minimal or absent external exam findings. An incision is made through the anal mucosa dividing the internal sphincter and may require widening to facilitate complete drainage, while preserving as much sphincter mass as possible. A mushroom tip catheter is left in the cavity and secured with suture to prevent the sphincter muscles from contracting and thereby preventing adequate drainage [6].

Supralevator abscess: identified by palpation of a tender mass on posterior or lateral rectum above the anorectal ring. Drainage route is determined by associated pathology:

If associated with ischioanal abscess, drain through cruciate incision on the perianal skin near the sphincter complex to avoid formation of extrasphincteric fistula.

If associated with intersphincteric abscess, drain through rectum to avoid formation of complex suprasphincteric fistula.

If associated with intraabdominal abscess, use imaging to guide choice of incision.

Additional Operative Considerations

Large cavities may require placement of a small mushroom tip catheter to serve as a drain and maintain patency of the external tract. The external component of this drain should be kept relatively short (2–3 cm) and sutured in place to prevent dislodgement. Postoperatively, the patient should be taught how to flush the drain with sterile saline and perform a gentle irrigation twice daily. The drain can be downsized once per week as tolerated until the cavity is small and manageable with local wound care.

There has been debate in the literature regarding whether or not to perform a fistulotomy at the time of initial incision and drainage of anorectal abscess. The main reason cited for deferring primary fistulotomy is that it exposes patients to the risk of sphincter compromise when they may not have gone on to develop a persistent fistula-in-ano. However, the proposed advantage is reduced recurrence of abscess and avoidance of a second operation for fistulotomy. A 2010 Cochrane review addressed this question, and meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials including 479 patients concluded that in the setting of perianal abscess associated with low anal fistula, primary fistulotomy significantly reduces the risk of persistent abscess, fistula, and need for repeat surgery, without significantly compromising continence [7]. Regardless, the decision to perform primary fistulotomy should be made on an individualized basis.

Special Postoperative Considerations

All patients should begin sitz baths two times per day on postoperative day number two. Such a regimen ensures perianal hygiene and improves comfort of the area. Fiber or other bulk-producing agents should be added to a regular diet to prevent diarrhea and improve hygiene. There is no role for postoperative antibiotic therapy in most cases. Antibiotics may be considered in patients with significant associated cellulitis, systemic sepsis, valvular heart disease, mechanical valve, diabetes, or immunosuppression [3, 4]. Close follow-up is necessary as there is approximately 30% risk of recurrent anorectal sepsis and 30–50% risk of fistula formation requiring future intervention [4, 6].

Fistula-in-Ano

Indications

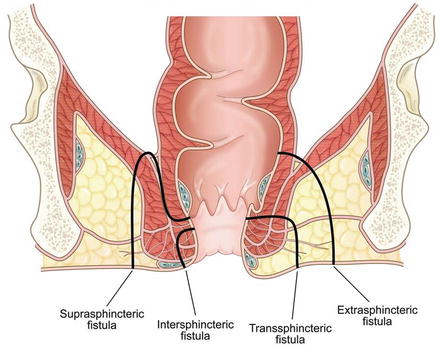

In approximately one-third to half of patients who experience a cryptoglandular abscess, an inflammatory tract develops and persists between an internal opening at the dentate line and an external opening on the perianal skin, defined as a fistula-in-ano [1, 2, 4]. The location and course of the fistula directly reflects the location of the original abscess and is classified anatomically in relation to the sphincter muscles: (1) intersphincteric (2) transsphincteric (3) suprasphincteric (4) extrasphincteric [8] (Fig. 26.3). Patients present with persistent purulent drainage from the internal and/or external openings, either spontaneously or following I&D procedures for abscess. Differential diagnosis considerations include pilonidal sinus, hidradenitis suppurativa, infected perianal cysts, diverticular disease, IBD, malignancy, or radiation injury. In general, the location of a fistula tract and its internal opening follows Goodsall’s rule. This rule suggests that when the external opening is located within 3 cm of the anal verge and is anterior to a transverse line through the anus, then the tract travels radially in a straight line to the anal canal. Alternatively, when the external opening is located within 3 cm of the anus and posteriorly, the tract follows a curvilinear path terminating in the posterior midline of the anal canal.

Figure 26.3

Location of fistula-in-ano

Perioperative Care

Preoperative Preparation

Although most fistulae-in-ano represent sequelae of spontaneous or surgical drainage of anorectal abscess, risk factors for underlying malignancy and inflammatory bowel disease must prompt consideration of a colonoscopy prior to operation. As a general rule, fistulizing Crohn’s disease should be managed with aggressive medical rather than surgical therapy [1]. Techniques for identifying tract location include digital palpation or imaging techniques such as endoanal ultrasound and MRI, with or without injection of dilute hydrogen peroxide. In one cohort, these methods successfully identified 61, 81, and 90% of fistulous tracts, respectively [9]. If local inflammation is minimal, enemas should be given the night before the procedure; complete bowel preparation is not necessary. Preoperative antibiotics should be given prior to incision.

Positioning and Anesthesia

The patient is placed in either lithotomy or prone jackknife position based on surgeon preference. Regional, local with monitored anesthesia care, or general endotracheal anesthesia may be utilized, but must adequately relax the patient to facilitate anoscopy. Care should be taken to ensure adequate padding of the legs and other pressure points, and sequential compression devices should be placed on all patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree