Craniofacial Injury

Christopher R. Forrest MD, MSc, FRCSC, FACS

ANATOMIC AND PHYSIOLOGIC CONSIDERATIONS IN CHILDREN

Cranial to facial ratio.

3 months: Cranium to face = 8:1.

2 years: Cranium to face = 4:1.

5.5 years: Cranium to face = 2.5:1.

Adult: Cranium to face = 2:1.

Cranial-orbital injuries more common in children under age 5 years due to relative prominence of forehead (Fig. 7-1).

Presence of paranasal sinuses.

Act as “air-bags” for the vital structures and influence fracture patterns.

Fronto-orbital injuries more commonly associated with anterior cranial fossa fractures when frontal sinus absent or underdeveloped.

Radiographic evidence of paranasal sinuses:

Maxillary: 4 to 5 months.

Ethmoids: 12 months.

Frontal: 6 years.

Bone morphology.

Greater cancellous to cortical ratio.

More elastic and resistant.

Higher impact force per unit area needed for fracture.

Higher incidence of associated injuries.

Tooth buds and dentition.

Unerupted tooth buds increase strength and compliance of facial skeleton.

Three groups:

0 to 5 years: Primary dentition.

6 to 11 years: Mixed dentition.

12 to 16 years: Permanent dentition (Fig. 7-2).

Bone metabolism.

Increased metabolism in children.

Faster healing (3 weeks).

Less time required for immobilization.

Active growth.

Potential for late growth disturbances after a fracture (both under and overgrowth).

Cranial vault.

Birth: 60% adult size.

2 years: 80% adult size.

6 years: 90% adult size.

Nose.

Maximum growth 10 to 14 years.

Growth complete by 16 years.

Orbits.

90% adult size by age 7 years.

Maxilla and palate.

6 years: 65% adult size.

10-12 years: Nearly complete.

Mandible.

Last bone to grow.

Indicator of skeletal maturity.

Female: 14 to 16 years.

Male: 18 to 21 years.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Severe facial fractures in children are relatively uncommon.

1.3% to 4.9% of all facial fractures occurred in <11 years old.

4% to 9.2% of all facial fractures occurred in <16 years old.

Incidence of injuries increases after age 5 years.

<5 years: <5% (high level of supervision).

>5 years: 95% due to rapid neuromotor development.

Male:female 2 to 3:1.

Causes (age dependent):

Falls > MVA > pedestrians > bicycles > sports.

Distribution: >7 years—the pointy bits: Nose and mandible more common.

Associated injuries: Present in up to 73-88% of cases of facial fractures.

Common:

Closed head injury.

Skull.

Ocular and soft tissue.

Uncommon:

C-spine.

Thoracic.

Abdominal.

HISTORY

History of injury.

Awareness of possible nonaccidental injury.

Premorbid history of orthodontics important to help establish occlusion.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

See specific regions.

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

Key to confirm or establish diagnosis of facial fractures as children may be difficult to examine and uncooperative.

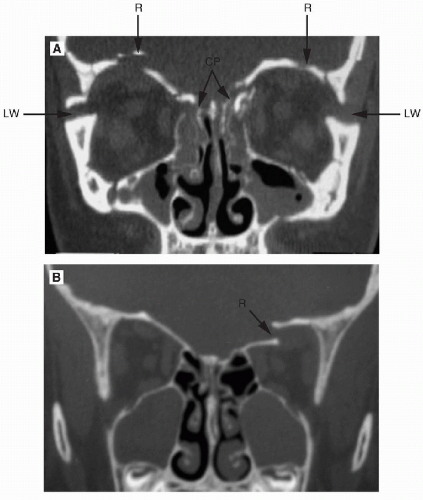

CT scan (axial, coronal, and 3-D) first line of radiologic investigation.

Oblique sagittal views useful to visualize orbital floor.

Plain x-rays notoriously unreliable in establishing the diagnosis.

Panorex—ideal in diagnosis of mandibular fractures.

Occlusal views occasionally useful in dental-alveolar fractures.

EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT

ABCs of trauma (See Chapter 2 on Primary Surgery for details).

Nasal packs (anterior plus/minus posterior) important to control midface bleeding.

Soft tissue injuries may give clues to presence of fractures.

SPECIFIC INJURIES

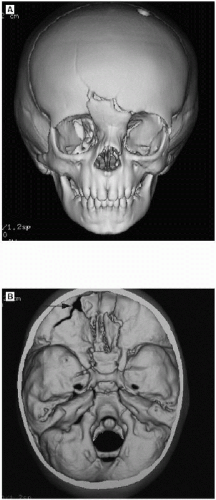

Cranial-Frontal Region (Fig. 7-3)

More frequent in children <5 years of age due to prominence of forehead.

Lack of frontal sinus until teen years predisposes to orbital roof fractures and frontal lobe injuries.

CSF leak possible (through cribriform or orbital roof).

Optic nerve at risk for injury with frontal trauma even in the absence of fractures.

History

High-velocity trauma.

Look for evidence of brain injury.

Possibility of ocular trauma.

Physical Examination

Forehead laceration could indicate compound skull fracture.

Periorbital swelling and ecchymosis.

Frontal contour depression.

Pupil reaction—rule out relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) suggesting optic nerve injury.

Change in globe position inferiorly may occur due to orbital roof fragment pushing eye downwards.

CSF rhinorrhea.

Investigations

CT scan: Brain and facial bones windows.

Intracranial air (pneumocephalus).

Orbital roof.

Medial orbital wall.

Frontal bone.

Cribriform plate and anterior cranial base.

Opacification of ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses.

Management

Consultations.

Neurosurgery: Rule out brain injury/CSF leak.

Ophthalmology: Establish visual integrity.

Plastic surgery:

Definitive management when patient stable.

Repair lacerations.

Open reduction and internal fixation displaced fractures involving frontal bone, orbital roof, nasal-orbital-ethmoid regions when patient is stable or at same time as any neurosurgical intervention.

Complications

CSF leak (meningitis, intracranial abscess).

Facial deformity (depression, ocular dystopia).

Frontal sinus mucocele (in children >12 years).

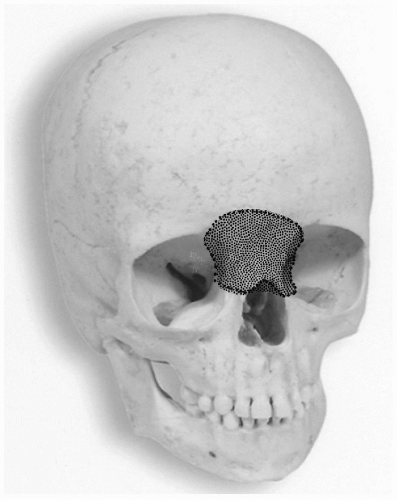

Naso-Orbital Ethmoid Fractures (Fig. 7-6)

Fracture complex involving the region of the medial orbits, nasal bones, and midline frontal areas.

May be unilateral or bilateral.

Classified radiologically by size of bone fragment attached to medial canthal ligament.

Characterized by:

Flattened and widened nasal dorsum.

Acute nasofrontal angle.

Telecanthus—increased distance of medial canthus from midline.

Enophthalmos (unilateral or bilateral).

History

High-velocity trauma.

Look for evidence of ocular injury.

Sensory disturbance V1 and supratrochlear nerves.

Diplopia due to medial wall fracture.

Epiphora.

Epistaxis.

Physical Examination

Swelling frontal nasal region.

Tenderness along inferior orbital rims and nasal bones.

Periorbital ecchymosis.

Telecanthus.

Enophthalmos.

Medial rectus entrapment with diplopia.

Flattened nasal dorsum.

Widening of nasal base.

Acute nasofrontal angle (with impaction of nasal bones).

FIGURE 7-5 • 3-D CT images showing disruption of orbital roof and anterior cranial base and left orbital roof in a 3-year-old boy. |

FIGURE 7-6 • Nasoorbital-ethmoid region.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|