Constipation

Prevalence

Constipation is the infrequent and difficult passage of small hard faeces. About 80% of patients in palliative care will require laxatives.

- Infrequent hard stools

| Associated symptoms | Symptoms of complications |

|

|

Assessment

History

The frequency and consistency of stools, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, distension and discomfort, mobility, diet, and previous bowel habit should be determined. In patients with a history of diarrhoea, true diarrhoea should be distinguished from overflow due to faecal impaction.

Examination

Constipation must be distinguished from obstruction due to tumour. Faecal masses are indentable, mobile, and rarely tender and may be palpable in the colon. In contrast, tumour masses are usually hard, fixed, and often tender. In obstruction, auscultation of the abdomen may reveal high pitched tinkling bowel sounds.

Digital examination may show an empty rectum or stoma in constipation—hard stools can lie higher in the bowel. However, 90% of impactions occur in the rectum, so examination can distinguish overflow from true diarrhoea.

Investigation with radiography

If the diagnosis of constipation is still unclear, despite an accurate history and examination, supine and erect abdominal radiography will show the characteristic meniscal appearance of gas and fluid filled bowel.

Management of constipation

The most important causes of constipation are immobility, poor fluid and dietary intake, and drugs, particularly opioids. Good general symptom control will minimise the first three of these, but most patients will require laxatives. The aim of laxative therapy is to achieve comfortable defecation, rather than any particular frequency of bowel movement. The choice of laxative depends on the nature of the stools, acceptability to the patient, and cost. Dose should be titrated against individual response. Clinically it is useful to divide laxatives into two groups:

- Predominantly softening

- Predominantly stimulating peristalsis

Radiograph of constipated patient showing masses and trapped gas

| Causes of constipation | |

| Caused by cancer | Associated with debility |

|

|

| Caused by treatment | Concurrent disorders |

|

|

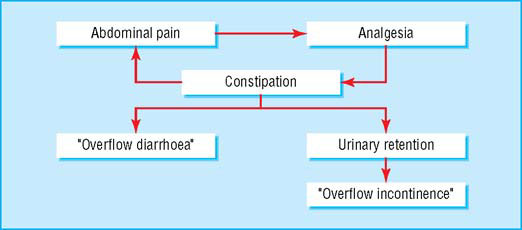

Vicious cycle of constipation associated with opioid analgesics

Systematic reviews suggest most laxatives have similar effectiveness, but in constipation related to opioid use, doses and adverse effects can both be minimised by the use of a combination of softening and stimulant laxatives.

Predominantly softening laxatives

Surfactant laxatives, such as poloxamer and docusate, act as detergents, increasing water penetration and hence softening the stools. They are available in combination with the peristalsis stimulator dantron.

Osmotic laxatives—Lactulose is popular but can cause bloating and flatulence and is too sweet for some patients. Saline laxatives, such as magnesium sulphate or hydroxide, have a mixed osmotic and stimulant mode of action and at higher doses can be strongly purgative. Magnesium hydroxide in combination with the lubricant softener liquid paraffin (now rarely used on its own) is a cheaper alternative to lactulose. Macrogols (polyethylene glycols) are administered with fluid, and they do not therefore draw further fluid from the body into the bowel. These drugs are now commonly used.

Non-absorbable fluid is provided by polyethylene glycol. The volume required can be difficult for ill patients.

Bulk forming agents are stool normalisers rather than true laxatives. They are less helpful in patients with cancer because of the volume of water required, their unproved efficacy in severe constipation, and the possibility of worsening an incipient obstruction.

Stimulant laxatives

These drugs stimulate the myenteric plexus to induce peristalsis and reduce net absorption of water and electrolytes in the colon. The latency of action is 6–12 hours. They can cause abdominal colic and severe purgation. Giving a stimulant in combination with a softening laxative may reduce colic. The most popular stimulants are senna and dantron. Patients given dantron may experience reddish discoloration of the urine and perianal rash, particularly in incontinent patients. (Dantron preparations are reserved for patients who have advanced cancer.)

Rectal laxatives

Suppositories or enemas are sometimes necessary but should never accompany an inadequate prescription of an oral laxative. They are appropriate for treating faecal impaction and for conditions such as spinal cord compression, when long term use may be necessary.

Diarrhoea

Diarrhoea is much less common than constipation in patients with advanced disease, affecting less than 10% of patients with cancer admitted to hospital or palliative care units.

Causes

The most common cause of diarrhoea in patients with advanced disease is use of laxatives. Patients may use laxatives erratically; some wait until they become constipated and then use high doses of laxatives, with resultant rebound diarrhoea. Among elderly patients admitted to hospital with non-malignant disease, constipation with faecal impaction and overflow accounts for over half the cases of diarrhoea.

Management

The underlying cause should be investigated, but relief is generally achieved with non-specific antidiarrhoeal agents—loperamide (up to 16 mg daily) or codeine (10–60 mg every four hours). Codeine may cause central effects, but these are rare with loperamide.

- Is the rectum or stoma full?

- Is the stool hard or soft?

- Is the rectum or stoma empty but the colon full?

- Are the rectum and colon both full?

- Does the patient have rectal sensation?

- Does the patient have normal anal tone?

- If a cord lesion is present what is the level?

- Bisacodyl suppository—Evacuates stools from rectum or stoma; for colonic inertia

- Glycerine suppository—Softens stools in rectum or stoma

- Phosphate enema—Evacuates stools from lower bowel

- Arachis oil enema—Softens hard impacted stools

Access and ability to get to a toilet may be more important in patients with constipation than supply of laxatives

| Causes of diarrhoea in patients with advanced disease | |

|

|

Rarely, patients with intractable diarrhoea may require a subcutaneous infusion of octreotide; the usual indication is a high effluent volume from a stoma. Diarrhoea due to malabsorption, often associated with pancreatic cancer, responds to pancreatic enzyme supplementation.

Intestinal obstruction

Epidemiology and pathophysiology

Intestinal obstruction is any process preventing the movement of bowel contents, thus leading to the partial or complete blocking of faeces and gas through the intestinal passage. Malignant intestinal obstruction (MIO) is common in patients with abdominal or pelvic cancers, with the highest incidence ranging from 5.5% to 51% in women with ovarian carcinoma, in whom it is a major cause of mortality. MIO occurs in 4.4% to 28.4% in patients with colorectal cancer and has been reported in patients with other advanced cancers, ranging from 3% to 15% of cases. Intestinal obstruction can be partial or complete, single or multiple, and due to benign causes (ranging from 6.1% in ovarian and other gynaecological cancers to 48% in colorectal cancer) or malignant causes. The small bowel is more commonly affected than the large bowel (61% υ 33%) and both are affected in over a fifth of patients.

Several mechanisms may be involved in the onset of MIO, and there is variability in both presentation and aetiology. At least three factors occur in bowel obstruction:

- Accumulation of gastric, pancreatic, and biliary secretions that are a potent stimulus for further intestinal secretions

- Decreased absorption of water and sodium from the intestinal lumen

- Increased secretion of water and sodium into the lumen as distension increases.

Loss of fluids and electrolytes results in breakdown of the sequence of secretion and reabsorption in the gastrointestinal tract. Secretions accumulate in the bowel above the obstruction. The volume of secretions tends to increase after intestinal distension and the consequent increase in the surface area, thus producing a vicious circle of secretion-distension-secretion.

The vicious circle represented by distension-secretion-motor hyperactivity exacerbates the clinical picture, producing intraluminal hypertension and epithelial damage. Epithelial damage generates an inflammatory response and the release of prostaglandins, potent secretagogues, either by a direct effect on enterocytes or enteric nervous reflex. Furthermore, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) might be released into the portal and peripheral circulation. This mediates local intestinal and systemic pathophysiological changes accompanying small intestinal obstruction, such as hyperaemia and oedema of the intestinal wall and accumulation of fluid in the lumen due to its stimulating effects.

Signs, symptoms, diagnosis, and investigations

In patients with cancer, compression of the bowel lumen develops slowly and often remains partial. As a consequence of the partial or complete occlusion to the lumen and/or dysmotility, the accumulation of the unabsorbed secretions produces nausea, vomiting, intermittent or complete constipation, pain, and colicky activity to surmount the obstacle that causes colicky pain. Abdominal distension may be absent in high obstruction—that is, of the duodenum or proximal jejunum—and when the bowel is “plastered” down by extensive mesenteric spread.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree