CONSTIPATION

ROSE C. GRAHAM, MD, MSCE

Constipation is an important problem in the pediatric emergency department for many reasons. It is one of the most common pediatric complaints, accounting for 3% of primary care visits. There are many causes for constipation (Table 13.1), some rare and some very common (Table 13.2). Most constipation in children is functional, meaning that no underlying medical disease is responsible. Occasionally, the presentation of constipation is atypical, with chief complaints that superficially seem unrelated to the gastrointestinal tract (Table 13.3). Although relatively rare, some causes of constipation are potentially life-threatening and need to be recognized promptly by the emergency physician (Table 13.4). In addition, constipation may produce symptoms that mimic other serious illnesses such as appendicitis.

DEFINITION

Although constipation most commonly is defined as decreased stool frequency, there is not one simple definition. The stooling pattern of children changes based on age, diet, and other factors. Average stooling frequency in healthy infants is approximately four stools per day during the first week of life, decreasing to 1.7 stools per day by 2 years of age, and approaching the adult frequency of 1.2 stools per day by 4 years of age. Nevertheless, normal infants can range from seven stools per day to one stool per week. Older children can defecate every 2 to 3 days and be normal.

It is easier to define constipation as a problem with defecation. This may encompass infrequent stooling, passage of large and/or hard stools associated with pain, incomplete evacuation of rectal contents, involuntary soiling (encopresis), or inability to pass stool at all.

PHYSIOLOGY

The passage of food from mouth to anus is a complex process that relies on input from intrinsic nerves, extrinsic nerves, and hormones. The colon is specialized to transport fecal material and balance water and electrolytes contained in the feces. When all is functioning well, the fecal bolus arrives in the rectum formed but soft enough for easy passage through the anus. Normal defecation requires the coordination of the autonomic and somatic nervous systems and normal anatomy of the anorectal region. The internal anal sphincter is a smooth muscle, innervated by the autonomic nervous system and tonically contracted at baseline. It relaxes involuntarily in response to the arrival of a fecal bolus in the rectum, allowing stool to descend to the portion of the anus innervated by somatic nerves. At this point, the external anal sphincter, striated muscle under voluntary control, tightens until the appropriate time for fecal passage. Before defecation, squatting or sitting straightens the angle between the rectum and anal canal, allowing easier passage. Voluntary relaxation of the external anal sphincter and increasing intra-abdominal pressure via Valsalva allow passage of the feces.

EVALUATION AND DECISION

The evaluation of the child presumed to have constipation should begin with a thorough history and physical examination. Special attention should be paid to the age of the patient, duration of symptoms, timing of first meconium passage after birth, changes in frequency and consistency of stool, stool incontinence, pain with defecation, rectal bleeding, presence of abdominal distention and/or palpable feces, and a rectal examination to assess anal position, sphincter tone, widening of the rectal vault, and presence of hard stool. Signs and symptoms that raise concern for more serious underlying diagnoses include onset of constipation in the first month of life, delayed meconium passage >48 hours, ribbon-like stools, blood in stool without anal fissure, failure to thrive, bilious emesis, fever, severe abdominal distention, abnormally positioned/appearing anus, or abnormal neurologic examination.

A complaint of constipation is not sufficient for diagnosis. A decrease in stool frequency or the appearance of straining is often interpreted as constipation. The physician should be aware of the grunting baby syndrome, or infant dyschezia, in which an infant grunts, turns red, strains, and may cry while passing a soft stool. This is the result of poor coordination between Valsalva and relaxation of the voluntary sphincter muscles. Examination reveals the absence of palpable stool in the rectum or abdomen. Complaints of constipation not supported by history or physical examination are called pseudoconstipation (Fig. 13.1).

Acute Constipation

Constipation is not a disease; it is a symptom of a problem. Constipation is acute when it has occurred for less than 1 month’s duration. The patient’s age and the duration of the constipation are important when determining the cause and significance of the problem.

The infant younger than 6 months of age with acute constipation is particularly concerning. Potential causes include dehydration, malnutrition, infant botulism, and anorectal malformations. A recent viral illness accompanied by dehydration from vomiting, diarrhea, fever, and increased respiratory rate can precipitate acute constipation in an infant. Adynamic ileus or decreased intake after gastroenteritis may slow transit through the colon, leading to hard stools. Dietary protein allergy (i.e., cow’s milk protein allergy) may present with constipation. Anal fissures and/or diaper rash after a bout of diarrhea may precipitate painful defecation, resulting in stool retention.

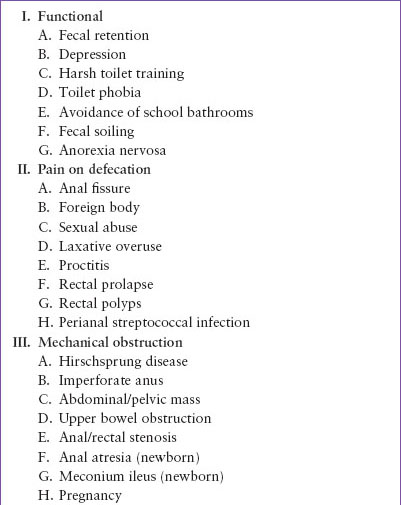

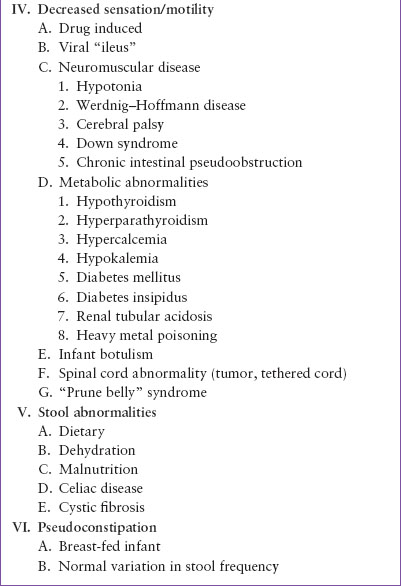

TABLE 13.1

ETIOLOGY OF CONSTIPATION

TABLE 13.2

COMMON CAUSES OF CONSTIPATION

Inadequate fluid intake and malnutrition should be uncovered by dietary history. Recent medications may cause constipation (Table 13.5). Ingestion of lead is also a potential and serious reason for constipation. Infant botulism presents with acute constipation, weak cry, poor feeding, and decreasing muscle tone (see Chapter 105 Neurologic Emergencies). Acute constipation can also be a symptom of a bowel obstruction, but usually a less prominent feature than other symptoms (see Chapter 124 Abdominal Emergencies).

Acute constipation in the child ≥6 months of age occurs for many of the same reasons as in the young infant. History may reveal dietary factors such as introduction of solid foods or excessive intake of cow’s milk, recent viral illness or use of medication, as well as the presence of underlying illness, such as neuromuscular disease. Physical examination will rule out anal malformations and other physical problems that could result in trouble defecating.

Chronic Constipation

Constipation of more than 1 month’s duration in a young infant <6 months of age, although likely to be a functional problem, is especially concerning and should prompt consideration of an underlying illness. Spinal muscular atrophy, amyotonia, congenital absence of abdominal muscles, dystonic states, and spinal dysraphism, cause problems with defecation and can be readily diagnosed with history and physical examination.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree