Congenital and Acquired Vision Disorders

Morton A. Alterman MD

INTRODUCTION

Education programs in primary care usually allow little time for exposure to ocular disease, despite vision being considered the dearest of senses. The effort to evaluate the eyes systematically as part of each examination is important. The eyes are exposed organs, and a great deal may be learned from their examination without needing the specialized equipment found in the eye clinic. The ophthalmoscope may be helpful for external and internal examination. If additional instruction in its use is necessary, the provider may find a short time with a friendly ophthalmologist or optometrist beneficial. This chapter provides content related to the assessment of visual acuity, as well as the diagnosis and primary care management of visual disorders commonly seen in pediatrics. Information related to rare eye diseases and serious complications of disease is presented briefly, because serious disease falls within the purview of the ophthalmologist.

VISUAL ACUITY

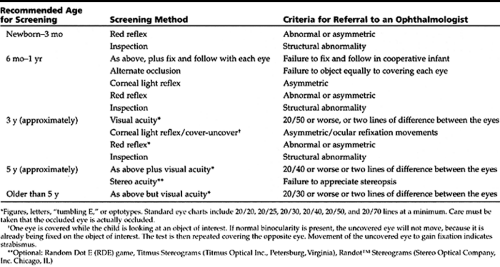

Testing of visual acuity or screening for potential vision problems can and should begin shortly after birth, when the red reflex may be evaluated and obvious structural abnormalities noted (American Academy of Ophthalmology [AAO], 1997). Table 52-1 guides the provider in the timing of screening examinations. It also provides criteria for ophthalmology referral.

Strabismus

The term “strabismus” is from a Greek root alluding to ocular misalignment. This cosmetic blemish may disturb a parent’s early attitudes toward a child and the child’s later relations with peers. Amblyopia is defined as diminished vision despite an anatomically normal eye. It is a frequent but usually reversible sequella of ocular misalignment if treatment starts in infancy or early childhood. Providers should encourage parents to seek early treatment and to continue regular follow-up. Amblyopia is unlikely to recur after age 9 or 10 years.

Epidemiology

Esotropia is a convergence of the ocular axes. It may be hereditary and is the most common form of strabismus. It occurs in 1% to 2% of births (Nelson, 1998). Infantile esotropia is categorized as being evident within the first 6 months of life. The degree of esotropia is usually quite marked. The infant may use the right eye to visualize objects to the left and the left eye to visualize objects to the right (crossed fixation). Esotropia may simulate bilateral sixth cranial nerve palsy, a much rarer cause of esotropia.

Acquired esotropia is most frequent between ages 1 and 3 years and commonly is related to hyperopia (farsightedness). Acquired esotropia has a marked propensity to cause amblyopia.

A complaint of double vision or a tendency to close one eye to avoid double vision indicates recent onset or intermittent symptoms and warrants urgent referral.

Pseudoesotropia is characterized by a wide nasal root and prominent but normal epicanthal folds. Little sclera shows medial to the corneas. The turn therefore seems most marked on gaze left or right, although the ocular axes are aligned.

Exotropia, or outward ocular deviation, is much less frequent in early infancy. At its outset, exotropia is usually intermittent, occurring with fatigue, fever, illness, or on first awakening. It may be difficult to elicit on casual examination.

• Clinical Pearl

Parents who report having observed a transient exotropia almost always are correct. Because it is intermittent, amblyopia is less likely to occur than constant misalignment. Delayed referral has no benefit.

Hypertropia or vertical misalignment occurs less frequently than horizontal misalignment. These two forms will frequently coexist. Most common is overaction on one or both inferior oblique muscles, resulting in an upward deviation of the adducted eye (toward the nose) in lateral gaze. Tilting of the head may correct the diplopia, in this instance simulating primary torticollis.

The provider must rule out ocular torticollis before considering any surgical intervention for torticollis.

• Clinical Pearl

Associated neurologic conditions, including myasthenia gravis, are more common with vertical strabismus than purely horizontal misalignment.

History and Physical Examination

The light reflex test (Hirshberg’s test) is helpful if strabismus is moderate to severe. To perform it properly, the child must gaze directly at the examiner’s light. The reflection should be in the same position in each pupil. If clearly lateral in one eye, that eye is esotropic. If clearly medial, that eye is exotropic. When in doubt, the provider should assume that misalignment exists. The clinician should then refer the child to an ophthalmologist who specializes in infants and children. Diagnosis is made by physical examination.

Management

Goals of management for strabismus include achieving the following:

Normal and equal vision

Cosmetically straight eyes

The highest achievable binocular cooperation

Despite anecdotal reports from patients or families, it is rare for a child to outgrow an evident eye turn. Newborns or infants may have occasional transient misalignment without concern, but any strabismus that is constant or frequent beyond ages 3 to 6 months warrants referral to an ophthalmologist.

Amblyopia

Pathology

Amblyopia is a unilateral or bilateral decrease in vision for which no cause is found on physical examination. It occurs when there is interference with sensory stimuli required for the development of normal binocular vision. This interference may result from blurring of an image, as for example from a transient corneal or lens opacity, a large refractive error, or strabismus. In the latter case, amblyopia derives from the adaptive adjustment made in the brain to avoid diplopia.

• Clinical Pearl

The younger the child with amblyopia is recognized and referred, the more likely corrective measures will successfully overcome the amblyopia. After age 3 or 4 years, the rate of treatment success diminishes with each passing year. By late childhood, amblyopia treatment is only rarely effective.

Management

Treatment modalities include the following:

Correction of any refractive error

Full-time or part-time occlusion of the normally fixing eye

Penalization or blurring of vision in the normally preferred or fixing eye to the point where the amblyopic eye has the better acuity. Penalization may be accomplished with spectacles, atropine or other accommodation blocking drops, or a blurring film applied to a spectacle lens.

Because early treatment may be successful in the vast majority of cases, early recognition of amblyopia and referral for initiation of therapy are critical. An eye injury, optic neuritis, or vascular occlusion later in life is devastating if the remaining eye is amblyopic.

NYSTAGMUS

Bilateral rhythmic oscillations of one or both eyes are termed nystagmus. When the movements are slow and sweeping, a retinal abnormality or other pathology causing diminished vision is more likely than when movements are rapid and jerky. Congenital nystagmus is often hereditary and may diminish with time and maturity. Most patients with congenital nystagmus are able to achieve 20/20 to 20/80 vision, with no visual consequences for school performance.

Acquired nystagmus is more frequently associated with significant neurologic abnormality. Imaging studies usually will be needed. Thorough pediatric ophthalmologic evaluation

is indicated in all cases of nystagmus; pediatric neurologic and otolaryngologist (ENT) consultation will be helpful in some instances.

is indicated in all cases of nystagmus; pediatric neurologic and otolaryngologist (ENT) consultation will be helpful in some instances.

LEARNING DISABILITY

A comprehensive eye examination by an ophthalmologist who is skilled in assessing a child with learning disability is a necessary part of evaluation of children who appear to have specific learning or reading problems. Occasionally, an oculomotor or visual impairment is present that spectacles can correct. Refer to the Chapter 21 for further discussion on the diagnosis and management of learning disability.

• Clinical Pearl

Almost universally, ophthalmologists believe that visual training is not helpful and may delay more effective educational strategies (AAP, 1998a). Defects in ocular function do not cause the neurologic problem of learning disability (Romanchuk, 1995; Silver, 1995).

The AAP shares this view and has stated so categorically based on scientific evidence (AAP, 1998a). Some optometric practitioners hold the opposite view, but their experience is anecdotal and not based on evidence.

ORBITAL PROBLEMS

Composed of processes of the cranial bones, the orbit may be malformed when premature closure of cranial sutures or other structural anomalies are noted. Neurologic and systemic abnormalities may coexist. Associated strabismus should be treated early to prevent irreversible amblyopia.

Exophthalmos and Proptosis

Exophthalmos and proptosis both describe forward protrusion of the eye. Benign dermoid tumors are a commonly encountered cause of orbital swelling in the pediatric population. They occasionally will cause proptosis but usually are found as discreet, rubbery, nontender lesions of the upper lid, more common temporally than medially. Growth may occur intermittently. Excision is generally elective. Small lesions require a small incision and therefore a smaller scar.

Hyperthyroidism can cause exophthalmos, especially in girls. Exophthalmos, however, occurs less frequently than in adulthood. Eyelid retraction is seen more typically and is an early indicator of the hyperthyroid state. Eyelid retraction can best be appreciated when examining the eye in the downward gaze component of examining the six cardinal fields of gaze. Refer to Chapter 60 for more information about assessing for exophthalmos.

Non–thyroid-related inflammation can cause the appearance of tumor. This type of presentation, also called orbital pseudotumor, may be unilateral or bilateral. Whether benign or malignant, orbital tumors are rare but do occur. They generally are of an acute or subacute onset. An acute onset of a pseudotumor can suggest cellulitis. An extension of sinusitis also may be part of the differential diagnosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree