Chapter 6 Complications of Therapeutic Minimally Invasive Intradiscal Procedures

Spinal pain that originates from the disc is thought to be a major cause of severe and chronic back pain.

Spinal pain that originates from the disc is thought to be a major cause of severe and chronic back pain. Discogenic pain may be caused by herniated and bulging discs, as well as internal disc disruption (IDD), which may be caused by annular tears that irritate small nociceptive nerve fibers within the outer layer of the annulus fibrosis.

Discogenic pain may be caused by herniated and bulging discs, as well as internal disc disruption (IDD), which may be caused by annular tears that irritate small nociceptive nerve fibers within the outer layer of the annulus fibrosis. People presenting with discogenic pain are typically treated with conservative modalities, including physical therapy, chiropractic care, proper activity performance, and antiinflammatory and over-the-counter medications.

People presenting with discogenic pain are typically treated with conservative modalities, including physical therapy, chiropractic care, proper activity performance, and antiinflammatory and over-the-counter medications. If conservative care fails to provide relief, other diagnostic and therapeutic modalities may be performed, including epidural steroid injections, selective nerve root blocks, discography, and facet-related interventions.

If conservative care fails to provide relief, other diagnostic and therapeutic modalities may be performed, including epidural steroid injections, selective nerve root blocks, discography, and facet-related interventions. However, if conservative diagnostic and therapeutic interventions do not alleviate discogenic pain, minimally invasive intradiscal procedures are often considered.

However, if conservative diagnostic and therapeutic interventions do not alleviate discogenic pain, minimally invasive intradiscal procedures are often considered. Some of these minimally invasive intradiscal treatments include chemonucleolysis, IDET, biacuplasty, Disc Dekompressor, nucleoplasty, percutaneous laser disc decompression, and injectable treatments such as methylene blue and tumor necrosis factor α. Each of these procedures addresses a key element in disc pathology.

Some of these minimally invasive intradiscal treatments include chemonucleolysis, IDET, biacuplasty, Disc Dekompressor, nucleoplasty, percutaneous laser disc decompression, and injectable treatments such as methylene blue and tumor necrosis factor α. Each of these procedures addresses a key element in disc pathology. Although some of these minimally invasive treatments are new and research is limited, they typically involve fewer risks and quicker recovery times compared with traditional open surgical practices.

Although some of these minimally invasive treatments are new and research is limited, they typically involve fewer risks and quicker recovery times compared with traditional open surgical practices. Minimally invasive intradiscal procedures are designed to lower risks, but as in any spine-related procedure, specific and sometimes catastrophic sequelae do occur.

Minimally invasive intradiscal procedures are designed to lower risks, but as in any spine-related procedure, specific and sometimes catastrophic sequelae do occur. Because these procedures penetrate the protective skin barrier and are placed near critical spinal structures, complications may include bleeding; nerve trauma; spinal cord injury; infection; and damage to vital structures, including vessels, nerve roots, vertebral endplates, the spinal cord, and organs.

Because these procedures penetrate the protective skin barrier and are placed near critical spinal structures, complications may include bleeding; nerve trauma; spinal cord injury; infection; and damage to vital structures, including vessels, nerve roots, vertebral endplates, the spinal cord, and organs. A potentially catastrophic type of infection from intradiscal procedure is discitis, or infection within the disc.

A potentially catastrophic type of infection from intradiscal procedure is discitis, or infection within the disc. Another potentially serious complication that may be related to infection is transverse myelitis, which involves inflammation of the spinal cord. It has been reported to occur in conjunction with chemonucleolysis.

Another potentially serious complication that may be related to infection is transverse myelitis, which involves inflammation of the spinal cord. It has been reported to occur in conjunction with chemonucleolysis. Allergic reaction can be caused by preoperative skin preparations, antibiotics, local anesthesia, and latex.

Allergic reaction can be caused by preoperative skin preparations, antibiotics, local anesthesia, and latex. Another complication of intradiscal procedures is bleeding in and around the spine, which can lead to epidural, subdural, muscular, and superficial hematomas.

Another complication of intradiscal procedures is bleeding in and around the spine, which can lead to epidural, subdural, muscular, and superficial hematomas. A common type of structural trauma associated with intradiscal procedures is a dural tear, or tearing of the outermost of the three meninges surrounding the spinal cord.

A common type of structural trauma associated with intradiscal procedures is a dural tear, or tearing of the outermost of the three meninges surrounding the spinal cord. Various intradiscal procedures use heat, leading to risk of heat damage to surrounding structures. One potentially serious complication that has been reported in conjunction with these high-heat intradiscal procedures is osteonecrosis, which may result in a painful fracture that requires surgery or percutaneous vertebral augmentation.

Various intradiscal procedures use heat, leading to risk of heat damage to surrounding structures. One potentially serious complication that has been reported in conjunction with these high-heat intradiscal procedures is osteonecrosis, which may result in a painful fracture that requires surgery or percutaneous vertebral augmentation. Physicians can hope to avoid complications associated with intradiscal procedures through extensive knowledge of anatomy, use of fluoroscopy and other visualization methods, and meticulous sterile technique, as well as administration of perioperative antibiotics.

Physicians can hope to avoid complications associated with intradiscal procedures through extensive knowledge of anatomy, use of fluoroscopy and other visualization methods, and meticulous sterile technique, as well as administration of perioperative antibiotics.Introduction

Chronic spinal pain is one of the most common reasons why people seek out medical attention. Between 70% and 90% of the population will experience back pain at some point in their lives,1,2 but thankfully, 80% to 90% of these people will recover from acute episodes with conservative therapy within 3 months.3,4 But for those who continue to suffer with chronic pain, performing activities of daily living can be excruciating. This ongoing turmoil leads to frequent absence from work, loss of employment, opioid dependence, and ever-increasing disability. Spinal pain that originates from the disc, or intradiscal pain, is thought to be a major cause of severe and chronic pain in this population. Over the past 50 years, researchers have been attempting to identify and treat the various sources of spinal pain. In fact, many procedures have been developed to identify the source of one’s pain. Some of the more commonly performed diagnostic procedures include medial branch blocks, selective nerve root blocks, and discography. After the source of one’s pain is located, disc-related procedures may be considered to relieve the pain.

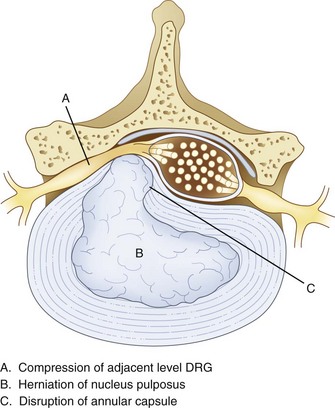

Surgery, typically involving laminectomy and microdiscectomy, has been shown to produce excellent clinical outcomes in patients with disc extrusion and neurologic deficits. However, patients with disc herniation smaller than 6 mm have fair or poor surgical outcomes.5 In addition, conventional open disc surgery can be associated with complications from general anesthesia, nerve damage, epidural fibrosis, chronic postoperative pain syndrome, and adjacent spinal instability. Intradiscal procedures aim to address key issues in disc pathology. Bulging, herniation, prolapse, and disc tears (internal disc disruption [IDD]) are some of the most common causes of spine pain. Disc bulging or herniation can cause pain, numbness, or weakness by mechanical irritation and compression of an adjacent nerve root. When this occurs, pain presents typically in a radicular pattern. Herniation is caused when fluid from the nucleus does not leak out of the annulus but bulges against it (Fig. 6-1). This can cause compression of nerve roots as well as stretching of annular fibers.

Various studies have shown that disc herniation disrupts the capsule around the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) (Fig. 6-1), allowing permeation of large molecules such as albumin, subsequently followed by edema, scarring, and inflammation.6 When an inflammatory reaction occurs, chemical irritation of an adjacent DRG or nerve root can occur, often causing axial or radicular pain.

Conversely, discogenic pain can occur without a disc bulge or prolapse. Such pain may originate from within the disc itself and is thought to be caused by tears and fissures in the annular layer of the disc.7 This type of pain is often called IDD or simply “discogenic pain” and is diagnosed by concordant pain on a provocative discography. IDD is believed to be caused by the lamellar fibers of the posterior annulus that are weaker than the anterior. This allows more flexion and extension of the lower lumbar spine but also predisposes the area to tears and herniations.8 Current thought suggests that discogenic pain may stem from irritation of small nociceptive nerve fibers within the outer third of the annulus fibrosis. The annulus is innervated by gray rami laterally, lateral ventral rami anteriorly, and sinuvertebral nerves posteriorly.9,10 People with nerve penetration deeper than the initial third of the annulus may be at higher risk for IDD pain problems.11 Additionally, as people age, the discs between the vertebrae lose water content and become brittle (degenerative disc disease).12 This can cause small tears in the annulus fibrosis, allowing some of the nucleus pulposus to leak out and causing irritation of the nociceptive fibers, local sympathetic nerves, and afferent nerve roots. Many irritating fluids are found within this space, including glycosaminoglycans and lactic acid. Pain signals also release irritating chemical mediators such as phospholipase A2, prostaglandin E, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), nitric oxide (NO), substance P, and many others.13–15

Disc-related pain from a disc herniation or IDD can take many forms. Pain can be sharp and shooting with radiation along a dermatomal distribution with corresponding magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) disc findings, or it can be more complex with radiation into other structures (e.g., groin pain from L5–S1). As we learn about pain pathways from nerve roots, the adjacent DRGs, the spinal cord, and the brain, our understanding of the complex pain patterns experienced by patients is growing. For instance, research has shown that pain signals from the lower lumbar discs travel from lower DRGs along the sympathetic nerves of the gray rami communicans to higher DRGs. There may also be a convergence of lower level lumbar disc-related pain signals to the L2 DRG.16,17 This may explain the nondermatomal pain patterns that some patients experience. Some treatments are now being directed at the DRG as opposed to intradiscal for discogenic pain from IDD.18–20 Another treatment consideration is use of an investigational device from Spinal Modulation, Inc., which offers hardware that applies DRG neurostimulation for pain relief.21

Disc pathology can also cause localized pain; for instance, discogenic low back pain is often described as “a belt of pain across my low back.” People presenting with these types of pain symptoms are typically treated with conservative care, including physical therapy, chiropractic care, proper activity performance, over-the-counter medications, and antiinflammatory medications.22 If conservative care fails to provide relief, imaging is typically performed at this stage if it has not already been done. If the disc is believed to be responsible for the pain symptoms, epidural steroid injections are often performed based on the imaging and patient’s pain pattern. Other diagnostic and therapeutic modalities may be performed based on the patient’s pain complaints. These treatments may include epidural steroid injections, selective nerve root blocks, discography, facet-related interventions, and others. If a patient fails to respond to conservative therapy and pain interventions, minimally invasive intradiscal procedures or surgery is often considered.

Review of Intradiscal Procedures

Chemonucleolysis

A study by Hoogland and Scheckenback23 supporting the efficacy of low-dose chemonucleolysis showed good or excellent results in 19 of 22 patients with obvious preoperative cervical disc herniation with predominantly radicular pain over a follow-up period of at least 1 year. In one patient, a fair result was obtained, and in two patients, the symptoms were unchanged; one of these patients subsequently underwent discectomy and anterior cervical spine fusion. No intra- or postoperative complications were noted. Furthermore, the authors of a review of 105 consecutive cases of chymopapain chemonucleolysis for single-level lumbar disc herniation concluded “the advantages of chemonucleolysis are well recognized.”24 Of the studies included in the review, mean follow-up was 12.2 years (range, 10 to 15.3 years). Eighty-seven patients were assessed using the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire during follow-up. An excellent or good response occurred in 58 patients (67%); four patients (4.5%) had a moderate response but were only minimally disabled. The treatment failed in 25 patients (28.5%), and 21 of them went on to surgery within a mean of 5.2 months (range, 3 weeks to 12 months). In 15 patients (71%), disc sequestration or lateral recess stenosis was found. Five of the remaining six patients had a large disc herniation at surgery. Surgery resulted in a significant improvement in nine cases. Discitis after chemonucleolysis occurred in six patients (5.7%). The authors of the review further concluded that chemonucleolysis is a safe and effective alternative to surgery in the treatment of herniated lumbar intervertebral discs in appropriately selected patients. The authors also noted chemonucleolysis appears to be a minimally invasive technique that has little traumatic effect on surrounding structures and is safer than surgery. They also remarked chemonucleolysis requires less operative time and postoperative hospital stay than discectomy and can be performed under local anesthesia, although all of the patients in this series had general anesthesia.

Intradiscal Electrothermal Therapy (Annuloplasty)

Intradiscal electrothermal therapy was first developed by Saal and Saal9 in 2000. The underlying theory is that intradiscal pain is caused by irritation of small nerves within the annulus fibrosis and that destroying those nerves will relieve the patient’s pain.9,25 IDET is designed to address the pain from annular tears, something very few procedures are designed to do. This procedure was meant to be a less invasive and safer alternative to spinal fusion for discogenic pain.

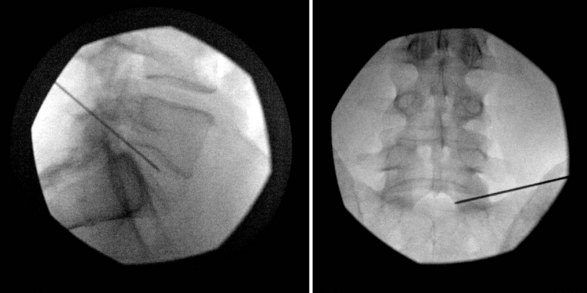

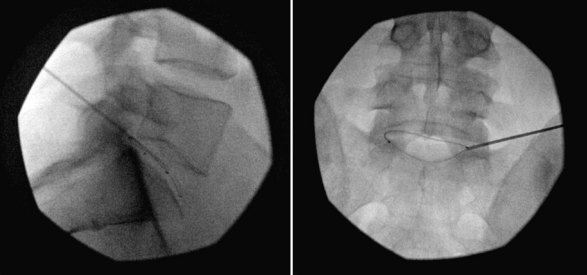

Intradiscal electrothermal therapy is performed under fluoroscopy and conscious sedation. It consists of a needle being inserted into the posterior lateral disc (Fig. 6-2) and a catheter being threaded into the disc (Fig. 6-3). This catheter has a special thermal coil that converts radiofrequency energy to heat. This coil is threaded through the disc in a circular fashion and is positioned adjacent to the tear or nerve distribution area in the posterior lateral aspect of the disc.3 Proper positioning is the key to a good result. The catheter should span the entire lesion and should be positioned near the pedicles on each side of the posterior annulus.26,27 Subsequently, the tip is heated, through radiofrequency, to 90°C, modifying the collagen matrix, and breaking the triple helix bonds, causing thickening, contraction, and a 10% decrease in disc volume.27 Heat is transferred through the coil to the surrounding tissues by conduction. The surrounding vascular areas act as a heat sink, preventing damage to tissues beyond the desired region.9,27 The heating seals the tear if present and causes thermal injury to all intradiscal nerve fibers in close proximity, effectively destroying pain transmission.27,28

The heating, thickening, and contraction process in IDET is believed to enhance the structural integrity of the disc, stabilizing intradiscal fissures and decreasing new nerve growth, although as of yet there are no studies to support this thought.9,26 However, studies using an electron microscope have been able to show visible shrinking of collagen molecules, giving credibility to this theory.27

Biacuplasty

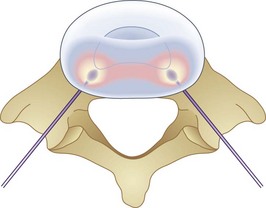

Biacuplasty is a newer technique developed by Baylis Medical to address intradiscal back pain produced by irritation of intradiscal nerve fibers.28,29 This procedure is considered by many to be safer than IDET because its bipolar design system allows for internal cooling of the radiofrequency transfer of heat between electrodes. The bipolar design pinpoints the area of treatment and prevents outside structures from being heated. Cooling is accomplished by running cool sterile water through an adjacent channel inside the probe. This prevents tissue closest to the probes from being scorched and protects spinal nerves outside the desired region from being heated by conduction through the hot probe. If needed, this system can treat an area of up to 4 cm.28,29 Unlike IDET, biacuplasty uses a lower temperature, at 40° to 50°C. This range is sufficient for thermoregulating nerves but may be insufficient for repairing annular tears, thus limiting its scope. The procedure consists of two radiofrequency probes placed under fluoroscopy posterior laterally into the annulus fibrosis with one on each side.29,30 Because the probes only need to be placed opposite each other, another advantage to this procedure is how easy it is to position the probes into the appropriate place. Whereas IDET requires threading a catheter and using fluoroscopy to make sure it is near the desired area, biacuplasty uses two adjacent probes coming from opposite sides of the vertebrae toward each other (Fig. 6-4), allowing for much easier placement.29,31

Subsequently, current is passed between the two probes, causing them to warm. The heat destroys the surrounding annular nerve fibers, and the probes are removed. Karaman et al30 and other physicians performing this technique recommend that patients wear an external stabilizing back brace for 6 to 8 weeks after the procedure to prevent injury to the area before stabilization of the disc can occur.29

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree