Chapter 10 Complications of Spinal Injections and Surgery for Disc Herniation

A detailed history and physical examination of the patient and review of pertinent diagnostic studies and laboratory values in order to identify patient-specific risk factors before intervention is critical.

A detailed history and physical examination of the patient and review of pertinent diagnostic studies and laboratory values in order to identify patient-specific risk factors before intervention is critical. Appreciation of the inherent interindividual variability in the location of critical structures and understanding of the anatomy of the planned procedural approach to the epidural space can help limit complications.

Appreciation of the inherent interindividual variability in the location of critical structures and understanding of the anatomy of the planned procedural approach to the epidural space can help limit complications. Use of fluoroscopic imaging (particularly with continuous fluoroscopy during the instillation of contrast) is essential unless otherwise contraindicated.

Use of fluoroscopic imaging (particularly with continuous fluoroscopy during the instillation of contrast) is essential unless otherwise contraindicated. Strict maintenance of aseptic technique, with consideration toward wearing a mask in addition to sterile gloves, will minimize the risk of infectious complication.

Strict maintenance of aseptic technique, with consideration toward wearing a mask in addition to sterile gloves, will minimize the risk of infectious complication.Introduction

Back pain is among the most common pain-related complaints that lead patients to seek care from physicians. Underlying disc herniation and subsequent radicular symptoms from direct compression of nerve roots or inflammatory mediators related to disc disruption are a frequent cause of the pain leading to these physician visits. The expenditure on care for these patients has been rapidly increasing over the past several years, and one recent study estimates that total health care expenditures for adults with back and neck pain increased by 82% in the United States between 1997 and 2006.1 These costs are attributable to a variety of diagnostic and treatment measures instituted for the alleviation of patient suffering, and a large portion of the costs is clearly related to interventional therapies for back pain such as epidural injections and surgery.

Epidural steroid injections (ESIs) are a commonly instituted therapy for degenerative disc disease with radicular symptoms. The utilization of this type of therapy has also increased substantially in recent years.2 In the same time period, there has been a similarly substantial increase in lumbar surgeries of which lumbar discectomy is the most commonly performed for patients with disc herniation causing lumbar radicular symptoms.3,4 With use of any medical therapy (both pharmacologic and interventional), there is always a degree of risk to the patient, and a comprehensive knowledge of the nature of that risk is paramount to minimizing complications to the greatest extent possible.

Complications of Epidural Steroid Injections

Epidural steroid injections are performed by one of three general techniques: interlaminar, transforaminal, and caudal. The interlaminar and transforaminal approaches are applied in the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine for radicular symptoms in the upper and lower extremities, respectively. The caudal approach is, for obvious reasons, only applicable for lumbar radicular symptoms. There is variability in which approach is used to treat cervical or lumbar radicular symptoms between the interlaminar and transforaminal route among interventional pain medicine specialists. The transforaminal approach is advocated to better direct the deposition of corticosteroids at the location of pathology, which is within the neural foramen. However, as discussed later, this anatomic location is also occupied by critical arterial vascular structures that can be inadvertently entered or injured during the injection. The interlaminar approach, on the other hand, is advocated to be safer because of the decreased risk of intraarterial injection and being more in line with the approach used to provide epidural analgesia as an established skill set of the many practitioners who enter pain medicine from anesthesiology backgrounds. Caudal access to the epidural space is among the earliest described methods of providing ESIs and is used by many practitioners as their primary method of administering ESIs for patients with lumbosacral radiculopathy.5 It has an added advantage as well in patients with previous lumbar laminectomy that can make accessing the epidural space from other routes more challenging, particularly from an interlaminar approach.

Broadly speaking, as seen in Table 10-1, the potential complications of ESIs can be differentiated into the following categories: (1) medication reactions, (2) vascular injury or intravascular injection, (3) bleeding, (4) infection, (5) needle trauma (including dural puncture), and (6) miscellaneous.

Table 10-1 Potential Complications of Epidural Steroid Injections

| Category of Complication | Example |

|---|---|

| Medication reactions | Allergic reaction, local anesthetic toxicity, steroid effect |

| Vascular injury or intravascular injection | Artery of Adamkiewicz, vertebral artery |

| Bleeding | Epidural hematoma |

| Infection | Epidural abscess, meningitis |

| Needle trauma | Spinal cord injury, nerve root injury, dural puncture |

| Miscellaneous | Urinary complications, vasovagal reactions |

Medication Reactions

During a typical ESI, three types of medications are administered: a local anesthetic, a corticosteroid preparation, and a contrast agent. Reactions to these medications can be either allergic in nature or related to the known pharmacology of the drugs themselves (Table 10-2).

Table 10-2 Medication Reactions in Epidural Steroid Injections

| Medication | Potential Reaction | Serious Complications |

|---|---|---|

| Local anesthetics | Toxicity | Seizure, cardiac arrest |

| Corticosteroids | Physiologic effects | Hyperglycemia, fluid retention, Cushing syndrome |

| All medications commonly used in epidural steroid injections (local anesthetics, corticosteroids, contrast agents) | Allergic reaction | Anaphylaxis |

With respect to allergic reactions, there is a known incidence of allergy to all of the aforementioned medications used in ESI. In terms of local anesthetics, the most frequently used in the context of ESI are the amide local anesthetics lidocaine and bupivacaine. Allergy to amide local anesthetics is quite rare and usually a contact dermatitis reaction, but it can occasionally be an anaphylactic-type reaction.6 In one such case report of an anaphylactic-type reaction to amide local anesthetics, a patient without a known history of local anesthetic allergy developed an anaphylactic response to lidocaine and bupivacaine administered during a lumbar injection (presumably an ESI, although the report does not mention the exact procedure performed) after two uneventful injections with the same agents previously.6 Corticosteroid preparations have also been reported to cause allergic reactions when administered epidurally, and although symptoms are most frequently seen immediately after administration, they can result in a delayed onset of symptoms up to several hours later.7 Contrast allergy, particularly to iodinated contrast agents, is also reported in the literature, although life-threatening anaphylactic reactions are rare.8 Reported factors that increase the risk of reaction to contrast agents include a history of previous reaction to contrast agent, asthma, atopy, and advanced heart disease.9

Toxicity associated with local anesthetic administration is exceedingly rare with doses commonly administered during ESIs and is more frequently seen with other interventional procedures used in pain medicine (e.g., sympathetic blockade). Inadvertent intravascular injection of local anesthetics into the vertebral artery during a cervical transforaminal ESI, however, has been reported to cause seizures (and even death) at lower doses of local anesthetic than those typically reported to cause seizures when administered intravenously.10 Presumably, the direct access to the cerebral circulation increases the risk of seizure from inadvertent intravascular administration of local anesthetics in the cervical spine.

Vascular Injury and Intravascular Injection

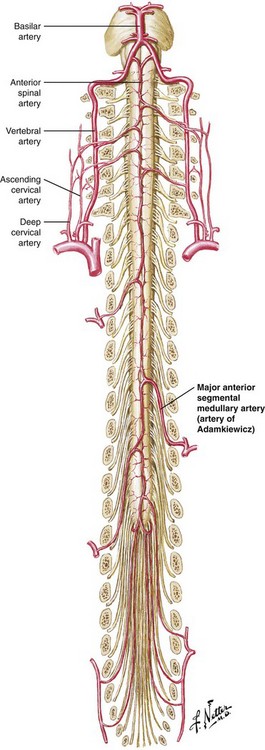

The vascular supply to the spinal cord is commonly understood to consist of paired posterior spinal arteries and a single anterior spinal artery, the latter supplying the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord. The anterior spinal artery has additional vascular supply from radiculomedullary arteries as it progresses caudally along the spinal cord. In the cervical spine, there is an average of three such radiculomedullary arteries that originate from branches of the vertebral arteries and occasionally have contributions from the ascending and deep cervical arteries as well.11,12 Progressing more caudally, the supply to the anterior spinal artery is more limited, with the primary contribution arising from the artery of Adamkiewicz, a radiculomedullary artery of variable anatomic origin. Most commonly (reportedly 85% of the time), this artery arises between T9 and L2, and 80% of the time, it is located on the left.13 See Fig. 10-1 for a representation of this blood supply.

Because the blood supply to the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord is dependent primarily on a few radiculomedullary arteries, with the low thoracic cord dependent on a single radiculomedullary artery (the artery of Adamkiewicz), injury to or embolization of any of these arteries can lead to a catastrophic neurologic outcome. Anatomic variation in the location of these arteries compounds the risk and should lead to vigilance in the performance of transforaminal injections. Indeed, there are reports in the literature of paraplegia and anterior spinal artery syndrome resulting from presumed embolism or injury to the artery of Adamkiewicz at almost all lumbar levels with one case as low as S1.11,14

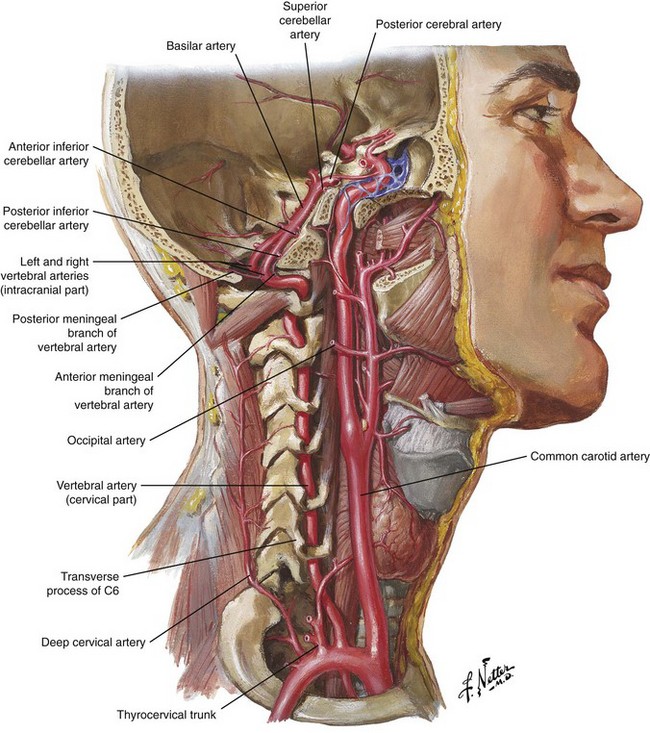

In the cervical spine, as seen in Fig. 10-2, the vertebral artery is found anteriorly within the foramen most frequently at C6 and above.12 Injury to this structure is also associated with catastrophic outcomes, as was reported in one case in which autopsy revealed that a puncture of the vertebral artery during a C7 transforaminal ESI led to a dissection and eventual thrombosis of the artery, causing death of the patient.15 Multiple reports can be found in the literature of brain infarction and spinal cord infarction associated with the transforaminal approach to cervical ESIs with the postulated mechanisms being embolism of particulate steroid particles versus direct injury to the vertebral or radiculomedullary arteries supplying the anterior spinal artery, respectively.10,15–20

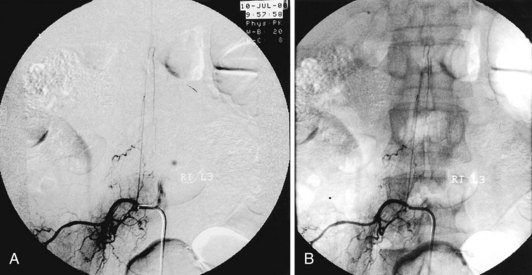

Avoiding these devastating complications is a primary procedural challenge facing interventional pain physicians. With respect to avoiding intravascular injection and subsequent embolic phenomena, it appears that the use of live fluoroscopy (with digital subtraction if available) is an essential step, particularly with the transforaminal approach, even though it may not be 100% effective. Fig. 10-3 illustrates the benefits of digital subtraction angiography in this image that shows the artery of Adamkiewicz in a spinal angiogram at the L3-L4 level. Use of intermittent fluoroscopy (in lieu of live, continuous fluoroscopy) during contrast injection can cause the proceduralist to miss the appearance of vascular uptake.21,22 In addition, it should be noted that a recent study showed an 8.9% incidence of simultaneous epidural and vascular patterns on injection of contrast during lumbar transforaminal injections, a finding that reinforces the critical importance of diligence during contrast injection in transforaminal ESIs, particularly when one considers that a radiculomedullary artery supplying the anterior spinal artery can occur at almost any vertebral level.23

The nature of the agent injected also can be a factor in the outcomes of inadvertent intravascular injection. A study by Tiso et al24 looked at the role of particulate corticosteroids through analysis of particulate size and microscopic characteristics of the particles. In sum, they found that triamcinolone and methylprednisolone had a tendency to form aggregates in excess of 100 µm (which may increase the risk of vascular occlusion after intravascular injection) and recommend that in the case of cervical transforaminal ESIs, that only corticosteroid solutions (dexamethasone and betamethasone sodium phosphate) be used. This sentiment is further supported by review performed by Scanlon et al10 who note that thus far all of the commonly used corticosteroids have been associated with brain or spinal cord infarction except dexamethasone.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree