Chapter 17 Complications of Percutaneous Vertebral Augmentation

Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty

Painful VCFs caused by osteoporosis and malignancy are seen more frequently as the U.S. population ages and life expectancies increase.

Painful VCFs caused by osteoporosis and malignancy are seen more frequently as the U.S. population ages and life expectancies increase. Because VCFs can cause debilitating problems, including spinal deformity, impairment of locomotion, decreased lung function, heightened risk of subsequent fracture, and increased mortality, treatment is essential to inhibit the development of deleterious sequelae.

Because VCFs can cause debilitating problems, including spinal deformity, impairment of locomotion, decreased lung function, heightened risk of subsequent fracture, and increased mortality, treatment is essential to inhibit the development of deleterious sequelae. PVA collectively refers to vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, two minimally invasive procedures used to treat VCFs.

PVA collectively refers to vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, two minimally invasive procedures used to treat VCFs. Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty involve injection of medical-grade orthopedic cement into damaged, painful vertebral bodies. Whereas kyphoplasty incorporates the use of a balloon to expand the injection site before introduction of the orthopedic cement, vertebroplasty involves injection of cement directly into the collapsed vertebrae without balloon pretreatment.

Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty involve injection of medical-grade orthopedic cement into damaged, painful vertebral bodies. Whereas kyphoplasty incorporates the use of a balloon to expand the injection site before introduction of the orthopedic cement, vertebroplasty involves injection of cement directly into the collapsed vertebrae without balloon pretreatment. The primary goal of PVA is to reduce the pain associated with VCFs. Secondary goals may include stabilization of crumbling vertebrae and prevention of further vertebral collapse, reversal of height loss (height restoration), and correction of kyphotic deformities that result from VCFs.

The primary goal of PVA is to reduce the pain associated with VCFs. Secondary goals may include stabilization of crumbling vertebrae and prevention of further vertebral collapse, reversal of height loss (height restoration), and correction of kyphotic deformities that result from VCFs. Because of their minimally invasive nature, PVA procedures carry a lower risk of complications than more invasive interventions such as open surgery. However, PVA procedures are associated with serious risks, including errant needle placement, cement extravasation, side effects related to the procedure (e.g., adjacent level fractures), infection, and risks from anesthesia.

Because of their minimally invasive nature, PVA procedures carry a lower risk of complications than more invasive interventions such as open surgery. However, PVA procedures are associated with serious risks, including errant needle placement, cement extravasation, side effects related to the procedure (e.g., adjacent level fractures), infection, and risks from anesthesia. Complications in vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty may be minimized by careful patient selection and by obtaining adequate training and using meticulous technique.

Complications in vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty may be minimized by careful patient selection and by obtaining adequate training and using meticulous technique.Introduction

Worldwide approximately 1.4 million persons currently have vertebral compression fractures (VCFs),1 which are caused predominantly by osteoporosis and malignancy. The incidence of painful VCFs is increasing as age and life expectancy increase.

Osteoporosis, the leading cause of VCFs, is the most common metabolic bone disorder in the United States, affecting 25 million people and leading to approximately 750,000 new osteoporotic vertebral fractures each year.2,3 Of these, only one-third receive treatment,4 and more than one-third become chronically painful.2 Annualized direct care expenditures for osteoporotic fractures in the United States were estimated to range from $12 billion to $18 billion in 2002.5

Bone malignancy, another leading cause of VCFs, is a consequence of cancer, the second leading cause of death in the United States. Roughly two-thirds of cancer patients develop metastases,6,7 and vertebral body metastases occur frequently in systemic malignancy. In fact, the skeletal system is the third most common site of metastasis, and metastases favor the spine.8

Vertebral compression fractures can cause debilitating spinal deformity with possible impairments in locomotion,9,10 decreased lung function,11 a heightened risk of subsequent fracture,12 and increased mortality.13,14 Therefore many believe expert and efficacious treatment of VCFs is essential to inhibit the development of deleterious sequelae.

Although vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty are similar procedures with largely analogous methodologies and objectives, the chief distinction between them is that kyphoplasty incorporates a balloon to expand the injection site before introduction of orthopedic cement, while vertebroplasty involves injection of cement directly into the collapsed vertebrae without balloon pretreatment. The addition of balloon pretreatment may permit greater gains in vertebral height and kyphosis correction than are achievable with vertebroplasty.15 Because of the publication of numerous studies that suggest kyphoplasty may have greater efficacy than vertebroplasty, some practitioners consider kyphoplasty to be superior to vertebroplasty for the correction of painful VCFs.16 However, there exists a comparable number of studies that suggest vertebroplasty is as efficacious as kyphoplasty in stabilizing vertebral fractures and correcting attendant pain and other related consequences. Furthermore, the higher cost associated with kyphoplasty and the outpatient nature of vertebroplasty have made vertebroplasty a more attractive treatment option in many cases.17

Vertebroplasty

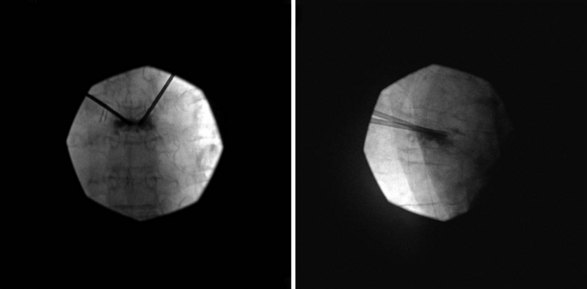

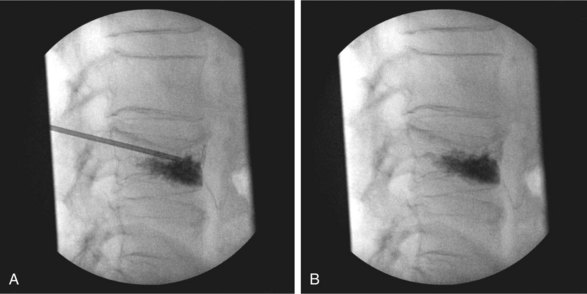

Bone cement may be mixed with antibiotic and barium or tantalum to reduce the risk of infection and facilitate fluoroscopic visibility. Normally, a transpedicular approach is used to access the central portion of the vertebral body in the thoracic and lumbar spine because this spares the spinal canal or segmental arteries flanking the vertebral body. The procedure can be done with an extrapedicular approach as well but may not have as robust of a safety profile. Vertebroplasty can be done unilaterally or bilaterally as desired by the performing surgeon (Figs. 17-1 and 17-2). Some experts do recommend a bilateral approach because they believe that this provides increased safety through redundancy and ensures central placement of cement. No current prospective studies have clearly defined the most efficacious method of these two approaches.

Kyphoplasty

Kyphoplasty is a newer therapy indicated for the treatment of painful VCFs. Kyphoplasty parallels vertebroplasty in that it is highly effective in relieving pain associated with VCFs. However, several studies suggest that kyphoplasty can also restore height and reduce deformity compared with vertebroplasty.18 The data are not completely clear, however, because one study found that kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty produce the same degree of height restoration,19 although a later cadaver study by the same group20 found the increase in vertebral height was greater with kyphoplasty than with vertebroplasty (5.1 mm vs. 2.3 mm, respectively).

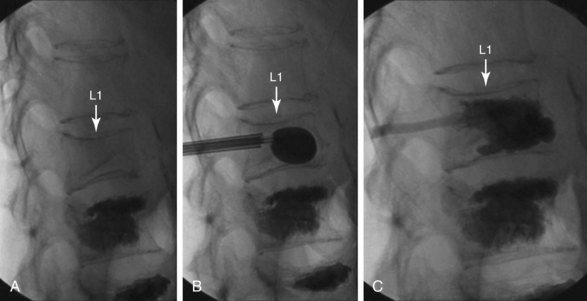

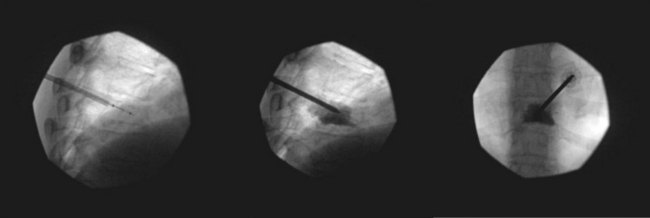

Normally, kyphoplasty is performed under intravenous (IV) sedation or monitored anesthesia care, but some practitioners prefer to do the procedure with general anesthesia. As in vertebroplasty, fluoroscopy (or CT scan) is used to guide the procedure. Typically, a small incision is made, and the trocars are advanced bilaterally into the vertebral body using a transpedicular approach (Fig. 17-3). Kyphoplasty can also be done via an extrapedicular approach, and some systems advocate a unilateral approach (Fig. 17-4). When the trocars are in the correct position, a cannulated drill is placed through the trocar, and the bone is drilled by hand creating space within the vertebral bodies for the balloons. The drill is then removed, and the balloons (inflatable bone tamps) are inserted through the trocars. The balloons are filled with contrast medium and carefully inflated under live radiography for easy visualization. Subsequently, the balloons are inflated until they expand to the desired height and then removed, leaving prearranged cavities for the cement within the fractured vertebral body. This process is what is thought to provide the height restoration for the procedure. The cavities are then filled with the same type of orthopedic cement used in vertebroplasty, and the trocars removed. Because of its widely promoted height-restoration effects, many physicians recommend kyphoplasty over vertebroplasty. It should be noted, however, that kyphoplasty is far more expensive a procedure, potentially costing significantly more than vertebroplasty. Clinicians are in need of prospective comparative studies that match these two modalities of treatment to specific types of fractures.

Indications and Contraindications

The vertebral compression associated with osteoporosis results from lowered bone strength, a consequence of accelerated loss of bone minerals. Furthermore, kyphosis secondary to osteoporotic VCF shifts the center of gravity anteriorly, increasing the risk of falls and additional fractures. In conjunction with physiologic decreases in lung capacity and appetite, a significant increase in 1-year mortality is associated with a patient’s first VCF.14

Absolute contraindications to vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty are rarely seen but include:

Relative contraindications for PVA treatments include:

Neoplastic disease (epidural or intradural) that compresses or encases the thecal sac or nerve roots

Neoplastic disease (epidural or intradural) that compresses or encases the thecal sac or nerve rootsBenefits

In the literature, vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty have been described as bringing significant pain relief to patients with vertebral fractures secondary to osteoporosis and solid or marrow-based malignancy (80% to 89% in most reports). For most, relief is usually immediate after treatment, with maximal effect obtained as soon as 2 weeks after treatment. According to one systematic review of the literature, there is fair evidence (level II to III) that 2 years after the intervention, vertebroplasty provides a similar degree of pain control and physical function as optimal medical management. There is also fair evidence (level II to III) that kyphoplasty results in greater improvement in daily activity, physical function, and pain relief compared with optimal medical management for osteoporotic VCFs 6 months after the intervention.21 Furthermore, a meta-analysis of the literature examining pain relief and complications in vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty patients in 1036 studies found that both vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty provided significant pain improvement as measured by visual analog scores (VAS); vertebroplasty produced greater improvement in VAS scores than kyphoplasty but also carried a statistically greater risk of cement leakage and new fracture.22

In addition, the pain relief from both procedures has been noted as long lasting as demonstrated in studies with multiyear follow-ups.23,24 One such multiyear study, a retrospective single-center consecutive case series with 2-year follow-up, found kyphoplasty markedly improved clinical outcome and produced significant vertebral height restoration and normalization of morphologic shape indices that remained stable for at least 2 years after treatment.25 Pain scores, patient ability to ambulate independently and without difficulty, and need for prescription pain medications improved significantly after kyphoplasty and remained unchanged or improved at 2 years; furthermore, vertebral heights significantly increased at all postoperative intervals, with greater than or equal to 10% height increases in 84% of fractures. Asymptomatic cement extravasation occurred in 11.3% of fractures, and during the follow-up period, additional fractures occurred in previously untreated levels at a rate of 4.5% per year. There were no kyphoplasty-related complications.

Numerous studies have examined the specific benefits of kyphoplasty. For example, a randomized, controlled trial of 300 patients at 21 sites in eight countries noted significant improvement in quality of life in kyphoplasty patients over the control group as assessed by short form physical component summary.26 Additionally, a study in 314 kyphoplasty recipients with VCFs as a result of osteoporosis or multiple myeloma found that all patients tolerated the kyphoplasty procedure well, the average Owestry Disability Index score decreased by 12.6 points, and there was no statistically significant difference with regard to functional outcome in the osteoporosis and multiple myeloma subgroups.27 And a study in 555 patients with a total of 1150 vertebral fractures treated with kyphoplasty noted no cement-related complications as described in the literature and concluded by careful interdisciplinary indication setting and a standardized treatment model that kyphoplasty presented a safe and effective procedure for the treatment of various vertebral fractures.28

Despite numerous studies in the literature that support the efficacy of PVA, two controversial original articles questioning the worth of vertebroplasty were published in the August 6, 2009, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. These included reports by Kallmes et al29 on the Investigational Vertebroplasty Safety and Efficacy Trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00068822) and Buchbinder et al30 on a randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures (Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry number, ACTRN012605000079640). In both studies, the authors concluded that vertebroplasty has no greater benefit than placebo in the treatment of painful osteoporotic compression fractures.

Kallmes et al29 reported, “Improvements in pain and pain-related disability associated with osteoporotic compression fractures in patients treated with vertebroplasty were similar to the improvements in a control group.” In this multicenter trial, 131 patients with one to three painful osteoporotic VCFs underwent either vertebroplasty or a simulated procedure without cement (control group). The primary outcomes were scores on the modified Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire (RDQ) (on a scale of 0 to 23, with higher scores indicating greater disability), and patients’ ratings of average pain intensity during the preceding 24 hours at 1 month (on a scale of 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating more severe pain). Patients were permitted to cross over to the other study group after 1 month. All patients underwent the assigned intervention (68 vertebroplasties and 63 simulated procedures). The baseline characteristics were similar in the two groups. At 1 month, it was reported that there was no significant difference between the vertebroplasty group and the control group in either the RDQ score or the pain rating. Both groups had immediate improvement in disability and pain scores after the intervention. Although the two groups did not differ significantly on any secondary outcome measure at 1 month, there was a trend toward a higher rate of clinically meaningful improvement in pain (a 30% decrease from baseline) in the vertebroplasty group (64% vs. 48%; P = .06). At 3 months, there was a higher crossover rate in the control group than in the vertebroplasty group (43% vs. 12%; P < .001), according to the report.

The Buchbinder et al30 report described a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in which participants (n = 78) had one or two painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures that were of less than 12 months’ duration and unhealed, as confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and randomly assigned to undergo vertebroplasty or a sham procedure. Participants were stratified according to treatment center, sex, and duration of symptoms (<6 weeks or ≥6 weeks). Outcomes were assessed at 1 week and at 1, 3, and 6 months. The primary outcome was overall pain (on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being the maximum imaginable pain) at 3 months. Buchbinder et al30 reported they found no beneficial effect of vertebroplasty compared with a sham procedure in patients with painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures at 1 week or at 1, 3, or 6 months after treatment. They noted that vertebroplasty did not result in a significant advantage in any measured outcome at any time point, although there were significant reductions in overall pain in both study groups at each follow-up assessment. Similar improvements were seen in both groups with respect to pain at night and at rest, physical functioning, quality of life, and perceived improvement.

In response to these original articles, proponents of vertebroplasty submitted correspondence that critiqued the studies. One group of respondents31 expressed “serious concerns” over both trials, noting that the study by Kallmes et al29 involved outpatients exclusively and excluded inpatients hospitalized with acute fracture pain. The same group of commentators noted that the study protocol mandated 4 weeks of medical therapy before enrollment, which they maintained resulted in a study on healed rather than subacute fractures, and noted a more appropriate selection criterion would have been uncontrolled pain for fewer than 6 weeks. They also noted that the Buchbinder et al30 trial included an inadequate number of patients for a subgroup analysis, substantially limiting statistical power, and that although the study is described as a multicenter trial, two of the four hospitals withdrew early from the study after enrolling five patients each. The authors of the correspondence also argued that 68% of the procedures were performed in one hospital by one radiologist, and the rates of eligible patients who declined to participate were 64% in the Buchbinder trial30 and 70% in the Kallmes trial29 (85% in the United States), raising further concerns regarding patient selection.

Another group of correspondents32 noted that patients with maximal back pain, who tend to have the greatest improvement in pain score after vertebroplasty, would also be the least likely to participate in such studies because they would risk being randomly assigned to the placebo group, as evidenced by the preprocedural pain scores among patients who were enrolled. The correspondents also commented that neither study was sufficiently powered to perform subanalyses, particularly on patients with certain types of fractures that would be more likely to have improved pain scores after vertebroplasty (e.g., those with gas-filled clefts and pathologic fractures).

Also, a singleton respondent33 questioned whether a group of patients who receive an injection of an anesthetic should be considered a true control because delivery of a local anesthetic can have beneficial effects for a period exceeding the activity of the drug. He also suggested that there may be a significant difference in crossover rates between the treatment and control groups (12% vs. 43%) in the study by Kallmes et al,29 which could suggest patient dissatisfaction with the sham procedure that was not fully captured by pain scales.

Certainly, these criticisms provide compelling reasons to question the results of the controversial Kallmes et al29 and Buchbinder et al30 studies. Furthermore, it should be noted that these two studies compete with a vast pool of published evidence that supports the therapeutic legitimacy of PVA.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree