6 Complications of Common Selective Spinal Injections

Prevention and Management

Selective spinal injections are being performed with increasing frequency in the management of acute and chronic pain syndromes.1–3 Because these procedures require placing a needle in or around the spine, a risk of complications is always present. Therefore, knowledge about prevention of complications, and early recognition and management when they do occur, are paramount to appropriate patient care. This requires adequate physician training and appropriate patient preparation and monitoring. This chapter will discuss physician training, patient preparation and monitoring, and specific complications and their treatment (Appendix II).

Physician Training

Although it is true that uncomplicated lumbar procedures (in an otherwise healthy population) do not require the degree of training and expertise that high-risk procedures performed in a medically unstable population do, certain standards must still be met. Currently, the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPM&R) has adopted guidelines that recommend a minimum level of documented didactic and clinical training in complication prevention, recognition and management, spinal injection technique, and patient selection, such as that provided in an appropriate fellowship or residency program.4 This program must provide specific training in spinal injections and the recognition, prevention and treatment of related complications; and advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) certification.

Patient Preparation

Patient preparation issues include patient education,5,6 informed consent statement, NPO (nil per os; “nothing by mouth”) status, IV access, certainty that no procedural contraindications exist, patient positioning, sterile preparation and draping, supplemental intravenous (IV) fluids and oxygen, and plans for appropriate recovery following the procedure. Depending on the procedure and patient status, prophylactic antibiotics may also be included.

Patient education should include a thorough description of the procedure, including potential risks, benefits, alternatives, and likely outcomes.6 An informed consent statement, confirming the conversation, should be executed. The statement should include signatures of the patient, the doctor, and a witness.

Prior to the procedure, the patient should be NPO for 12 hours for solid foods and for 8 hours for fluids, preoperatively, to ensure that all gastric contents are distal to the ligament of Treitz.7

If the patient has coexisting medical problems (e.g., has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], heart disease, etc.), clearance from the patient’s primary care or specialty doctor should be obtained. Depending on the patient’s problem, preprocedure laboratory work may include a complete blood count with differential diagnosis, liver function tests, urinalysis, chest radiograph, ECG, blood culture and sensitivity, urine culture and sensitivity, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Care must be taken to ensure there is no region of neural compression or stretch, particularly if sedating medication will be used. Areas that are particularly vulnerable to neural compression or stretch include the ulnar nerve at the elbow and the brachial plexus.8 If necessary, use an arm board, tape, strapping or padding to make the patient more comfortable, enable him or her to hold the appropriate position, and prevent the patient’s hands from inadvertently compromising the sterile field.

General Complications of Spinal Injections

Infectious Complications

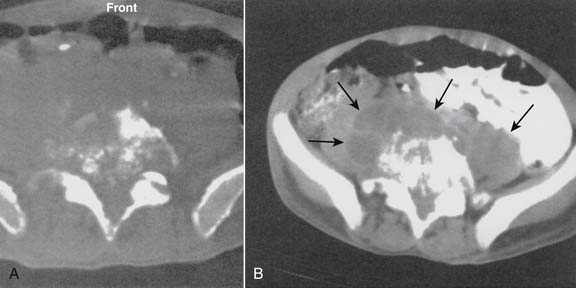

Infections, ranging from minor to severe conditions such as meningitis,9,10 epidural abscess,11–13 and osteomyelitis (Figs. 6-1 and 6-2),14,15 occur in 1% to 2% of spinal injections. Severe infections are rare and occur in from 1 in 1000 to 1 in 10,000 spinal injections. Severe infections may have far-reaching sequelae, such as sepsis, spinal-cord injury, or spreading to other sites in the body via Batson plexus or direct contiguous spreading. Poor sterile technique is the most common cause of infection. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common offending organism causing infection from skin structures.

If the infection appears to progress to spinal structures or spaces, or if the patient is infirm or otherwise predisposed to infection, in-patient evaluation and care with appropriate IV antibiotics is usually required. If epidural abscess occurs, emergent surgical drainage must be considered to avoid neural damage or other complications.16 Early detection and treatment of epidural or intrathecal infection is necessary to avoid morbidity and mortality. It usually manifests with severe back or neck pain, fever, and chills, with a leukocytosis developing on the third day following the injection.13

Cardiovascular Complications

Bleeding is a risk inherent to all injection and surgical procedures. The potential for bleeding during spinal injection is increased by liver disease, the consumption of warfarin or other anticoagulants,5,17,18 certain inherited anemias (such as G6PD deficiency or sickle-cell anemia), coagulopathy from any cause, and venous puncture.

The epidural vasculature is injured in 0.5% to 1% of spinal injections on average, and is more common with placement of the needle in the lateral portion of the spinal canal than the midline.19 Significant epidural bleeding may cause the development of an epidural hematoma. Clinically-significant epidural hematomas are rare, with a reported incidence of less than 1 in 4000 to 1 in 10,000 lumbar epidural cortisone injections; and may lead to irreversible neurologic compromise if not surgically decompressed within 24 hours.19–25 Retroperitoneal hematomas may occur following spinal injection if the large vessels are inadvertently penetrated. These hematomas are usually self-limited but may be a cause of acute hypovolemia or anemia. In addition to bleeding, a variety of dysrhythmias may occur. When a dysrhythmia occurs, treatment should be initiated immediately. The entire team of primary care physicians (PCPs) must be able to function synergistically when treating a dysrhythmia.

ACLS code scenarios should be run in the procedure facility no less than quarterly; all PCPs should know how to alert other staff and extended PCPs immediately; and everyone should know their specific roles in such situations. In addition, all PCPs should know where emergency care equipment is located and how to use it within the limits of their roles. Treatment of individual dysrhythmias is beyond the scope of this chapter; however, the reader is directed to the Emergency Cardiac Care Algorithms included in Appendix I and other sources for more detailed information.26,27

Neurologic Complications

Studies demonstrate that fluoroscopically-guided spinal injections are less apt to cause inadvertent neural injury or injection into a vascular structure.28 A pertinent neurologic review of symptoms and a physical examination should be performed immediately if a neurologic complication is suspected.

Respiratory Complications

Respiratory arrest occurs when a patient becomes apneic for greater than 1 minute, due to lack of central respiratory drive or paralysis of the muscles of respiration.29 Respiratory arrest may occur from a variety of causes, including oversedation, central nervous system trauma, and intrathecal or epidural injection of a sufficient amount of local anesthetic to cause spinal anesthesia.

The true incidence of respiratory depression due to spinal opioid administration is unknown. Factors that may cause respiratory depression include the use of sedatives, parenteral or spinal opioids, and local anesthetics. One of the main advantages of spinal versus parenteral opioid administration is the lack of respiratory depression with the former.30 It should be emphasized that respiratory rate alone is inadequate to establish the presence or lack of respiratory depression. The measurement of blood gases remains the preferred option.29

When a pneumothorax does occur, it is usually self-limited and causes only minor collapse(s) of the lung (10%).31 Treatment includes close observation with supportive care, usually in a hospital, and serial chest radiographs. A chest tube should be placed if the pneumothorax advances significantly over 25% or the patient develops shortness of breath or other signs of respiratory distress.

Urological Complications

The application of local anesthetics and/or opioids to the lumbar and sacral nerve roots results in higher incidence of urinary retention.32 This side-effect of lumbar epidural nerve block is seen more commonly in elderly males, multiparous females, and patients who have undergone inguinal and perineal surgery. Overflow incontinence may occur if such a patient is unable to void or bladder catheterization is not utilized. All patients undergoing lumbar epidural nerve block should demonstrate the ability to void the bladder prior to discharge from the pain center.

Dural Puncture

In the hands of the experienced interventional spine specialist, inadvertent dural puncture during lumbar epidural injections should occur in <0.5% of cases (or 1 in 200 epidural injections).33 This occurs when the dura mater is violated by the epidural needle, and a sufficient amount of cerebrospinal fluid leaks out from the thecal sac, causing a positional headache.34–37 The rare occurrence of postdural puncture (spinal-tap) headache is an annoying side effect, but is generally benign for the most part and will pass without permanent harm or morbidity to the patient.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree