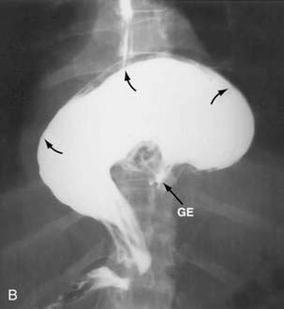

Fig. 8.1

Types of paraesophageal hernias. Source Schenarts et al. [46, Fig. 16.1], with permission of Springer

Diagnostics Evaluation

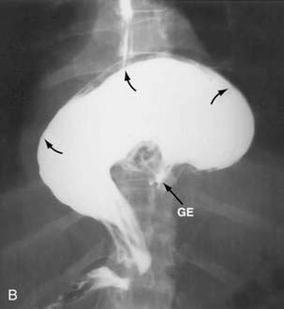

Patients experiencing acute paraesophageal incarceration/strangulation can present with variable symptoms. The clinical presentation was first described by Moritz Borchardt, who was a German surgeon in 1948, as upper abdominal pain, retching, and blockage against placement of a nasogastric tube. The classical Borchardt’s triad in acute gastric volvulus is (1) minimal abdominal findings when the stomach is in the thorax, (2) a gas-filled viscus in the lower chest or upper abdomen shown by chest radiography, and (3) obstruction at the site of volvulus shown by emergency upper gastrointestinal series [31]. Symptoms can include retrosternal chest pain, epigastric pain, nausea, increased salivation with inability to swallow it, and retching with or without vomiting. If the stomach has incarcerated or volvulized, mucosal ischemia can lead to perforation and the patient may present in septic shock. The initial set of vital signs, a standard set of laboratories, and an upright chest X-ray are the appropriate first step to evaluate patient’s acuity. An ECG and troponin level should eliminate concerns for a cardiac event.

A significant paraesophageal hernia is often recognized on chest X-ray as a gastric bubble within the thorax. The X-ray or CT scan can also be helpful to determine perforation into the thorax by looking for a unilateral pleural effusion, typically on the left. It can also demonstrate intra-peritoneal perforation with free air under the diaphragm or CT scan (Fig. 8.2). If imaging demonstrates perforation, resuscitation and operative intervention should proceed without delay.

Fig. 8.2

Flouroscopic series with gastric volvulous. Source Jeyarajah and Harford [47, Fig. 24-7B], with kind permission from Clincal Gate (clinicalgate.com)

If the patient is hemodynamically stable without evidence of perforation, a nasogastric tube should be placed to decompress the stomach [32]. During placement, determine how easily the tube passes into the stomach. Gentle pressure may allow the nasogastric tube to pass, even with a gastric volvulus. The tube should be placed on low wall suction, and the evacuated content should be evaluated for blood. Gastric decompression may allow the stomach to untwist, thus reducing the risk of strangulation and turning an emergent/urgent scenario into a semi-elective one. If one cannot pass an NGT manually, it is mandatory to go to the OR for endoscopic placement in an urgent fashion.

Indications for Operative Intervention

If the NGT aspirate is non-bloody, the patient should be admitted and observed. The surgeon should complete a thorough workup and prepare for a semi-elective operative repair when possible [33, 34].

In the clinical scenario above, the patient is symptomatic, tachycardic, and has a leukocytosis concerning for sepsis which should make one concerned for a potential gastric perforation. This patient should be quickly resuscitated in preparation for urgent exploration. Once in the operating room, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) should be performed first. Careful inspection of the esophagus, particularly the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, is critical. If there is evidence of necrosis, the EGD should be terminated and a laparotomy performed. However, if the esophageal mucosa is viable, gentle pneumatic pressure can be used to open up or untwist the GE junction. Once within the stomach, use caution not to over insufflate. Careful inspection of the mucosa should reveal mucosal ischemia if present. A NGT should remain in place.

Laparoscopic Approach

Initial inspection should quickly determine whether the case is going to stay laparoscopic. If no mucosal ischemia is present, a diagnostic laparoscopy with the assessment of gastric wall viability should follow. If the stomach is merely edematous, but not dead, reduce the stomach from the chest.

If there is no perforation or ischemia, one can proceed to definitive repair if there is minimal gastric edema. A laparoscopic paraesophageal repair has a low morbidity and mortality. This approach can offer the benefits of minimally invasive surgery in a group of patients that are often elderly and have multiple medical problems [35]. The majority of surgery occurs in the mediastinum, and laparoscopic port placement is critical. If ports are placed too inferior, there may be difficulty reaching the operative field.

The diaphragmatic defect is commonly on the left side of the esophageal opening in the diaphragm. If necessary, the defect can be widened directly lateral to avoid injury to the inferior phrenic vein. At this point, determine whether the patient is a candidate for definitive laparoscopic repair. Inspect the posterior stomach by making a window thru the gastrocolic ligament.

If your assessment remains that the stomach is edematous, but not ischemic, a staged laparoscopic procedure should be considered. One should terminate the surgery and resuscitate the patient. Return to the OR in a few days for definitive repair once the initial inflammation and edema has had time to resolve [36, 37]. This time period would allow for a more comprehensive evaluation of the esophagus and the patients comorbidities.

Not a Candidate for Repair

Occasionally, the patient may not be a surgical candidate for definitive repair of the diaphragm due to severe comorbidities. For the patient who has limited independence, chronic illness or is infirmed and would not tolerate a laparoscopic repair, an alternative would be a gastropexy with a laparoscopic or endoscopic gastrostomy tube. A laparoscopic approach is necessary to make sure the stomach is reduced and not volvulized. Either a laparoscopic gastrostomy tube or endoscopic approach can be used for gastric fixation to the anterior abdominal wall to prevent recurrence of a gastric volvulus. There are two options for gastric fixation: Two gastrostomy tubes can be placed or one gastrostomy tube and gastropexy of the falciform. The second fixation point should prevent recurrent herniation or volvulus [38].

Laparotomy

If there is mucosal ischemia demonstrated on EGD or evidence of ischemia or hemorrhagic fluid on laparoscopy suggesting gastric compromise, one should proceed to a laparotomy. An upper midline or chevron incision can be used to expose the upper abdomen. The surgeon should mobilize the left lobe of the liver to expose the esophageal hiatus and retract the liver to the right with a fixed retractor. Manual reduction of the stomach from the hernia with inferior retraction should proceed with caution. The diaphragmatic defect will commonly require widening laterally to allow for safe gentile reduction of the stomach. Commonly, there may be adhesions preventing complete reduction that can be taken sharply taking care to avoid entering the mediastinum or thoracic space.

At this point, the essential decision is to address either the stomach or the paraesophageal hernia. If there is perforation, ischemia, or any degree of gastric compromise, the procedure becomes primarily a gastric resection. If the stomach is healthy and completely viable, one can proceed to repair the paraesophageal hernia.

In the setting of gastric perforation, the mediastinum and the upper abdomen are contaminated. These patients are commonly in septic shock and may be hemodynamically unstable. At this point, the surgeon must make the decision to proceed with a “damage control surgery.” The stomach is mobilized out of the chest. Typically, the greater omentum requires mobilization off the stomach. The goal would be to leave as much viable upper stomach for future reconstruction. The distal line of resection should be beyond the pylorus. A NGT is left in the gastric remnant, and the upper abdomen briskly irrigated. A temporary abdominal closure is placed.

The patient should be transferred to ICU for continued resuscitation and broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage. Once resuscitated, the patient can return to the operating room for definitive enteric reconstruction and diaphragmatic repair. Re-exploration should occur promptly as soon as the patient has been appropriately resuscitated. In the setting of a contaminated surgical field, the tissue will commonly be edematous during the re-operation for reconstruction. This will result in a more friable and edematous operative field.

Reconstruction

Paraesophageal hernias are a real hernia with a true hernia sac including the peritoneal layer [39]. Whether you are doing a reconstruction of the stomach or just a paraesophageal hernia repair, the hernia sac must be dissected free and completely remove from the mediastinum cavity. Care must be taken to avoid entering the thoracic pleura. Gross contamination from gastric perforation or ischemia increases concern for postoperative mediastinitis or empyema. If a hemi-thorax has been violated, it is mandatory to briskly irrigate it and place a thoracostomy tube for drainage.

The stomach should be reconstructed first. The esophageal hiatus should be determined to be below the diaphragm. It may be necessary to free the esophagus from the mediastinum to bring it down into the abdomen. This will be important during the paraesophageal repair. If sufficient amount of gastric pouch is viable, the reconstruction can be completed utilizing a Roux-en-Y reconstruction in standard fashion. A side-to-side gastroenteric (Bilroth II) anastomosis is commonly not possible nor recommended, as it will not reach up near the esophageal hiatus. In the rare occasion where the majority of the stomach is infracted and resected, an esophageal enteric anastomosis will need to be reconstructed. In this setting, a Roux-n-Y reconstruction is recommended with or without a reverse J pouch.

Stomach Reconstruction

Paraesophageal Hernia Repair

There are limited indications for a gastric fundoplication in this setting as it can only be performed when no gastric resection has been done. Primarily, it would be to protect an injury to the esophagus during dissection. The type of fundoplication used is beyond the scope of this chapter. In this setting, primary repair of the diaphragmatic defect is adequate [41].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree