Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

Eugenia-Daniela Hord

Pain, whose unchecked and familiar speed Is howling, and keen shrieks day after day.

—Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1792–1822

In 1995, the International Association for the Study of Pain introduced the name Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS). Complex Regional Pain Syndrome I (CRPS I) and Complex Regional Pain Syndrome II (CRPS II) are new names for two classic neuropathic pain syndromes previously known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy and causalgia. The new terminology was suggested to avoid the misleading term “sympathetic,” and to create uniform diagnostic criteria. Although there are still some dissenters, the new terminology is now largely accepted. CRPS I occurs without a definable nerve lesion, whereas CRPS II follows an identifiable major nerve lesion. On the basis of the presence or absence of the sympathetic component of pain, both types of CRPS can be divided further into sympathetically maintained pain (SMP) and sympathetically independent pain (SIP). A diagnostic sympathetic blockade can help distinguish SMP from SIP. These syndromes remain among the most fascinating and enigmatic of the pain syndromes.

I. HISTORY

The clinical syndrome we refer to as CRPS was scarcely mentioned in the medical literature before 1864 when Weir Mitchell, an American Civil War physician, described a syndrome consisting of burning pain, hyperesthesia, and trophic changes following nerve injury in the limbs of the soldiers. He named this pain syndrome causalgia.

Similar pain states were later documented in postsurgical patients, as well as in those with no clearly inciting cause. In the 1920s, Leriche, a French surgeon, established a link between the sympathetic nervous system and causalgia by demonstrating that sympathetic blockade or sympathectomy relieved the symptoms

of many of his patients. Patients with no clear-cut peripheral nerve injury, or those with pain in more than one peripheral nerve distribution, had what became known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy, which is now called CRPS I.

of many of his patients. Patients with no clear-cut peripheral nerve injury, or those with pain in more than one peripheral nerve distribution, had what became known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy, which is now called CRPS I.

In 1946, Evans devised the term reflex sympathetic dystrophy to describe a similar syndrome in patients with no obvious nerve damage. Since then, numerous attempts have been made to explain the pathophysiology behind these clinical features, and a host of different names have been used to describe them.

II. BASIC MECHANISMS

Numerous theories have been offered to explain the pathophysiology of CRPS, but the exact mechanisms remain unclear. Most theories postulate that sympathetic dysfunction plays a significant role in the development and maintenance of the syndromes. Indeed, CRPS and SMP are closely integrated. However, there are CRPS syndromes in which part or all of the pain appears to be SIP.

CRPS most likely involves both peripheral and central mechanisms. Peripherally, one observes events after nerve injury that herald long-term changes in neural processing. In animal models, persistent afferent small-fiber activity begins days to weeks after peripheral nerve ligation or section, and can be measured at the site of a developing neuroma as well as in the dorsal root ganglia. The neural sprouts at these sites have growth cones, which have mechanical and chemical sensitivities not possessed by the original neurons. These neural sprouts also may have increased numbers of sodium channels, leading to increased ionic conductance and hence increased spontaneous activity. There is also evidence of an abnormal coupling between sympathetic efferent and nociceptive afferent neurons (C-fibers and/or afferent somata within the dorsal root ganglia). It is hypothesized that a partial nerve lesion induces an up-regulation of functional α2 adrenoceptors at the plasma membrane of nociceptive fibers. These mechanisms could be the pathologic pathway of SMP. Additionally, more recent evidence supports the involvement of neurogenic inflammation in the pathogenesis of edema, vasodilation, and sweating in CRPS.

Centrally, changes in the morphology of the spinal dorsal horn ipsilateral to a peripheral nerve injury may be secondary to intrinsic mechanisms arising in response to a chronic barrage of impulses, or in response to retrograde transport of chemical factors from the area of the lesion. The role of glutamate release in the spinal cord after peripheral nerve injury is being evaluated with growing interest. Increased spontaneous activity in the primary afferent neuron may be a factor leading to spinal cord glutamate release. The fact that some patients could have hemineglect further supports the involvement of the central nervous system in the pathogenesis of CRPS.

III. CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The initial signs and symptoms of CRPS may begin at the time of injury or may be delayed for weeks. Sometimes, the traumatic event cannot be identified. CRPS I occurs without a known nerve lesion, whereas CRPS II consists of the same signs and symptoms

following an identifiable major nerve lesion. Because CRPS I and II have identical symptoms, it seems likely that the cause of CRPS I is also nerve injury but that the nerve injuries go undetected because they are partial, fascicular, or involve primarily small unmyelinated axons. These specific types of nerve lesions are notoriously difficult to diagnose by examination or electrodiagnostic studies.

following an identifiable major nerve lesion. Because CRPS I and II have identical symptoms, it seems likely that the cause of CRPS I is also nerve injury but that the nerve injuries go undetected because they are partial, fascicular, or involve primarily small unmyelinated axons. These specific types of nerve lesions are notoriously difficult to diagnose by examination or electrodiagnostic studies.

CRPSs are characterized by pain, changes in cutaneous sensitivity, autonomic dysfunction, trophic changes, and motor dysfunction. Untreated CRPS was characterized by three stages: acute, dystrophic, and atrophic. However, the sequential progression is hard to identify now that most patients are treated and do not display the later stages of disease progression.

Spontaneous pain is present in the majority of the patients. It can be burning, sharp stabbing, electric shocklike aching, and the quality can vary in time. The pain appears disproportionate to the inciting event. Sensory changes are common CRPS and include allodynia and hyperalgesia. Sensory deficits also can be present.

Autonomic dysfunction manifests as edema, changes in sweating (hypo- or hyperhidrosis), skin color changes (red or pale), and skin temperature differences. These signs can vary from time to time, and may be reported despite not being obvious at the time of the examination.

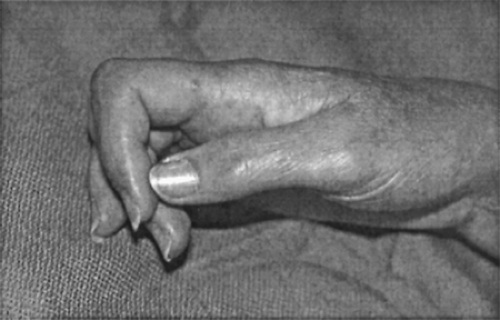

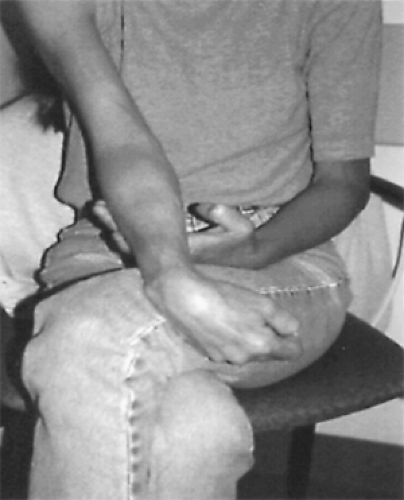

Trophic changes are largely the result of disuse. They include changes in nail growth and aspect, skin changes (can be thin and shiny or thick), hair loss, or hypetrichosis (see Fig. 1). Bones are osteoporotic and joints may ankylose (see Fig. 2).

The motor dysfunction includes weakness and later atrophy. Dystonia and tremor are also described.

IV. DIAGNOSIS

Pain is the cardinal feature of CRPS, but there are also sensory changes, autonomic dysfunction, trophic changes, motor impairment, and psychological changes. The diagnosis is based on the

whole clinical picture, with additional information from carefully performed and interpreted confirmatory tests to ascertain the presence or absence of SMP and autonomic dysfunction. These include diagnostic sympathetic blockade (e.g., stellate ganglion block, lumbar sympathetic block) and tests such as the quantitative pseudomotor axon reflex test, which allows a continuous hygrometric assessment of pseudomotor activity and is considered a good indicator of C-fiber function. Clinical experience suggests that early intervention, as well as early diagnosis, is helpful. Table 1 lists the common clinical features of CRPS used in the differential diagnosis of CRPS, and diagnostic criteria are listed in Table 2.

whole clinical picture, with additional information from carefully performed and interpreted confirmatory tests to ascertain the presence or absence of SMP and autonomic dysfunction. These include diagnostic sympathetic blockade (e.g., stellate ganglion block, lumbar sympathetic block) and tests such as the quantitative pseudomotor axon reflex test, which allows a continuous hygrometric assessment of pseudomotor activity and is considered a good indicator of C-fiber function. Clinical experience suggests that early intervention, as well as early diagnosis, is helpful. Table 1 lists the common clinical features of CRPS used in the differential diagnosis of CRPS, and diagnostic criteria are listed in Table 2.

Figure 2. Woman with severely affected right arm. Muscle wasting is pronounced and there are flexion contractures. |

Table 1. Common clinical features of CRPS | |

|---|---|

|

Table 2. IASP diagnostic criteria for CRPS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

The diagnosis of CRPS requires the exclusion of confounding medical problems, as well as the evaluation of diagnostic criteria. The IASP

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree