INTRODUCTION

Compartment syndrome occurs when increased pressure within a limited space compromises the circulation and function of the tissues within that space. It was first described in 1881 by Richard Van Volkmann, a German physician who noted that paralysis and contractures were the late sequelae of an interruption of the blood supply to the muscles in the forearm. In 1924, it was shown that the result could be prevented by prompt surgical decompression of the compartment.

Today, a high degree of clinical suspicion, coupled with timely surgery, can be used to save function of the muscles and nerves that are at risk of permanent damage from elevated compartment pressures.

ANATOMY

The borders of a confined space are often made up of bone or tissue that offers minimal capacity to stretch. Any increase in volume within that compartment results in an elevated intracompartmental pressure. In the lower extremity, the most common site is at the level of the tibia and fibula, where 40% of compartment syndromes occur. The lower leg has four compartments: anterior, lateral, superficial posterior, and deep posterior (Figure 278-1). (Also see Figure 271-1 in chapter 275, Leg Injuries.)

The upper leg has three compartments: anterior, posterior, and medial. Due to the larger size of these compartments and their interconnectivity, they are less predisposed to elevated tissue pressures. The foot and buttock region of the leg also have a lower incidence of compartment syndrome.

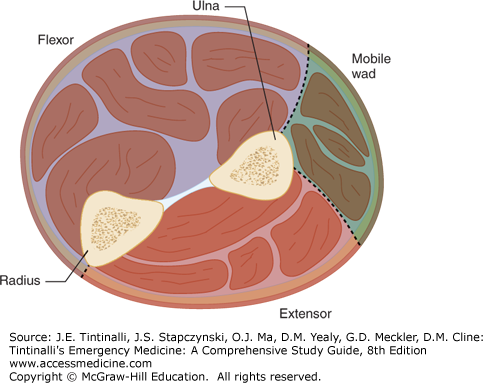

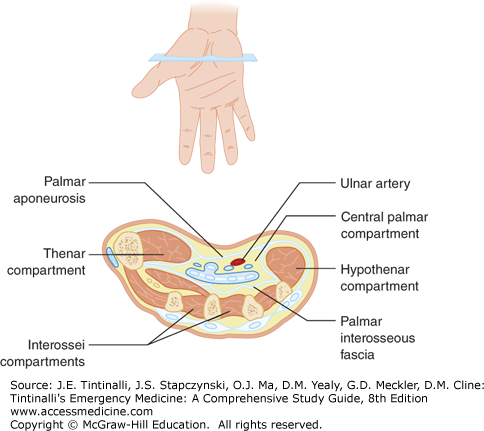

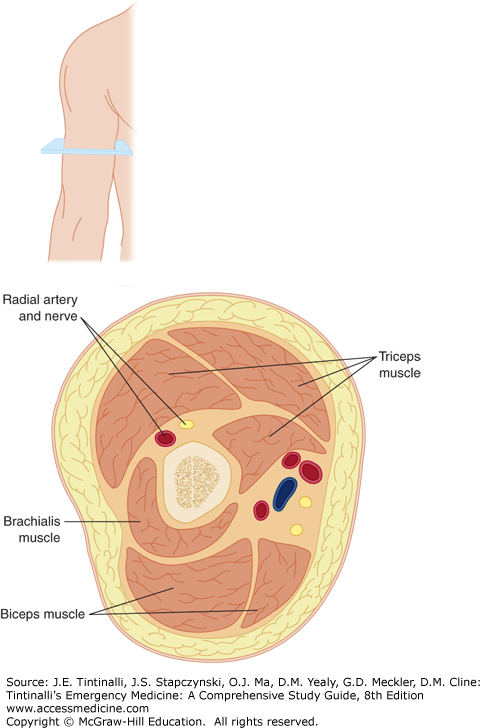

In the upper extremity, the forearm has three compartments: flexor, extensor, and mobile wad (Figures 278-2 and 278-3). These are the high- risk areas in the arm. The hand (Figure 278-4) or upper arm (Figure 278-5) is less likely to develop a compartment syndrome.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Muscle death and nerve damage in the setting of compartment syndrome are caused by prolonged elevation of tissue pressures. This can result from external forces, such as a cast or tight dressing, which compress a compartment. It can also result from an increase in the volume of a compartment that exceeds the limits of the surrounding fascia’s ability to stretch. This may be the result of hemorrhage into a compartment or edema caused by reperfusion injury (Table 278-1). In effect, any mechanism that increases the volume of blood or tissue within the compartment has the potential to cause a compartment syndrome. Tissue perfusion is determined by the difference between the arterial blood pressure and the pressure of the venous return. As tissue pressure increases within a compartment, the normal gradient between arterial and venous pressure decreases.

| Orthopedic | Tibial fractures Forearm fractures |