Home care

Ninety percent of the final year of life is spent at home, no matter where the patient eventually dies. Home is a special place, a state of mind, a place to be ourselves most fully. It represents life, activity, self determination, and retaining control, rather than illness, passivity, and the “patient mode” of inpatient care. The preferred place of care may seem to change nearer death; this may be by default—for example, when patients or their carers feel unable to cope, for relief of symptoms, the fear of being a burden, and sometimes conflict between the patient and the carer’s choice. But it has to be questioned whether this is real “choice” or a response to practicalities by default—with better planning and support can a change sometimes be averted? Many people would choose to spend most time at home but to die in a hospice, an appropriate choice for many—yet many of our hospice services would struggle currently to meet this preference, especially for patients without cancer.

- 90% of the final year of life is spent at home

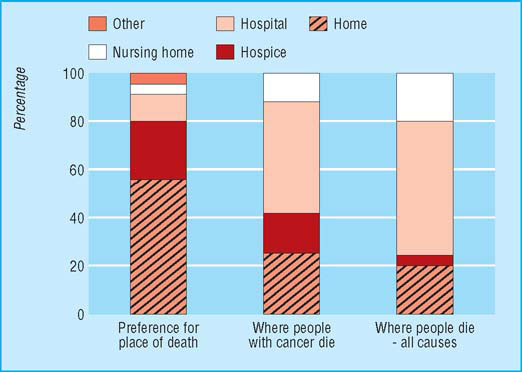

- Most people prefer to die at home, but the number who choose a hospice is increasing

- The home death rate is low (23% for patients with cancer, 19% for all deaths)

- The hospital death rate is high (55% for patients with cancer, 66% of all deaths)

- 21% of those aged over 65 years in care homes (nursing and residential homes)

- Death in hospital is more likely if patients are poor, elderly, have no carers, are female, or have a long illness

- Each GP has about 30–40 patients with cancer at one time

- District nurses coordinate most palliative care in the home

- Primary palliative care is optimised by formalised specialist support

- Less support is available for patients with illnesses other than cancer and their carers and GPs

- Gaps in community care include control of symptoms, support of carers, 24 hour nursing care, night sitters, access to equipment, out of hours support

- Improving community palliative care services (including care homes) has an impact on hospitals and hospices

- The average length of stay in a hospice is now two weeks, 98% of patients have cancer and 50% of patients in hospices will be discharged

- Enabling patients to die in the place of their choice can have a positive effect on the family’s bereavement

Priorities for end of life care in England, Wales, and Scotland (data from Cecily Saunders Foundation and National Council for Palliative Care)

With the increase in advanced directives or living wills, it is more important than ever to have these difficult discussions with patients and their families early on and together form an advanced care plan including decisions about their preferences, such as place of care, which should be noted and communicated to others. Other areas to cover include a nominated proxy, do not resuscitate (DNR) decisions, what patients would or would not like to happen, what to do in a crisis, and special requests—for example, organ donation. This enables a greater sense of self determination and control and better planning of care based on the needs of the patient.

Time is short for the dying. Towards the end of life the pace of change may be rapid, and without good planning and proactive management, the speed of events can catch out the best of us. Enabling dying patients to remain at home involves a close collaboration of many people, services, and agencies, both generalist and specialist and, at best, an agreed system or managed plan of care (such as the gold standards framework). A bewildering number of people can become involved, sometimes causing a confusing mismatch of services and adding to the trauma of the dying process. Patients and carers appreciate the continuity, coordination, and ongoing relationship with their primary care team or specialist provider.

So within community palliative care there is a pressing need for active anticipatory management, coordination, and “orchestration” of services to enable good home care for the dying. Although GPs may feel pressurised by time constraints, the primary care team, particularly the district nurses, are in a key role to perform this function, and often they are the mainstay of care at this most crucial time. This is in line with the “cradle to grave” concepts inherent in primary care; knowledge of context and community and of continuing supportive relationship and care of the dying is close to the heart of most people working in primary care. As Gomas (1993) said “Palliative care at home embraces what is most noble in medicine: sometimes curing, always relieving, supporting right to the end.”

The needs of dying patients

Palliative care services should respond to the needs of patients and carers and deliver to their agenda. This requires a holistic assessment, including non-medical psychosocial issues. In general, patients want to remain as free from symptoms as possible and to feel secure and supported, with good information and proactive planning. This allows the continued journeying to other important and deeper levels involved in the dying process—for example, loving relationships, retaining dignity, self worth, spiritual peace. Various studies confirm what is required of healthcare professionals by dying patients and their carers. Good communication and information figure largely—for example, clear advice on what to do in an emergency, what to expect—and also the steadfast continuity of relationships, the “being there,” as “companions on the journey” with our patients. This trusted relationship and supportive role should never be underestimated.

Support from councillors or psychologists is sometimes available, which may smooth the transition and mental adaptation required in coming to terms with dying. Social services need to be involved for advice on financial benefits, continuing care services, respite, and social care. The DS1500 attendance allowance form should be used by primary care teams to enable speedy additional funding for those in the last six months of life. Spiritual needs may be hard to assess and personally challenging but vital to enable people to move towards a peaceful conclusion of their lives. Referral to the appropriate spiritual advisor and awareness of ethnic differences in this diverse multicultural nation is all part of good care. Practical needs include equipment such as mattresses, wheelchairs, commodes, syringe driver, and home modifications such as external key boxes and handrails, etc.

- Nursing and medical care

- Good symptom control

- Information—for example, what to expect/who to phone in a crisis

- Practical advice/help/equipment

- Good liaison across boundaries

- Continuity of relationship with clinicians

- Social care—for example, continuous care funding, etc

- Support for carers—night sitters, Marie Curie nurses, etc

- Carers’ needs assessed

- Preparing families for a death

- Information on what to do after death

- Continuity of relationship

- Being listened to

- Opportunity to ventilate feelings

- Being accessible

- Effective symptom control

Use of the gold standards framework, NICE Guidance on Supportive and Palliative Care, Generalist Palliative Care www.nice.org.uk

- Patients with needs for palliative care are identified according to agreed criteria and a management plan discussed within the multidisciplinary team

- These patients and their carers are regularly assessed with agreed assessment tools

- Anticipated needs are noted, planned for, and addressed

- Needs of patients and carers are communicated within the team and to specialist colleagues, as appropriate

- Preferred place of care and place of death are discussed and noted, and measures taken to comply when possible

- A named person in the practice team orchestrates coordination of care

- Relevant information is passed to those providing care out of hours, and drugs that may be needed left in the home

- A protocol for care in the dying phase is followed, such as the Liverpool care pathway for the dying patient

- Carers are educated, enabled, and supported, which includes the provision of specific information, financial advice, and bereavement care

- Audit, reflective practice, development of practice protocols, and targeted learning are encouraged as part of personal, practice, and primary care organisation/NHS trust development plans

Primary care team response

Working as a team, the PHCT can provide continuous and coordinated supportive care in the community. Early referral to the district nursing service is preferred, allowing time for a full assessment of the needs of the patient and carer, early referral to other services, ordering of equipment, and time to develop a relationship with the patient and carer as advocate and “key worker”’ before later deterioration.

Out of hours care

Particular attention should be paid to improving the continuity of care out of hours, which accounts for about 75% of the week. Without this vital aspect, all the good work of primary care can be instantly dismantled, and the patient can be admitted to hospital in crisis, possibly to remain there until death. In the UK, changes in the contracted out of hours cover might threaten the continuity of care for dying patients. With better proactive management and the use of an agreed protocol, a handover form, and good access to drugs, however, these situations could be avoided.

Support for family and carers

Support for the family and carer can be one of the most important aspects of the holistic care provided by primary care teams, backed up by hospice support if available. Carer breakdown is often the key factor in prompting institutionalised care for dying patients. Carers should be included as full members of the team, enabled, forewarned, informed, and taught to care for the dying patient to the level desired. This has consequences for the carer in bereavement, with a greater satisfaction that the patient’s final wishes were fulfilled and fewer “if only…” regrets later. The toll of caring for a dying person can be considerable in both physical and emotional terms; many carers are elderly and infirm themselves and there is an increased morbidity and mortality of carers in bereavement.

In some surveys of both patients and families, the carer’s anxiety is rated alongside the patient’s symptoms as the most severe problem. There is resounding evidence that without support from family and friends it would be impossible for many patients to remain at home.

This is one issue where evidence confirms that primary care can make a real and valued difference. Many carers, however, feel that GPs do not understand their needs, and in turn many GPs and district nurses feel they lack the relevant time, resources, and training to take a more proactive role. The primary care team, however, is in a key position to help, both personally and in coordinating services. Separate assessment and practical support for carers is therefore required and, with support from social services and self help groups, carers are then more likely to be able to withstand the pressure. Those without carers may struggle even more, and they present particular difficulties for primary care in an age of increasing solitary living.

Carers need time to ask questions, to discuss decisions, to help relieve their anxiety, and to create a better understanding of what is happening. It is often helpful to rehearse with the carer what to do in certain situations, such as if the patient has uncontrolled symptoms or when the patient dies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree