Community-Based Primary Care Resources for Children

Stephen Paul Holzemer PhD, RN

Maria Scaramuzzino MSN, RN, PNP

Jane Kiernan PhD, RN

INTRODUCTION

This chapter provides a context for understanding the interconnectedness of children and families with the communities in which they live. Caring for children effectively, using appropriate resources is a global concern (Zotti, 1999; Morabia, 2000). This context underpins suggested community resources that pediatric primary care providers may want to use when working with children and their families. Additional community-based resources specific to the topic of discussion are found at the end of each remaining chapter in this text.

RESOURCE ALLOCATION: FEAST OR FAMINE?

Communities at the national, regional, and local levels make health-related resources available for treating illness and keeping people healthy. Many variables influence how resources are allocated. Primary care providers can influence some variables but cannot control others. For example, they cannot control the outbreak of a new pathogen, but they can modify and influence the public’s response to a resulting epidemic. Providing community-based primary care resources to meet the needs of children and adolescents is particularly challenging because these age groups represent a vulnerable population. Factors contributing to this vulnerability and ways for providers to deal with them are discussed below.

Children’s Health Issues May Be Ignored Until a Crisis

One major influence on resource allocation for health care involves the fact that many resources become allocated only in response to crisis, when groups initially affected by the situation in question demand action. For example, early in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) pandemic, clinicians and people living with AIDS greatly increased the number and types of resources available to fight this disease. As more women, people of color, and children contract AIDS, funding for treatment and research may decrease if these aggregates cannot advocate successfully for what they need. Furthermore, when another major public health crisis occurs, it inevitably will trigger the restructuring of resource allocation, leaving people with AIDS in danger of losing needed resources.

Preventive Care for Children Is Undervalued

Another concern in resource allocation relates to how people value services. Many communities tend to develop more resources for illness care than for disease prevention or rehabilitation. Large medical centers devoted to cardiovascular, neoplastic, and other physical and psychological problems exist to cure illness, not to prevent it. The cost of illness care cripples efforts to move the concept of prevention beyond the philosophical to the real. This concern is especially important for the pediatric population, because much of pediatric primary care is directed toward health promotion and disease-prevention strategies.

Children Rely on Adults for Needed Resources

The needs of children and adolescents range from predictable and less common illnesses to complex physical, emotional, and social crises (Belcher, & Shinitzky, 1998; Britto et al., 1999; Xiaoming, Stanton, & Feigelman, 1999). Regardless of their individual concerns, all children and adolescents must rely on adults for needed resources; rarely are they able to negotiate for health resources themselves. Conflicts arise because many adults who identify and secure the needs of pediatric populations have no expertise in the care of children and adolescents. The scandal of lead poisoning provides an example in which children and adolescents were exposed to danger and not cared for properly by individual adults or society (Markowitz & Rosner, 2000). Because of the political power of the paint industry, children were and in some places continue to be exposed to lead paint.

Providers must exert serious efforts to guarantee sufficient resources for preventing illness while also treating and rehabilitating sick children and adolescents. Both traditional and complementary perspectives can play a part in this process (Ferris et al., 1998; Sikand & Laken, 1998). A master plan for meeting the needs of children and adolescents should be a primary goal for every well-functioning community. Politicians and others who make decisions about resource allocation may need guidance in meeting the needs of this special aggregate. Models of community assessment are useful in setting up a structure in which communities can allocate and distribute their resources and evaluate their benefits.

Children Are Unable to Negotiate for Resources

An increasing concern is the influence of special interest groups in shaping what services are available to the public. The reality is that resources are not available to provide all people with all health care needs. The traditionally silent voices of vulnerable groups (eg, children, mentally ill, homeless) are little match against the powerful voices of special interest lobbies, who strive to meet their own needs and achieve their own ends, sometimes at the expense of others.

These “others” obviously include vulnerable aggregates. For example, the politics of reproductive health and a woman’s control over her body significantly influence the care that young women will receive. Some influential conservative political and religious groups want to limit access to some areas of women’s health care (eg, genetic testing, in-vitro fertilization) for adolescents. If they succeed, emancipated minors may have difficulty negotiating for health care services if they do not have a system of adults who support their choices.

These “others” obviously include vulnerable aggregates. For example, the politics of reproductive health and a woman’s control over her body significantly influence the care that young women will receive. Some influential conservative political and religious groups want to limit access to some areas of women’s health care (eg, genetic testing, in-vitro fertilization) for adolescents. If they succeed, emancipated minors may have difficulty negotiating for health care services if they do not have a system of adults who support their choices.

Contemporary decentralization of funding resources may be problematic. Some block grants, for example, while supporting the autonomy of communities to endorse programs they desire, do not provide for the checks and balances that protect groups who cannot negotiate for resources. If children and adolescents do not receive needed services, their health can be affected negatively as they move into adulthood. Failure to learn about or receive primary prevention measures related to health promotion and specific protection may result in serious acute and chronic illness in the future.

COMMUNITY-BASED PLANNING FOR COMPREHENSIVE SERVICES

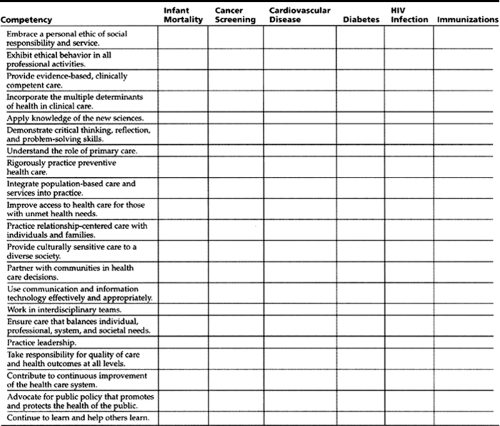

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1998) has developed an initiative to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health by the year 2010. Foci of this project include infant mortality, cancer screening and management, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and child and adult immunizations. Healthy People 2010, created through public comment, attempts to move the public away from a preference for illness care toward designing appropriate preventive measures for comprehensive health care. The intention of this national prevention plan is to empower diverse populations to work together to improve health. One analogy compares this plan to a road map used by different lay and professional individuals, families, groups, and aggregates who are all working together to maintain health. Recipients and providers of care have developed the Pew Commission Competencies (Bellack & O’Neil, 2000),

which are requirements for successful primary care providers in the 21st century. Together, Healthy People 2010 and the Pew Commission Competencies provide a template for identifying where community-based services for children exist and where they still need to be developed.

which are requirements for successful primary care providers in the 21st century. Together, Healthy People 2010 and the Pew Commission Competencies provide a template for identifying where community-based services for children exist and where they still need to be developed.

In planning comprehensive health care for children and adolescents, providers can combine the preventive strategies of Healthy People 2010 with the expected health care provider competencies of the Pew Commission. For example, a provider who is considering the competency “improve access to health care for those with unmet health needs” might be inspired to partner with a local business to address diabetes management. The business might seek out the support of a recognized performer or athlete to conduct or sponsor a series of programs to children at different age levels about eating habits. For the competency of “continue to learn and help others learn” combined with the health concern “immunizations,” the clinician could bring together students from schools of health professions to establish a phone bank to help parents keep appointments for vaccinations. Table 3-1 is a worksheet to help primary care providers, families, and community representatives identify areas where services need development or continued support.

Alliance for Health Model

The Alliance for Health model is one blueprint that provides a broad outline to evaluate needs in various aggregates (Holzemer & Arnold, 1998; Holzemer, Singleton, & Green-Hernandez, 1999). The five major components of the Alliance for Health model are as follows:

Community-based needs

Care management techniques

Influences on resource allocation decisions

Validation of services by the client

Expertise of the interdisciplinary team

Display 3-1 identifies subcategories for assessment of the first three components. Patterns of morbidity and mortality are, for example, critical components of community-based needs. Knowing the patterns of disease, illness, and death are central to understanding the needs of the community. Similarly, the mix of patient problems is essential to understanding systems of case management. Finally, a population’s values and beliefs will directly influence decisions about resource allocation. These first three components of the model rely on the last components for practical application. Validation of services by the client and, when necessary, a parent or guardian increases the probability that a treatment plan will succeed. Validation of services means that the patient and family find services acceptable, affordable, and culturally appropriate. The expertise of the interdisciplinary team directly influences how accurately and efficiently the patient–provider team works. This expertise is defined as the skill and success various disciplines have in working together with clients to solve health-related problems.

DISPLAY 3–1 • Community-Based Needs, Care Management Techniques, and Influences on Resource Allocation Decisions

Community-Based Needs

Patterns of morbidity and mortality

Demographics (age, gender, education level, income, housing)

Environmental concerns

Public services (fire, police, sanitation, education, recreation, and sports)

Aesthetics (art, music, culture, religion)

Health-related facilities (hospitals, community-based organizations, subacute and custodial care facilities, public health facilities, home care organizations)

Care Management Techniques

Mix of patient problems

Public’s expectations for care

Competence of professionals

Accepted standards of care

Use of interdisciplinary care plans or action plans

Influences on Resource Allocation Decisions

Patterns of resource allocation

Population’s values and beliefs

Reliance on local, regional, and federal government funding

Influence of special interest groups

Patterns of insurance coverage

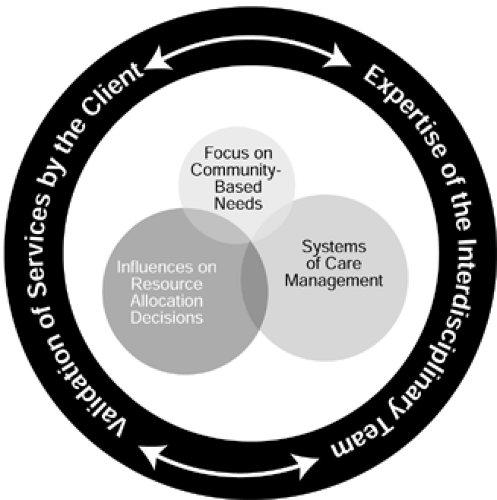

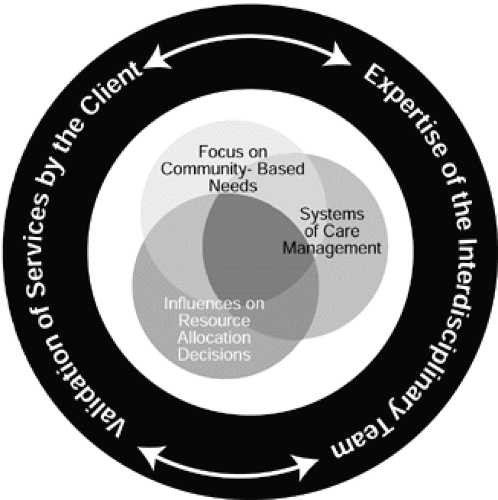

For visual effect, Figure 3-1 and Figure 3-2 show interlocking circles that represent community-based needs, care management techniques, and influences on resource allocation. Careful assessment of these components is necessary to provide comprehensive health care. Figure 3-1 shows a well-integrated community as determined by the Alliance for Health model. Figure 3-2 shows a less integrated model, which could represent a situation where an influx of children into a community has occurred, and their specific health needs are not well known. In such a situation (eg, high emigration or a natural disaster that caused displacement of people), specific community-based needs will need to be assessed. The existence of systems of care management and

methods for appropriate resource allocation are limited until needs are assessed adequately.

methods for appropriate resource allocation are limited until needs are assessed adequately.

Figure 3-1 The Alliance for Health model for community health assessment and care delivery in community-based pediatric care. |

Combined Adult and Pediatric Services

Physically separating care of children and adolescents from care of adults will likely decrease the access to needed services. Limited money and time make double visits to care providers impractical for families. Such limitations are special concerns because integration and accessibility are two cornerstones of primary health care (Donaldson, Yordy, Lohr, & Vanselow, 1996). Some institutions have addressed the need for facility fiscal management by restricting the hours and location of primary care delivery, which may make securing services for adolescents and children problematic.

Combining the care of children and adolescents with that of adults who care for them is philosophically sound but not without difficulties. Challenges in combining services include finding times when the schedules of providers and patients mesh closely. In many situations, services need to be accessible when both caregiver and child are available. When services are combined, facilities may need to provide child care and supervision when adult caregivers need privacy (eg, during physical examinations or counseling). In some facilities, decentralization of support services like blood work and roentgen (x-ray) evaluations demands time away from work or school for the child and caregiver.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree