Why is good communication necessary?

Effective communication is essential in all clinical care. In palliative care, professionals need good communication skills to be aware of the patient’s unspoken concerns. They also need to exchange information between members of the multidisciplinary team. Patients and their carers consistently identify a need for good communication with professionals, poor communication being the most common reason for complaints about doctors.

Why is communication difficult?

If communication between healthcare professionals and patients is to be improved, the reasons why communication in palliative care may be difficult must be understood.

Death remains a taboo subject and nowadays is unfamiliar to the public as most people die in hospital. Patients may have many concerns; it may not be simply the prospect of premature death but the likelihood of an undignified painful process of dying that is frightening. Doctors may feel a sense of failure as there is a tendency to blame the bearer of the bad news. Furthermore, some professionals feel unprepared to deal with the patient’s emotional reactions or to admit to uncertainty.

Challenges in communication

The time of diagnosis, treatment, and recurrence of disease may be associated with considerable social and psychological morbidity, much of which remains unrecognised by healthcare professionals. It is not surprising that collusion and conspiracies of silence can develop when everyone is trying to protect the patient.

Barriers to good communication

An understanding of the factors that prevent good communication may lead to initiatives to improve it.

Lack of time

Lack of time is commonly used as a justification for inadequate communication as most clinicians have to work with unrealistic caseloads. Patients value extra time spent with them and can become more involved in decision making. Spending more time may be more efficient because it takes longer to resolve misunderstandings than to avoid them in the first instance.

Lack of privacy

Maintaining confidentiality is one way of respecting a person’s autonomy and forms an essential part of a trusting relationship. In practice absolute confidentiality is hard to achieve and breaches occur in hospital and community settings.

The presence or absence of relatives can create problems of confidentiality; professionals should not assume that the patient wants the relatives to be informed. If information is judged to be highly sensitive, the patient’s permission should be sought to share information with members of the multidisciplinary team on a “need to know basis.”

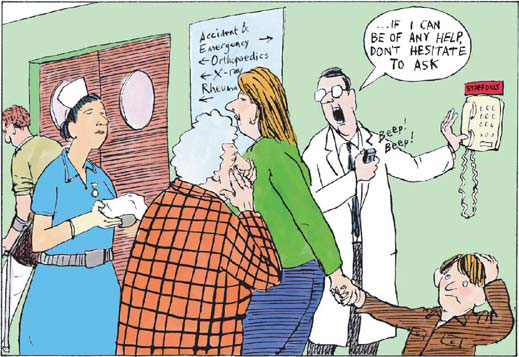

Good communication between doctor and patient is vital (photos.com)

- Provide patients with information about their diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment choices to plan realistically for the future

- Make patients aware of the services that might be available for them and their carers

- Clarify the patient’s priorities

- Enable a trusting relationship between the healthcare professional, patient, and family

- Reduce uncertainty and prevent unrealistic expectations while maintaining realistic hope

- Achieve informed consent

- Resolve ethical dilemmas

- Promote effective multidisciplinary teamwork

- Will the cancer come back? Fear of recurrence

- How long have I got? Fear for the future

- Why me? The search for meaning

- Am I still lovable? Body image and sexual concerns

- What can I do? Fear of loss of control

- Why won’t they talk to me? Need for honesty

- Will I be a burden to others? Fear of becoming dependent

- Where is the doctor? Need for medical support

Uncertainty

Communication is particularly difficult for patients, relatives, and professionals at a time of uncertainty. Patients need to have a sense of control over their life plans. Restoring a sense of control may enable patients to feel “safe” even in a life threatening situation. Doctors should feel able to acknowledge uncertainty, be prepared to discuss patients’ fears of death and dying, and assist them in setting goals for a limited future.

Embarrassment

A general reluctance in society to discuss death and dying combined with a desire not to cause patients further distress makes communication difficult. Listening is a key skill. The professional needs to convey to the patient that he or she is approachable and empathises with their suffering. Patients do not expect professionals to have answers to existential questions but they do need to have contact with another human being who is prepared to be with them and to listen to their fears.

Collusion

Collusion may arise when relatives feel that the patient would not be able to cope with bad news. This form of paternalism, which may spring from good motives, ultimately threatens patients’ autonomy. It is a serious breach of confidentiality to discuss details of a case with relatives before the patient has had an opportunity to absorb the information. If collusion exists then time is needed for the healthcare professional to explore the relative’s motives and feelings in a supportive way. Relatives also need to know that often the patient is fully aware of the gravity of the situation and is trying to protect them.

Maintaining hope

When patients become upset on hearing that their disease is no longer curable, their distress should be acknowledged. Given time, the patient can be encouraged to set goals other than cure—for example, relief of pain. Here healthcare professionals need to be alert for signs of clinical depression.

Anger

The doctor needs to listen to the patient’s story, eliciting all their concerns. Anger should be acknowledged and not dismissed as a part of a coping process. It is therapeutic for the patient to be allowed to vent their anger without interruption. Professionals should feel free to empathise and to express feelings of regret without necessarily accepting blame.

Denial

Initially, it is common for a patient to deny the bad news and this should be expected because it is an effective coping strategy. In dealing with persisting denial, it is important to give patients an opportunity to talk as they may wish further information at a later stage. Although most patients do want to be fully informed, it is important to respect the view of the small minority who don’t want further information about their diagnosis or prognosis. Patients in denial are frightened; they need patience and sensitive communication.

Not in front of the children

Children often demand information in a direct way. Older children have the same information needs as adults but require it in a form that is easily understood. Young children may need to assimilate information through the use of play, painting, videos, and books. Children need to tell their story and healthcare professionals have to be imaginative and uninhibited in helping them to articulate their distress. The natural feelings of protection should not generate situations of collusion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree