Common Orthopedic Complaints

Keith P. Mankin MD

Jennifer Griswold RN, MSN, PNP

INTRODUCTION: THE LIMPING CHILD

The presentation of a limp in the growing child is a frequent cause of concern. Although most limps are benign and transient, causes of limps range from minor trauma to serious illness.

• Clinical Pearl

Clinicians must take any limp seriously, since children complain of pain frequently but limp only in the context of true organicity.

An understanding of the entities that can cause a limp may help the provider to determine the severity and prognosis, as well as to assist the parents in dealing with the child’s problem. As with all medical problems, a careful and complete history and physical exam is essential. Radiographs are frequently recommended, since the likelihood of underlying pathology is higher in children than in adults. More specialized studies such as Technetium Bone Scan or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) may add information but are costly and may require sedation or anesthesia. Routine screening bloodwork (eg, complete blood count [CBC], cell differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]) is often useful to help rule out underlying infection.

The differential for a limping child should include the following:

Acute fracture

Septic joint, bone infection, or toxic synovitis (“irritable hip syndrome”)

Acute apophysitis (Osgood-Schlatter disease or Sever’s disease) and other “growing pains”

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE)

Acute back disorder (spondylolysis, infection, tumor, or disk)

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease (LCPD) (osteonecrosis of the hip)

Rheumatoid or other arthritides, including Lyme disease in endemic areas

Other bone or systemic pathology (primary tumors, leukemia, lymphoma, etc.)

Providers may suspect acute injury based on history and plain radiographs (see Chapter 43). The limb requires stabilization (brace or splint), and the clinician should refer the child to an orthopedic specialist as soon as possible for definitive care.

SEPTIC JOINT, OSTEOMYELITIS, AND TOXIC SYNOVITIS

Musculoskeletal infection is very common in younger children, and providers should always suspect it in the face of an acute gait disturbance.

• Clinical Pearl

A septic joint (septic arthritis) is a true surgical emergency that providers need to rule out first and foremost in any child with a limp.

Osteomyelitis or infection of the bone may have a more indolent presentation, but it is frequently associated with severe systemic signs and symptoms and requires aggressive treatment.

• Clinical Pearl

Benign transient or toxic synovitis is the most common cause of hip pain that clinicians treat. It is a diagnosis of exclusion, however, and the clinician should only consider it when he or she has comfortably ruled out the much less common but more dangerous conditions of septic arthritis and osteomyelitis.

Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology

In growing children, increased circulation to the joint and the growing ends of the bone facilitates seeding of these areas with bacteria. Thus, most cases of osteomyelitis and septic joint are from hematogenous spread. Direct penetration of the joint or bone also may lead to infection. Finally, contiguous spread of infection from the bone to the joint has been documented, so providers should consider concomitant orthopedic infections in all cases. Children with blood disorders or other chronic constitutional illnesses will have a higher incidence of infection with more atypical bacteria.

Toxic synovitis probably represents a response by the joint mounted against a non-specific irritant such as blood-borne virus. The joint produces an abundance of fluid (effusion) and may show signs of inflammation (eg, pain, swelling, erythema), which may mimic acute infection. The fluid, however, is sterile. Aspiration of the fluid may be delayed if the examination is relatively benign (ie, no systemic toxicity, minimal pain on joint range of motion) and the child can be closely observed over a short period (from 4 to 6 days) for worsening symptoms.

Epidemiology

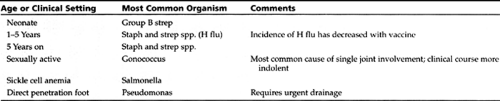

Orthopedic infections demonstrate a bimodal incidence, with peak occurrence in the young and the very old or immunocompromised patients. The most frequently involved skeletal areas are those of most rapid growth: knee, elbow, hip, and heel. Slower growing bones such as the clavicle, scapula, and spine are less frequently involved (Dagan, 1993). The most frequent infective agent varies somewhat by age and clinical setting (see Table 44-1).

Toxic synovitis tends to occur in young boys between ages 3 and 6 years and usually in association with or closely following a viral infection. This self-limited illness tends to resolve completely without sequelae in 1 week. The etiology of this very common condition remains unknown.

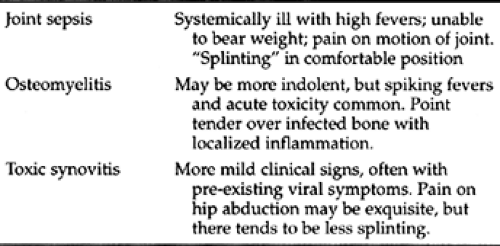

Diagnostic Criteria

Infection

The diagnosis requires positive blood or regional cultures. Up to 40% of joint aspirates in clinically septic joints, however, may be culture-negative (Dagan, 1993).

Toxic Synovitis

A diagnosis toxic synovitis is established by excluding infection and observing the typical clinical course of gradual improvement over several days.

Diagnostic Studies

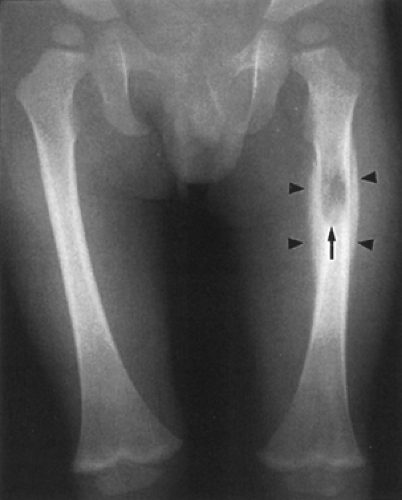

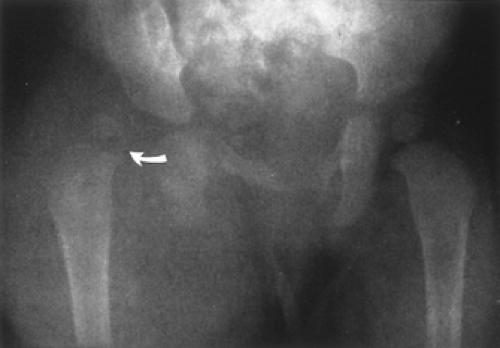

In joint infection, radiographs may show effusion and in extreme cases, subluxation of a joint. The reader is referred to Figure 44-1. In neonates, apparent joint disruption may be the only clue to a septic arthritis. Ultrasound may be useful to confirm fluid in the joint. For osteomyelitis, specific radiographic changes include periosteal reaction and bone destruction. Please see Figure 44-2 for osteomyelitis in a 2-year old child.

Figure 44-1 Dislocation of the hip from joint sepsis in a 6-month-old infant. (From Tolo, V.T., & Wood, B. [eds.]. [1993]. Pediatric Orthopedics in Primary Care. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.) |

• Clinical Pearl

Radiography findings may lag up to 4 weeks after the onset of clinical infection.

Technetium Bone Scan will be positive with 90+% sensitivity in osteomyelitis but may be less sensitive for a septic joint (Morrissey, 1996). Because of the association between septic arthritis and bone infection, a bone scan is recommended even when joint infection is proven on aspiration.

CBC and differential will show increased white blood cell counts in most infections of the bone and joint but will be normal in toxic synovitis. ESR is generally elevated for infection, but is non-specific. Both CBC and ESR may be falsely negative in very young children. C-Reactive Protein may be more specific for orthopedic infections (Unkila-Kallio, 1994), but it is costly and not readily available in all settings. In the toxic child, blood cultures are mandatory and may have a high yield of identifying the infective organism. Depending on the child’s age and clinical condition, the clinician may need to perform a complete septic work-up.

In the face of high clinical suspicion of joint infection, aspiration of the joint fluid is essential. The provider must culture the fluid, perform Gram staining, and test for white blood cells. A white blood cell (WBC) count greater than 100,000 is felt to be diagnostic for a true bacterial infection. A WBC count between 50,000 to 75,000 may indicate arthritis, sympathetic effusion from an osteomyelitis, or possibly a less virulent joint infection. Lowered lactic acid and glucose in the joint fluid (compared to serum levels) are also indicative of infection.

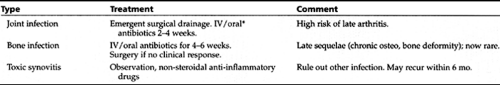

Management

The most important step in treatment is recognition of a potentially limb-threatening situation. Basic treatment strategies are described in Table 44-3. Since gram-positive organisms (staph and strep) predominate, currently recommended

antibiotic regimens are 2 weeks of intravenous (IV) treatment with 150 mg/kg/day of Oxacillin or Nafcillin divided every 6 hours, followed by 100 mg/kg/day of high-dose, oral Cephalexin divided every 6 hours for 4 weeks (Morrissey, 1996). Although quinolones such as ciprofloxacin may be more effective orally, these antibiotics are not used in children because of concern about growth arrest (Menschik, Neumuller, Steiner, et al., 1997). Joint arthritis is treated with 2 weeks of IV antibiotics alone. Clinicians should adjust all antibiotics according to cultures and sensitivities and response to treatment, as evidenced by symptom improvement and decreasing ESR. The treatment of toxic synovitis includes rest, reassurance, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and close daily follow-up, to ensure that the clinical course is one of gradual improvement.

antibiotic regimens are 2 weeks of intravenous (IV) treatment with 150 mg/kg/day of Oxacillin or Nafcillin divided every 6 hours, followed by 100 mg/kg/day of high-dose, oral Cephalexin divided every 6 hours for 4 weeks (Morrissey, 1996). Although quinolones such as ciprofloxacin may be more effective orally, these antibiotics are not used in children because of concern about growth arrest (Menschik, Neumuller, Steiner, et al., 1997). Joint arthritis is treated with 2 weeks of IV antibiotics alone. Clinicians should adjust all antibiotics according to cultures and sensitivities and response to treatment, as evidenced by symptom improvement and decreasing ESR. The treatment of toxic synovitis includes rest, reassurance, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and close daily follow-up, to ensure that the clinical course is one of gradual improvement.

• Clinical Pearl

Urgent or emergent referral is recommended for all children who have leg pain and any systemic toxicity. Clinicians may follow milder cases with less toxic presentations and normal lab work, including a normal CBC and ESR, with frequent follow-up and the close cooperation of the child’s parents.

Children with bone infections may have a prolonged hospitalization or home restriction during the treatment process. Home-nursing services may be necessary to assist with long-term antibiotics and wound care. Tutoring programs are often necessary if the infection occurs during the school year.

GROWING PAINS AND APOPHYSITIS

Specialized centers known as “growth plates” or “physes” control growth in the bone. Muscle tissue has no growth center but grows in response to the stretch that the elongating bone provides.

• Clinical Pearl

At times of rapid growth, the bone length may outstrip the compensatory stretch of the muscle, leading to a period of relative muscle tightness. At these times, increased force and resulting irritation occur at the muscle insertions. If the insertion is a wide area, the irritation leads to growing pains. If the muscle inserts onto a growth plate (or apophysis), the increased stretch causes growth plate irritation or apophysitis.

Apophysitis involves specific sites. The most common site is the anterior shin or tibial tubercle, called Osgood-Schlatter’s disease (OSD). Involvement of the lower pole of the patella is termed “jumper’s knee” or Sindig-Larsen-Johannson’s disease. The back of the heel bone may develop apophysitis from pull of the Achilles tendon (gastroc-soleus complex) and is called Sever’s disease.

Epidemiology

Growing pains are seen in children between ages 3 and 6. The incidence is difficult to assess since parents often do not bring their children to providers for evaluation when symptoms appear too mild.

Apophysitis tends to occur in older children (ages 11 years and older), although Sever’s may occur in younger children at the first major spurt in shoe size. Boys are affected for all apophysitides more frequently than girls (2:1). The most common type is OSD. One apophysitis may coexist with another (Tolo, 1996).

History and Physical Exam

Growing pains will present as vague pain, usually poorly localized around both knees. Rarely, the child may voluntarily limit activities. The pain will often respond to massage and analgesics such as NSAIDs or acetominophen. Constitutional symptoms should always be absent. Physical exam generally is non-focal, with no point tenderness, joint disruption,

or gait disturbance. Any positive findings should point to another diagnosis.

or gait disturbance. Any positive findings should point to another diagnosis.

• Clinical Pearl

The classical picture of growing pains is that of a normally active child during the day who runs around nonstop, without interruption of activity or limp, but who often complains bitterly at night.

The clinical picture of apophysitis is that of pain that worsens with activity, although pain may be present at rest if inflammation is significant. The pain may respond to NSAIDs and ice or heat, but relief is generally limited and short. Apophysitis always features point tenderness over the inflamed portion of the limb. In OSD the anterior shin will be markedly tender and prominent with mild erythema and swelling. There may be a limp, and range of motion of the knee will be painful, especially with extension and extension against resistance. “Jumper’s knee” can be differentiated by tenderness over the lower pole of the patella, with no significant swelling or bony prominence. Knee straightening may be painless, but resisted bending will often elicit symptoms. Sever’s disease involves tenderness over the back of the foot, directly at the end of the heel bone. There may be a reddened, prominent area with increased warmth locally as in OSD. Children will have difficulty standing on their toes but complain of most pain when duck or heel walking.

Diagnostic Studies

If the clinical picture is classic for either growing pains or true apophysis, extensive laboratory or radiographic testing may not be necessary. If there is a history of trauma or any systemic illness, providers should obtain x-rays of the limb (or limbs) to rule out fracture, infection, or another less common entity.

For growing pains, x-rays and laboratory studies are by definition negative and unnecessary unless the pain persists for an extended period. Radiographs of the painful area in OSD or other apophysitis will show elevation and widening of the growth plate and possibly fragmentation of the bone. It may be difficult to differentiate OSD from acute fracture of the tibial tubercle.

Management

Growing pains will almost always respond to gentle massage, ice or heat, and occasionally analgesics. Gentle stretching may be useful, particularly in long-standing cases. Episodes will typically be of limited duration, lasting no more than 6 to 9 months, and recurrence is extremely unusual. If the pain is persistent, or if it worsens in the face of other clinical findings, the provider should evaluate the child with a complete work-up including x-rays, bone scan, and screening labs. The clinician should evaluate the child with persistent episodes of waking from sleep for possibly non-orthopedic etiology, such as night terrors or recurrent muscular spasm.

Treatment of apophysitis includes anti-inflammatory doses of NSAIDs, gentle stretching, and short-term activity modification. Bracing can be helpful, with a patellar-stabilizing (“donut hole”) sleeve knee brace for OSD or “jumper’s knee” and heel wedges for Sever’s disease. In severe cases, the child may need short-term casting to allow the inflammation to completely resolve. Although by definition all apophysitis will resolve at the cessation of growth, early aggressive treatment is advocated to minimize the painful course and to allow as quick a return to normal activity as possible. As with growing pains, recurrence is highly unusual.

Although most cases of apophysitis and growing pains can be treated at the primary care level, clinicians should refer recalcitrant cases for further evaluation and possibly more aggressive therapy. Providers should reassure parents and children that the pain is self-limited and will resolve with conservative care, but that any bony deformity is permanent.

SLIPPED CAPITAL FEMORAL EPIPHYSIS (SCFE)

Providers should suspect slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), another surgical emergency, in all adolescents with groin or thigh pain. SCFE also may present as knee pain. In severe cases, the pain may mimic an acute fracture of the hip and may progress to long-standing problems such as bone collapse or arthritis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree