Key Clinical Questions

Introduction

Although women of childbearing age represent a younger and generally healthy population, currently 40% of women entering pregnancy have chronic medical conditions. The rise in the rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes, combined with modern medical technology, have resulted in pregnancy in older and sicker women. It is important to consider how diseases and their treatment may impact pregnancy and how pregnancy may affect certain diseases. This chapter will focus on the most common medical problems in pregnancy.

Cardiac Diseases

During pregnancy, blood volume and cardiac output rise, and systemic vascular resistance decreases. Later in pregnancy the gravid uterus may compress the inferior vena cava, thereby significantly decreasing preload in the supine position. Cardiac output increases 40% by mid-pregnancy until labor and delivery when it increases further. Increased blood volume and left atrial dimensions may contribute to the increase in palpitations and supraventricular tachycardia. If the heart is damaged either by congenital heart disease or by cardiomyopathy, the increase in cardiac work cannot occur as effectively. In addition, just after delivery, with a uterine contraction a liter of blood can be shunted from the uterus into the general circulation. Cardiac lesions associated with a fixed cardiac output will not tolerate this sudden increase in volume. Hence, the most common complications in late pregnancy or immediately after delivery include pulmonary edema and, less commonly, right heart failure. In addition, the risk of a fetus developing congenital heart disease is increased if the mother has the same problem (for example, 1:4 in tetralogy of Fallot and 1:15 in atrial septal defects). Patients with severe pulmonary hypertension and/or Eisenmenger syndrome characterized by a reversed right-to-left shunt have increased mortality rates, especially during the first 48–72 hours postpartum.

Systemic vascular resistance decreases about 25%, which may improve any cardiac condition that benefits from after-load reduction such as aortic insufficiency. When compression of the inferior vena cava decreases venous return to the heart, patients with preload-dependent cardiac conditions such as aortic stenosis or poor left ventricular function may experience hypotension, especially when supine. Because the increased cardiac demands peak at 24 to 28 weeks of gestation, cardiac decompensation may become evident at the end of the second trimester.

Labor and delivery may be associated with cardiac decompensation when one to two units of blood leave the uteroplacental circulation during contraction. When the contraction ceases, the blood returns to the uteroplacental circulation.

Patients with peripartum cardiomyopathy that occurs in the third trimester and up to six months following delivery have symptoms and signs consistent with congestive heart failure. Approximately, one-third of these patients will completely recover, one-third will have chronic congestive heart failure, and one-third may have a progressive cardiomyopathy that may require cardiac transplantation in severe cases.

Postpartum fluid shifts occur during involution of the uterus and the low-resistance circulation of the placenta, postpartum blood loss, and increase in preload when the uterus no longer compresses the inferior vena cava.

Acute myocardial infarction is a rare complication during pregnancy. Coronary dissection with normal coronary arteries on angiography is more common in the peripartum or postpartum period. Patients with longstanding diabetes may develop myocardial ischemia during pregnancy. Antiphospholipid antibody-associated arterial thrombosis and arterial vasospasm and cocaine ingestion may also result in myocardial infarction.

Finally, women with artificial heart valves who receive anticoagulant treatment will need to continue to do so during pregnancy. Decision about type of anticoagulation requires a careful risk-benefit discussion, and should not include warfarin during the first trimester or toward term. Careful monitoring to achieve consistently therapeutic levels of anticoagulation is important. Ideally these patients should receive care and obstetric at a tertiary medical center that can provide combined cardiac and obstetric antenatal care.

Infectious Diseases

Although pregnant women develop the same infections as nonpregnant individuals, there are important pregnancy-related issues that should be considered in the evaluation and treatment of these patients. Pregnant women are predisposed to certain infections and pregnancy may alter the course of some infections. Clinicians need to consider maternal-fetal transmission and the impact of some antibacterial or antiviral drugs upon the fetus.

A primary systemic infection with toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, syphilis, and parvovirus can be associated with congenital malformations and disease. Primary infection with coccidiomycoses, especially common in the southwestern United States, can be complicated by fungal meningitis, otherwise rare in a normal host.

Fever, mild uterine tenderness, and contractions may suggest chorioamnionitis or infection of the amniotic sac and fluid. The diagnosis is made by consultation with an obstetrician and consideration of amniocentesis (positive Gram stain, amniotic fluid glucose usually < 15 mg/dL). Treatment may require delivery.

Infection of the endometrium, an ascending polymicrobial infection, occurs in the postpartum period. Risk factors include prolonged rupture of membranes, delivery requiring instrumentation, and cesarean section, especially unplanned or emergent. Obstetricians can advise on the best antibiotic regimen depending on early postpartum endometritis (within the first 48 hours) and later endometritis (more than one week postpartum). Septic pelvic thrombophlebitis may be considered when a patient has persistent fevers despite an appropriately treated postpartum endometritis. If pelvic thrombosis is not seen by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance venography (MRV) of the pelvis in a patient who does not appear to be ill, alternative diagnoses such as abscess, hematomas, and necrotizing fasciitis should be considered.

Acute pyelonephritis complicates 1–2% of all pregnancies and can be associated with significant maternal and fetal morbidity. Untreated asymptomatic bacteriuria is associated with a 25% incidence of pyelonephritis. Therefore, asymptomatic bacteriuria in a pregnant patient should always be treated.

Pyelonephritis is most common during the second half of the pregnancy as a result of increased ureteral obstruction and urinary stasis, which result from both mechanical and hormonal factors. It is usually unilateral, affecting the right kidney more frequently because of uterine dextrorotation. Prior history of pyelonephritis, urinary tract malformations, and calculi put patients at a higher risk for development of an acute episode of pyelonephritis during pregnancy.

Pyelonephritis most commonly presents with systemic signs and symptoms including flank pain, fever, costovertebral angle tenderness, shaking chills, nausea, vomiting, and less often with features of cystitis, such as dysuria and frequency.

Laboratory findings generally include a positive urine culture and pyuria on urinalysis. Additional laboratory studies should include a complete blood cell count and serum chemistry evaluation. Transient renal insufficiency with as much as 50% decrease in creatinine clearance is observed in about a quarter of all patients. Although blood cultures are often obtained in these patients, their utility is limited. Pathogens isolated from blood cultures rarely differ from those found in the corresponding urine culture. Blood cultures are recommended in cases that are complicated by sepsis, temperature of at least 39°C, or respiratory distress syndrome.

Ovarian vein thrombosis may present as fever and flank pain and so should be considered in patients suspected of having pyelonephritis who have normal urinalysis.

Pyelonephritis has unique complications in pregnancy. These include development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which can occur in up to 10% of patients. It is more common in patients with pyelonephritis and preterm labor who are being treated with beta-agonist tocolysis. Acute pyelonephritis during pregnancy is also associated with preterm delivery, with reported incidence between 6% and 50%, depending upon gestational age at presentation.

Early aggressive treatment of pyelonephritis is important in preventing complications. The current standard of care includes hospitalization and parenteral antibiotics. Initial antibiotic choice is empiric. Several equally efficacious regimens are available and are summarized in Table 223-1. Most patients respond within 72 hours. Therapy with the best oral agent, according to culture and sensitivity testing, should be continued to complete a two-week course. Most experts recommend that suppressive therapy should be continued until delivery for all pregnant patients with a single episode of pyelonephritis. Prophylactic regimens include nitrofurantoin 100 mg once daily or cephalexin 250 mg once daily taken by mouth.

|

Although most often reported as a mild illness, listeriosis deserves mention here because of the increased incidence in pregnancy and propensity for fatal disease in the fetus. The incidence of listeriosis in pregnancy is 12 per 100,000, compared with a rate of 0.7 per 100,000 in the general population.

Although severe maternal illness from listeriosis has been reported, it is rare. In most cases, maternal illness is mild and sometimes even asymptomatic. Fever, chills, back pain, and flu-like symptoms are most commonly reported. Illness can resolve spontaneously and the diagnosis be missed if cultures are not obtained. Patients with comorbidities, such as a history of splenectomy, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, steroid use, diabetes, or use of immunosuppressive medications, are at increased risk for severe maternal illness, which includes meningitis and meningoenchepalitis.

In contrast to maternal illness, fetal and neonatal infection is severe and frequently fatal, with a case fatality rate of 20% to 30%. Neonatal listerial infection can cause pneumonia, sepsis, or meningitis. A characteristic severe in utero infection, granulomatosis infantiseptica, may result from transplacental transmission, characterized by widespread abscesses and/or granulomas in multiple internal organs. Most infants with this condition are either stillborn or die soon after birth.

Diagnosis of listerial infection can only be made by culturing the organism from a sterile site such as blood, amniotic fluid, or spinal fluid. Vaginal or stool cultures are not helpful in diagnosis because some women are carriers but do not have clinical disease. Gram stain is useful in only about 33% of cases, both because Listeria is an intracellular organism and can be entirely missed, and because the organism can resemble pneumococci (diplococci), diphtheroids (Corynebacteria), or Haemophilus species.

Pregnant women with isolated listerial bacteremia can be treated with ampicillin alone (2 g IV every four hours). Patients who are allergic to penicillin can be skin tested and desensitized, if necessary, or treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (5 mg/kg of the trimethoprim component IV every six hours). Vancomycin has also been used in case reports of listerial infection.

Acute bronchitis usually refers to a self-limited respiratory illness characterized by the predominance of a productive cough in a patient with no history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and no evidence of pneumonia. Most cases of acute bronchitis have a viral etiology; however, atypical bacteria including Bordetella pertussis, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae are important causes. The etiologic pathogen is isolated from the sputum in only a minority of patients.

No studies have particularly looked at the course of acute bronchitis in pregnancy. A retrospective cohort study found an association between placental abruption and acute respiratory illnesses including acute bronchitis among white women.

Most pregnant patients with acute cough syndromes require no more than reassurance and symptomatic treatment with inhaled beta-agonists. A chest X-ray should be performed if clinically indicated. Antimicrobial therapy may be considered in patients when a treatable pathogen is identified or in epidemic settings to limit transmission. Table 223-2 includes suggested antimicrobial regimens for pregnant patients.

| Pathogen | Comments | Treatment Options in Pregnancy |

|---|---|---|

| Influenza virus | Precipitous onset with fever, chills, headache, cough and myalgias | Antiviral agents recommended for treatment of influenza have either very little or concerning pregnancy safety data. With the H1N1 pandemic, pregnant women have been found to be at increased risk of complications and treatment with oseltamivir 75 mg orally twice daily is recommended. |

| Parainfluenza virus | Epidemic may occur in fall. Croup in a child at home suggests the presence of this organism. | No treatment available |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | Outbreaks occur in winter or spring. Approximately 45% of adults exposed to an infant with bronchiolitis become infected. | No treatment available |

| Coronavirus | Severe respiratory symptoms may occur. | No treatment available |

| Adenovirus | Infection is clinically similar to influenza, with abrupt onset of fever. | No treatment available |

| Rhinovirus | Fever is uncommon, infection is generally mild. | No treatment available |

| Bordetella pertussis | Incubation period is one to three weeks. Posttussive vomiting may be present. Fever is uncommon. |

|

| Mycoplasma pnemoniae | Gradual onset over two to three days of headache, fever malaise, and cough. Wheezing may occur. Dyspnea is uncommon. | Azithromycin for five days (500 mg on day 1, 250 mg days 2–5) or no therapy |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | Gradual onset of cough with preceding hoarseness | Azithromycin for five days (500 mg on day 1, 250 mg days 2–5) or no therapy |

There are no compelling data suggesting improved outcomes of acute bronchitis as a result of treatment with antibiotics.

The incidence of pneumonia requiring hospitalization in pregnancy is between 2.6 to 15.1 per 10,000 deliveries, a rate comparable to that seen in nonpregnant women of a similar age. Pregnancy is associated with reduction in cell-mediated immunity, which places pregnant women at an increased risk of severe pneumonia and disseminated disease from some atypical pathogens such as herpes virus, influenza, varicella, and coccidioidomycosis.

The etiology of pneumonia in pregnancy is similar to the nonpregnant population, with streptococcus pneumoniae being the most commonly isolated organism. Other causes include Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, Legionella spp, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, chlamydia and viruses. Among patients requiring admission to intensive care units, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae play an important role.

Mothers who develop pneumonia are more likely to have coexisting medical problems including asthma, drug abuse, anemia, and HIV infection. The use of corticosteroids for enhancement of fetal lung maturity and tocolytic agents has also been associated with antepartum pneumonia.

Pregnant women with pneumonia present no differently than nonpregnant women and pneumonia should be considered in any woman presenting with fever, cough, sputum production, chills, rigors, dyspnea, and pleuritic chest pain. Occasionally, nonrespiratory symptoms such as vomiting, abdominal pain, and fever may predominate.

A chest radiograph should be performed in all patients suspected to have pneumonia. Laboratory data should include a complete blood count, serum chemistries for hepatic, renal, glucose evaluation, assessment of oxygenation, and two sets of blood cultures; however, blood cultures may be positive only 7–15% of the time. The American Thoracic Society does not recommend routine performance of sputum culture and Gram stain. However, if a drug-resistant pathogen or an organism not covered by usual empiric therapy is suspected, sputum culture should be obtained. HIV status should be reviewed for all pregnant women with pneumonia and testing should be offered if it has not previously been done. Testing for pneumocystis carinii infection should occur in all HIV positive women who present with pneumonia.

The differential diagnosis for a pregnant woman presenting with symptoms of pneumonia is varied. Pulmonary embolism can present identically to an acute pneumonia with dyspnea, cough, chest pain, fever, and chest X-ray infiltrates. Aspiration, chemical pneumonitis, amniotic fluid embolism, and pulmonary edema related to sepsis, tocolysis, or preeclampsia can also present similarly.

Pregnancy increases the risk of maternal complications from pneumonia, including the need for mechanical ventilation. Respiratory failure due to pneumonia is the third leading indication for intubation in pregnancy. Other maternal complications include pulmonary edema, bacteremia, empyema, pneumothorax, and atrial fibrillation. Pregnancies complicated by acute respiratory illnesses, including viral and bacterial pneumonia have been shown to be associated with placental abruption. Increased rates of preterm labor and delivery before 34 weeks of gestation have also been described.

The neonatal mortality rate due to antepartum pneumonia ranges from 1.9% to 12%, with most mortality attributable to complications of preterm birth. Although most cases of pneumonia in pregnancy are caused by organisms that do not affect the fetus except through their effects on maternal status, some organisms, such as varicella and CMV may present specific risks to the fetus. The fetus may also be at risk from maternal conditions that predispose to pneumonia, such as anemia or HIV infection.

While no specific guidelines exist to help assess severity and the need for hospitalization in pregnant women, it is best to ensure adequate maternal oxygenation (oxygen saturation ≥ 95% or pO2 ≥ 70 mm Hg) and fetal well-being before considering outpatient treatment.

Several recommendations exist for treatment of pneumonia in pregnancy. Table 223-3 summarizes some suggested recommendations based upon ATS guidelines. Although levofloxacin and doxycycline are often recommended in the treatment of pneumonia in the nonpregnant population, these drugs should be avoided in pregnancy. Clarithromycin has shown to have adverse effects in animal trials at doses equivalent to 2 to 17 times the maximum recommended human dose. It is therefore best avoided in pregnancy, with use limited to those cases in which no alternative therapy is appropriate.

| Type of Pneumonia | Recommended Antibiotics Acceptable for Use in Pregnancy | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Ceftriaxone (2 g IV daily) or cefotaxime or ampicillin/sulbactam (3 g IV every 6 hours) | Avoid tetracycline and doxycycline in pregnant or breastfeeding mothers. |

|

| Antipneumococcal fluoroquinolone may be used in nonpregnant patient but generally avoided in pregnancy or breastfeeding mothers |

| If concern for MRSA, add vancomycin (15 mg/kg every 12 hours) | |

| Hospital-acquired pneumonia/health care–associated pneumonia/ventilator-associated pneumonia | Ceftriaxone (2 g IV daily) or ampicillin/sulbactam (3 g IV every 6 hours) | Efficacy of once daily dosing for gentamycin in pregnancy not well established. |

| Organisms: | If concern for MDR: | |

| Aerobic gram negatives (P. aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter sp.) |

| |

| Gram positive cocci Staphylococcus aureus, esp. methicillin resistant (MRSA) |

| |

| Oropharyngeal commensals (viridans group strep, coagulase negative staph, Neisseria sp, Corynebacterium sp) | Vancomycin (15 mg/kg every 12 hours) | |

| Clindamycin or Penicillin | |

| Varicella pneumonia | Acyclovir IV 10 mg/kg every 8 hours |

With appropriate therapy, an improvement can be expected in 72 hours, after which the regimen can be changed to an oral medication to complete 10–14 days therapy.

In general, pregnancy does not affect the diagnosis or clinical course of viral hepatitis. It has been reported, however, that acute hepatitis may be more severe with hepatitis E. The differential diagnosis includes other common causes of liver dysfunction such as biliary obstruction, drug-induced liver disease, as well as liver diseases uniquely associated with pregnancy such as acute fatty liver, preeclampsia or HELLP (hemolysis, elevated live enzymes, and low platelets), and cholestasis of pregancy.

As a form of disseminated primary herpes infection, usually Herpes simplex type 2, HSV has been reported in the second and third trimester. Pregnant patients may have characteristic mucocutaneous lesions and anicteric liver failure due to severe hepatocyte injury with extreme elevations of serum transaminases, an increased prothrombin time, and only mildly elevated serum bilirubin. If prescribed early in the course of illness, acyclovir may be effective in ameliorating the course of illness.

Pulmonary Disease

Normal pregnancy is characterized by an increase in minute ventilation, due to an increase in tidal volume but not of respiratory rate. This results in a change in arterial blood gases with the average PaO2 in pregnancy 100 mm Hg at sea level and PCO2 in the range of 28 and 32 mm Hg. An ABG with a PaO2 of 79 mm Hg and a PCO2 of 40 mm Hg in a pregnant female is very abnormal. Because fetal hemoglobin has a different oxygen dissociation curve from adult hemoglobin, the fetus requires that maternal oxygenation remains greater than a PaO2 of 70 mm Hg. This means that maternal oxygen saturation should be greater than 95%.

Pregnant women have an increased risk for pulmonary edema due to the 50% increase in blood volume that is predominantly achieved through an increase in plasma free water and a lower oncotic pressure. Pyelonephritis, medications that are used to stop preterm labor, and preeclampsia may precipitate pulmonary edema. Pregnancy-associated pulmonary edema often responds to withdrawal of the precipitating cause and a low diuretic dose.

Dyspnea of pregnancy usually begins in the middle of gestation as the patient’s increased perception of dyspnea. These patients should have a completely normal physical examination, oxygenation, chest X-rays, and pulmonary function testing.

If shortness of breath occurs at 24–48 weeks when blood volume reaches its maximum, underlying heart disease should be considered.

A rare cause of dyspnea unique to pregnancy is amniotic fluid embolism occurring during the third trimester but usually during delivery. Rapid and progressive respiratory failure may be associated with hemodynamic instability and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. This is a diagnosis of exclusion and treatment is supportive care.

The presentation of VTE may be subtle during pregnancy due to the absence of other co-morbidities. See below.

Asthma affects 3.7% to 8.4% of all pregnancies and is one of the most common serious medical complications encountered in pregnancy in the United States. Asthma may develop during gestation triggered by an upper respiratory infection with persistent bronchospasm or be triggered due to reflux or sinusitis, both increased during pregnancy.

The course of asthma is usually unpredictable in pregnancy and numerous studies have suggested that a third of the patients improve, a third remain the same, and another third worsen. Factors contributing to improvement may be the pregnancy-associated rise in serum cortisol or the increase in progesterone that acts as a potent smooth muscle relaxant. Several factors may be responsible for worsening. Gestational rhinitis, bacterial sinusitis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease, all of which occur at an increased incidence in pregnancy, may worsen asthma control in the gravid state.

Most studies have shown that well-controlled pregnant patients with asthma do not have a significantly higher rate of adverse outcomes than those without asthma. However, patients with poorly controlled asthma are more likely to have miscarriages or therapeutic abortions, infants with low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction, and are more likely to undergo cesarean section. Preterm delivery and maternal hypertension have also been noted in poorly controlled women with asthma, but these risks have not been shown consistently and may partly be related to use of systemic steroids in these patients. Preeclampsia has also been associated with severe asthma in some studies.

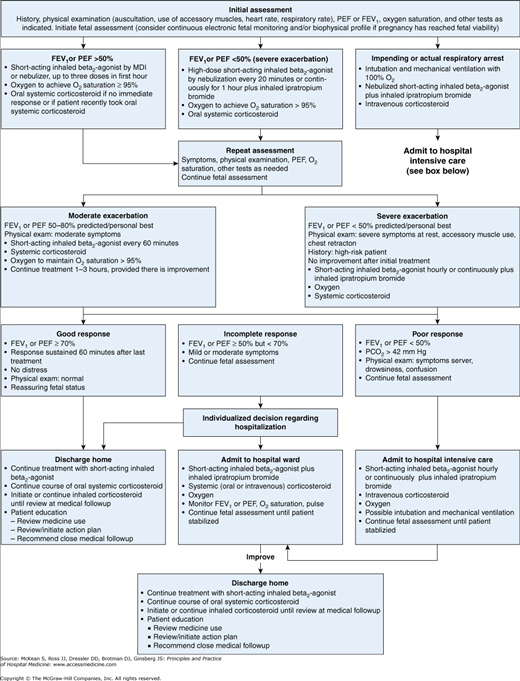

Management of asthma in pregnancy does not significantly differ from the nonpregnant patient. Table 223-4 discusses the use and safety of commonly used asthma medications in pregnancy. While dealing with an acute asthma exacerbation in a pregnant woman, it is of vital importance to recognize that normal CO2 in pregnancy is 28–32 mm Hg, which is lower than the nongravid state. Therefore, a tachypneic pregnant patient with a PaCO2 above this range might be in impending respiratory failure. Figure 223-1 shows the recommendations for assessment and management of acute asthma exacerbation in the hospital setting. These are based on the NAEP guidelines for asthma management in pregnancy.

| Medication Type | Data Suggests Use Justifiable When Indicated | Data Suggests Use Justifiable in Rare Circumstances | Data suggests Use Almost Never Justifiable | Useful Review Articles and Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-acting inhaled beta-2 adrenergic agonists |

| Published experience with these drugs in animals and humans suggests that beta-sympathomimetics do not increase the risk of congenital anomalies. Albuterol is the most studied of these agents. Metaproterenol is the second most studied. NAEP guidelines for the management of asthma in pregnancy can be obtained through the NHLBI at [PubMed: 16946229] [PubMed: 16443141] [PubMed: 10830999] | ||

| Long-acting inhaled beta-2 adrenergic agonists |

| Of the few studies that have examined pregnancy outcomes with prenatal exposure to long-acting beta-2 agonists, no adverse events were found. However, due to small numbers in the studies, and because animal models have shown delayed ossification, use of this agent should be reserved for patients who have failed low potency steroids and/or cromolyn alone. [PubMed: 11945116] [PubMed: 9746382] | ||

| Xanthines |

| These drugs do not appear to be human teratogens. The clearance of aminophylline and theophylline is increased in pregnancy but may be variable. If daily dose exceeds 700 mg, blood levels should be checked for optimal dosing. [PubMed: 15695974] [PubMed: 16443141] | ||

| Inhaled corticosteroids | Low potency: beclomethasone dipropionateC Medium potency: trimacinolone acetonideC High potency: fluticasone propionateC budesonideB flunisolideB | Beclomethasone and budenoside are the most widely studied of the inhaled corticosteroids in pregnancy and should be considered the preferred inhaled steroids in pregnancy. Relatively little of these agents are absorbed and human data has not suggested any teratogenic effects of these agents. Triamcinolone is the next most studied inhaled steroid in pregnancy, with this limited experience suggesting no adverse pregnancy effects Fluticasone has not been studied in pregnancy; however its minimal systemic absorption and the safety of the other steroids in pregnancy make its use in pregnancy generally felt to be justifiable. [PubMed: 16004676][PubMed: 16775906] | ||

| Systemic steroids |

| Most data suggest that systemic steroids do not present a teratogenic risk in human pregnancy. In doses equivalent to prednisone 25 mg/day, they do not cross the placenta because of placental metabolism (the same is not true for betame-thasone or dexamethasone). Even in higher doses, the effect of hydrocortisone or prednisone on the fetus in terms of suppression of the hypothalmo-pituitary-adrenal axis is minimal. Several case control studies have found a significant association with first trimester steroid use and oral clefts; however this was not seen in cohort studies. Even if this association is real, the risk is still small. For every 1000 embryos exposed during the susceptible days of first trimester, probably no more than three will develop an oral cleft. The background risk in the general population is 1 per 1000. Therefore, the benefits of controlling a life-threatening disease make steroid use when indicated in the first trimester still generally justifiable. [PubMed: 15013068] | ||

| Mast cell stabilizers |

| Human and animal data suggest these agents are not teratogens. These agents are virtually not absorbed through mucosal surfaces and the swallowed portion is largely excreted in the feces. | ||

| Inhaled anticholinergics | IpratropiumB | Although animal studies are reassuring, no published human data exists. These drugs are poorly absorbed by the bronchial mucosa so fetal exposure is likely minimal. | ||

| Leukotriene inhibitors |

| Zileuton B | Although these agents have reassuring animal data and are widely used in pregnancy because of the FDA category B rating, published safety data in human pregnancy is limited at this point. Their use should be limited in pregnancy to those cases in which a woman has had significant improvement in asthma control with these medications prior to becoming pregnant that was not obtainable through other methods. Zileuton is different than other agents in this class as there is some animal data to suggest association with adverse pregnancy outcomes. | |

| Antihistamines |

|

|

| |

| Cough |

| |||

| Nasal congestion |

|

|

Figure 223-1

Management of asthma exacerbations during pregnancy and lactation: Emergency department and hospital-based care. FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; MDI, metered-dose inhaler; PCO2, carbon dioxide partial pressure; PEF, peak expiratory flow. (From the Asthma and Pregnancy Report. NAEPP Report of the working group on Asthma and Pregnancy. NIH publication No. 93-3279. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human services; National Institutes of Health; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 1993. Available from URL: .)

While asthma exacerbations are rare in labor and delivery, it is important to ensure that asthma medications are not discontinued through labor and delivery. Most drugs used for asthma treatment can be safely used in breastfeeding women. Whether breastfeeding decreases the likelihood of the development of asthma in offspring is as yet controversial, but it does appear to decrease atopy.

Pleural effusions can be caused by a variety of conditions, both specific and unrelated to pregnancy. Physiologic changes of pregnancy, including an increased blood volume and decreased colloid osmotic pressure, promote transudation of fluid into the pleural space. Benign postpartum pleural effusions have been noted on chest radiographs and ultrasound studies after normal vaginal delivery with an incidence of about 25%. Pregnancy-specific conditions that predispose to pulmonary edema such as preeclampsia, amniotic fluid embolism, chorioamnionitis, or endometritis, may also result in pleural effusion.

Diagnostic approach is largely guided by findings on history and physical exam and conditions being considered in the differential. A diagnostic thoracocentesis should always be considered in the presence of fever, hemoptysis, weight loss, or when hemothorax or emphysema is suspected.

Management usually involves treatment of the underlying condition. Rarely, a therapeutic thoracentesis may be necessary, particularly in case of a large (eg, TB) or rapidly accumulating effusion (eg, malignancy). Presence of blood, pus, or chylous effusion warrants placement of a thoracostomy tube. While performing these procedures in pregnancy, it is important to remember that the diaphragm is about 4–5 cm elevated and a higher approach may be needed.