CHAPTER 11 Common Analgesics

Description

Terminology and Subtypes

Common analgesics is a broad term used to refer to several classes of medications used to manage pain, which in the context of this chapter includes both nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), simple analgesics, and muscle relaxants. Although muscle relaxants are not classified as analgesics, they are often used to alleviate symptoms of low back pain (LBP) and therefore also included in this chapter. The term common analgesics is also intended to differentiate these medications from opioid analgesics and adjunctive analgesics, which are discussed in Chapters 12 and 13, respectively. The term non-opioid analgesic is also used to describe medications with analgesic properties other than opioids.

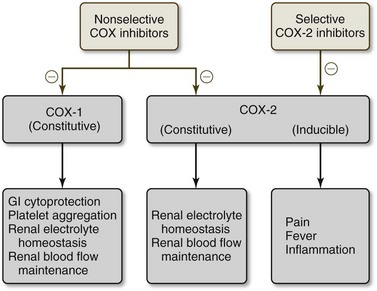

Older NSAIDs are sometimes termed traditional, nonselective, or nonspecific NSAIDs because they inhibit both the cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 and COX-2 enzymes. Newer NSAIDs are commonly known as COX-2 inhibitors (sometimes shortened to coxibs), selective, or specific NSAIDs because they block only the COX-2 isoenzyme.1,2 Simple analgesics is a somewhat vague term of exclusion that typically refers to analgesics that are neither opioid analgesics nor adjunctive analgesics; in this chapter, the term is synonymous with acetaminophen. Muscle relaxants can be categorized as either antispasmodic or antispasticity.3 Muscle spasm refers to an involuntary muscle contraction, whereas spasticity refers to persistent muscle contraction.

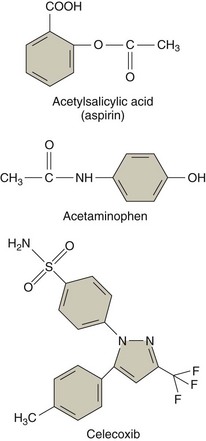

The two main subtypes of NSAIDs are nonselective and selective (Figure 11-1). Within nonselective NSAIDs, there are salicylates (e.g., aspirin, diflusinal, salsalate), phenylacetics (e.g., diclofenac), indoleacetic acids (e.g., etodolac, indomethacin, sulindac, tolmetin), oxicams (e.g., piroxicam, meloxicam), propionic acids (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen, ketorolac, oxaprozin), and naphthylkanones (e.g., nabumetone). Within selective NSAIDs, there are only coxibs (e.g., celecoxib, rofecoxib, valdecoxib, and etoricoxib).

Figure 11-1 Molecular structures of several analgesics.

(From Wecker L: Brody’s human pharmacology, ed. 5. St. Louis, 2010, Mosby.)

Muscle relaxants are a heterogeneous group of medications divided into antispasmodics and antispasticity medications.3 Antispasmodic muscle relaxants include two main categories, benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepines. Benzodiazepine antispasmodics have many properties and are used as skeletal muscle relaxants, sedatives, hypnotics, anticonvulsants, and anxiolytics; they include medications such as diazepam, fludiazepam, and tetrazepam. Nonbenzodiazepine antispasmodics act at the brain or spinal cord level to decrease muscle spasm associated with LBP and include medications such as cyclobenzaprine and flupirtin. Antispasticity muscle relaxants reduce spasticity associated with upper motor neuron (UMN) disorders and include medications such as dantrolene and baclofen. Simple analgesics include commonly used medications such as acetaminophen.

The World Health Organization generally advocates using a graduated approach to medication use for the management of pain, including chronic LBP (CLBP). This concept is illustrated by the “pain ladder” wherein simple analgesics and NSAIDs occupy the first rung and opioid analgesics occupy higher rungs. The pain ladder should only be climbed if first-line medications prove ineffective for achieving adequate pain management.3–7

History and Frequency of Use

Common analgesics have been used to treat LBP for many decades. Predecessor herbal ingredients (e.g., willow bark for aspirin), have been used for hundreds of years for relief of many painful conditions, including LBP.8

NSAIDs are the world’s most frequently prescribed medications.9,10 A 2000 US Medical Expenditure Panel Survey11 found that 44 million prescriptions were written for 25 million patients with LBP, both acute and chronic. Of these, 16% were for nonselective NSAIDs, 10% were for COX-2 inhibitors, and 19% were for muscle relaxants. Most prescription NSAIDs (60%) were ibuprofen and naproxen, and most muscle relaxants (67%) were cyclobenzaprine, carisoprodol, and methocarbamol. A longitudinal study by Cherkin and colleagues12 found that 69% of patients with LBP in the primary care setting were prescribed NSAIDs, 35% received muscle relaxants, 4% received acetaminophen, and only 20% were not prescribed medications. A review of the University of Pittsburgh Healthcare System in 2001 found that 53% of men and 57% of women presenting with LBP were prescribed an NSAID13; more severe pain tended to be treated with opioids or muscle relaxants. NSAIDs were prescribed for 27% of patients, opioids and NSAIDs for 26%, opioid and other analgesics for 9%, and COX-2 inhibitors for 3%. A study in Sweden of 302 patients with CLBP reported that patients took an average of two different medications for that condition.14 The most common class of drug consumed for CLBP was analgesics (59%), followed by NSAIDs (51%), muscle relaxants or anxiolytics (11%), and COX-2 inhibitors (5%). A study of health care use in patients with mechanical LBP enrolled in Kaiser Permanente Colorado indicated that 31% of patients had a claim for NSAIDs.15

Procedure

Management of CLBP with common analgesics (as defined above) involves a consultation with a physician who will take a detailed medical and LBP-focused history, and inquire about current medication use. If deemed appropriate, the physician will then prescribe a common analgesic along with instructions about dosage, timing, side effects, and interactions with other medication; this information may also be provided by the dispensing pharmacist (Figure 11-2). A follow-up appointment will likely be scheduled within a few weeks so that the physician can determine whether the common analgesic is achieving the desired effect, adjust the dosage if necessary, change the medication in favor of another common analgesic or different class of medication if required, and provide education about other strategies for managing CLBP.

Theory

Mechanism of Action

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

NSAIDs function through various degrees of reversible blockade of COX isoenzymes, thus blocking the inflammatory cascade of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins, which mediate inflammation and sensitize peripheral nociceptors.16 Aspirin is a type of salicylic NSAID with irreversible blockade of both COX isoenzymes, though it binds 170 times more to COX-1 than to COX-2, resulting in inhibition of prostaglandins and platelet aggregation. The exact mechanism of action for non-aspirin salicylates is currently unknown. Another mechanism involved with NSAIDs is inhibition of neutrophil function and phospholipase C activity, which increases intracellular calcium levels and production of arachidonic acid metabolites such as prostaglandins. These mechanisms account for both the anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties of NSAIDs (Figure 11-3).

Simple Analgesics

Acetaminophen possesses both analgesic and antipyretic properties. It is classified as a para-aminophen derivative that weakly inhibits COX isoenzymes, thereby selectively inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis without inhibiting neutrophils. The antipyretic effects of acetaminophen are likely due to its action in the heat regulation center located in the hypothalamus.16

Muscle Relaxants

This heterogeneous group of medications generally acts by inhibiting central polysynaptic neuronal events, which indirectly affect skeletal muscle.17 Antispasticity muscle relaxants act on the central nervous system (CNS) to decrease UMN spasticity pathways. Baclofen is thought to act as a gamma-butyric acid (GABA) analog at GABA-B receptors, thus inhibiting presynaptic calcium influx and excitatory neurotransmitters. Tizanidine acts as an α2-adrenergic agonist that is thought to inhibit presynaptic motor neurons. The mechanism through which diazepam relaxes skeletal muscle is currently unknown, but is thought to be related to its action on postsynaptic spinal cord GABA transmission. Antispasmodic muscle relaxants act centrally through currently unknown mechanisms. Cyclobenzaprine is thought to act on the brainstem, whereas metaxalone may work by inducing generalized depression of CNS activity.

Indication

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

The primary indications for NSAIDs are generalized muscle aches and pains, soft tissue injuries, and arthritis.17 NSAIDs can be used for any type of CLBP.

Simple Analgesics

The primary indications for acetaminophen are mild muscular aches, arthritis, and fever.17 Acetaminophen can be used for any type of CLBP.

Muscle Relaxants

The primary indications for cyclobenzaprine, metaxolone, methocarbamol, and carisoprodol are acute painful musculoskeletal conditions.16 Baclofen and tizanidine are indicated for spasticity associated with UMN disorders, but are frequently used off-label for painful musculoskeletal conditions. Diazepam is indicated for UMN muscle spasticity and local painful musculoskeletal spasm, as well as anxiety. Because the true mechanism of action on muscle spasm is unknown, the sedating side effects are often used to improve sleep. Muscle relaxants are mostly used for acute LBP or acute exacerbations of CLBP, rather than prolonged CLBP.

Assessment

Before receiving common analgesics, patients should first be assessed for LBP using an evidence-based and goal-oriented approach focused on the patient history and neurologic examination, as discussed in Chapter 3. Additional diagnostic imaging or specific diagnostic testing is generally not required before initiating this intervention for CLBP. Prescribing physicians should also inquire about medication history to note prior hypersensitivity, allergy, or adverse events with similar drugs, and evaluate contraindications for these types of drugs. Clinicians may also order a psychological evaluation if they are concerned about the potential for medication misuse or potential for addiction in certain patients.

Efficacy

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

A CPG from Belgium in 2006 found evidence that NSAIDs are not more effective than other conservative approaches including physical therapy, spinal manipulation therapy (SMT), or back school.18 That CPG found low-quality evidence that NSAIDs are more effective than acetaminophen or placebo. That CPG concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support the efficacy of NSAIDs for CLBP. That CPG also found no evidence to support the efficacy of aspirin for CLBP.18

A CPG from the United Kingdom in 2009 found insufficient evidence to support the long-term use of NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors for CLBP.19 That CPG recommended NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors as second choice medications only when acetaminophen was not effective for CLBP.19

A CPG from Europe in 2004 found strong evidence to support the efficacy of NSAIDs with respect to improvements in pain for up to 3 months in patients with CLBP.3 That CPG therefore recommended the short-term use of NSAIDs for CLBP.3

A CPG from Italy in 2007 found evidence to support the efficacy of NSAIDs with respect to improvements in pain.20 That CPG also found evidence that different NSAIDs are equally effective.

The CPG from the United States in 2007 found moderate evidence to support the use of NSAIDs for patients with CLBP.21 That CPG also found insufficient evidence to estimate the efficacy of aspirin for CLBP.21

Findings from the above CPGs are summarized in Table 11-1.

TABLE 11-1 Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations on Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs for Chronic Low Back Pain

| Reference | Country | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| NSAIDs | ||

| 18 | Belgium | Insufficient evidence to support use |

| 19 | United Kingdom | Recommended for use only if acetaminophen not effective |

| 3 | Europe | Recommended for short-term use (up to 3 months) |

| 20 | Italy | Evidence to support its use |

| 21 | United States | Moderate evidence to support use |

| COX-2 Inhibitors | ||

| 19 | United Kingdom | Recommended for use only if acetaminophen not effective |

| Aspirin | ||

| 18 | Belgium | No evidence to support use |

| 21 | United States | Insufficient evidence to estimate efficacy |

Simple Analgesics

The CPG from the United Kingdom in 2009 recommended acetaminophen as the first choice medication for the management of CLBP.19

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found insufficient evidence to support the use of acetaminophen for CLBP.18

The CPG from Italy in 2007 found evidence to support the efficacy of acetaminophen with respect to improvements in pain.20 That CPG also recommended acetaminophen as the first choice medication for the management of CLBP.

The CPG from the United States in 2007 found moderate-quality evidence to support the efficacy of acetaminophen with respect to improvements in pain.21

Findings from the aforementioned CPGs are summarized in Table 11-2.

TABLE 11-2 Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations on Simple Analgesics for Chronic Low Back Pain

| Intervention | Country | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | ||

| 19 | United Kingdom | Recommended |

| 18 | Belgium | Insufficient evidence to support use |

| 20 | Italy | Recommended |

| 21 | United States | Moderate evidence to support use |

Muscle Relaxants

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found very low-quality evidence to support the efficacy of muscle relaxants for the management of CLBP and low-quality evidence to support the efficacy of benzodiazepine muscle relaxants for the management of CLBP.18 That CPG also found no evidence to support the efficacy of diazepam for the management of CLBP and concluded that tetrazepam is effective with respect to short-term improvements in pain. There was conflicting evidence to support the use of nonbenzodiazepine muscle relaxants for CLBP.18

The CPG from Europe in 2004 found limited evidence that muscle relaxants are not effective for the relief of muscle spasm.3 That CPG concluded that muscle relaxants should be considered as one management option for short-term pain relief in patients with CLBP.3 There was strong evidence to support the efficacy of benzodiazepine muscle relaxants in the pain relief of patients with CLBP and conflicting evidence to support the efficacy of nonbenzodiazepine muscle relaxants for CLBP.3

The CPG from Italy in 2007 found evidence to support the efficacy of muscle relaxants with respect to improvements in pain.20 That CPG concluded that muscle relaxants are an option for the management of CLBP, but should not be used as a first choice medication.

The CPG from the United States in 2007 found insufficient evidence to support the efficacy of muscle relaxants for CLBP.21 Nevertheless, that CPG concluded that muscle relaxants are one possible option for the management of CLBP. There was also evidence to support a moderate benefit for benzodiazepine muscle relaxants for CLBP.21

Findings from the above CPGs are summarized in Table 11-3.

TABLE 11-3 Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations on Muscle Relaxants for Chronic Low Back Pain

| Intervention | Country | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Muscle Relaxants | ||

| 18 | Belgium | Low-quality evidence to support use |

| 3 | Europe | May be considered for short-term use |

| 20 | Italy | May be considered but not as first choice |

| 21 | United States | Are an option for management of CLBP |

| Benzodiazepines | ||

| 18 | Belgium | Low-quality evidence to support efficacy |

| 3 | Europe | Strong evidence of efficacy |

| 21 | United States | Evidence to support moderate benefit |

| Diazepam | ||

| 18 | Belgium | No evidence to support efficacy |

| Tetrazepam | ||

| 18 | Belgium | May be considered for short-term use |

| Non-Benzodiazepines | ||

| 18 | Belgium | Conflicting evidence supporting use |

| 3 | Europe | Conflicting evidence supporting efficacy |

CLBP, chronic low back pain.

Systematic Reviews

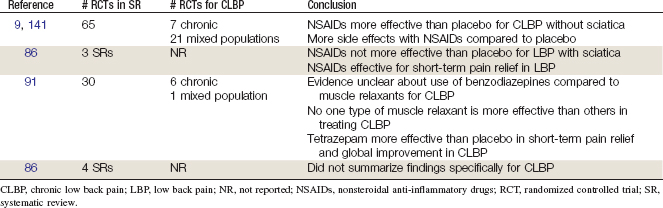

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Cochrane Collaboration

An SR was conducted in 2008 by the Cochrane Collaboration on NSAIDs for LBP.9 A total of 65 RCTs were included. Of these studies, 37 included patients with acute or subacute LBP, 7 included patients with CLBP, and 21 included mixed duration LBP populations.22–85 Meta-analysis showed that NSAIDs were more effective than placebo for acute and chronic LBP without sciatica, but also showed that there were more side effects with NSAID use compared with placebo. This review concluded that NSAIDs provide short-term improvement in pain among patients with acute and chronic LBP without neurologic involvement. The SR also concluded that the different types of NSAIDs are equally effective and that COX-2 inhibitors may exhibit fewer side effects than older NSAIDs, yet recent studies show that COX-2 inhibitors are associated with increased cardiovascular events among certain patients.

American Pain Society and American College of Physicians

An SR was conducted in 2007 by the American Pain Society and the American College of Physicians CPG committee on medication for acute and chronic LBP.86 That review identified three SRs on NSAIDs (including the Cochrane Collaboration review mentioned earlier).9,87,88 The second SR evaluated in this review also reached similar conclusions as the Cochrane review.9,87. The third SR concluded that NSAIDs were not more effective than placebo for LBP with sciatica.88 Overall, this review concluded that there is good evidence that NSAIDs are effective for short-term pain relief in LBP, and there is little evidence suggesting differences in efficacy between various NSAIDs. However, this review also concluded that there is a paucity of data on serious adverse events related to NSAID use in LBP, which is an important consideration given previous concerns over gastrointestinal (GI) and cardiovascular safety. There were two additional RCTs on CLBP identified in these SRs.89,90

Findings from the above SRs are summarized in Table 11-4.

Muscle Relaxants

Cochrane Collaboration

An SR was conducted in 2003 by the Cochrane Collaboration on muscle relaxants for nonspecific LBP.91 A total of 30 RCTs were included, of which 77% were found to be of high quality. Of these studies, 23 included patients with acute LBP, 6 included patients with CLBP, and 1 study included mixed duration LBP populations.27,28,49,55,92–117 The review concluded that there is strong evidence that nonbenzodiazepine muscle relaxants were more effective than placebo in short-term pain relief and overall improvement in acute LBP patients. However, they were associated with significantly more overall adverse events and CNS adverse events than placebo; no differences were found in GI adverse events. The evidence was less clear for the use of benzodiazepines compared with placebo for acute LBP, and muscle relaxants (both benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepines) for CLBP. Although pooled analysis of two studies found tetrazepam to be more effective than placebo in short-term pain relief and global improvement in CLBP, the review did not find that one type of muscle relaxant was more effective than any other.

American Pain Society and American College of Physicians

An SR was conducted in 2007 by the American Pain Society and American College of Physicians CPG committee on medication for acute and chronic LBP.86 That review identified four SRs on muscle relaxants, including the Cochrane Collaboration review mentioned earlier.87,88,91,118 Two additional trials not included in the Cochrane review and identified in two additional SRs, also included patients with CLBP.119,120 Two other SRs reached similar conclusions as the Cochrane review, while a third SR that focused on sciatica88 found no difference between tizanidine and placebo based on one higher-quality trial.87,88,91,118 Overall, the SR concluded that there is good evidence that muscle relaxants are effective for short-term pain relief in acute LBP. There is little evidence that there are differences in efficacy between various muscle relaxants. Little evidence was found on the efficacy of the antispasticity medications baclofen and dantrolene for LBP. The review also noted that muscle relaxants are associated with more CNS adverse events than placebo.

Randomized Controlled Trials

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Eleven RCTs and 12 reports related to those studies were identified.38,59,60,62-64,73,83,121-124 Their methods are summarized in Table 11-5. Their results are briefly described here.

TABLE 11-5 Randomized Controlled Trials of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs for Chronic Low Back Pain

An RCT conducted by Hickey and colleagues38 included CLBP patients without neurologic involvement, who had symptoms lasting longer than 6 months. Participants were randomized to either diflunisal (500 mg twice daily) for 4 weeks or paracetamol (1000 mg four times daily) for 4 weeks. At the end of 4 weeks, there was improved pain (0-3 scale) and disability (0-3 scale) in patients from both groups compared with baseline (P values not reported). More patients in the diflunisal group had improved pain and disability than in the paracetamol group (P values not reported). This study was considered of higher quality.

An RCT with a crossover design was conducted by Berry and colleagues59 on CLBP patients with or without neurologic involvement, who had symptoms for at least 3 months. Participants were each given (1) naproxen (550 mg twice daily), (2) diflunisal twice (550 mg twice daily), or (3) placebo in random sequence, with each treatment lasting for 2 weeks. At the end of the treatment period, there was a significant reduction in pain (visual analog scale [VAS]) in the naproxen group, a significant increase in pain in the placebo group, and no significant change in the diflunisal group. There was a significant difference in pain between the naproxen group and the diflunisal and placebo groups. Disability was not measured in this study. This study was considered of lower quality.

An RCT conducted by Postacchini and colleagues83 included acute and chronic LBP patients with or without radiating pain. Participants were randomized to (1) diclofenac (10 to 14 days for acute cases, 15 to 20 days for chronic cases; the dose was reported as “full dosage” without providing any further details); (2) chiropractic manipulation; (3) physical therapy; (4) bed rest; (5) back school; or (6) placebo. At the end of 6 months, there was improvement in the mean combined score for pain, disability, and spinal mobility in all groups (P

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree