CHAPTER 21 Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Description

Terminology and Subtypes

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a psychosocial intervention approach in which behavioral change is initiated by a therapist helping patients to confront and modify the irrational thoughts and beliefs that are most likely at the root of their maladaptive behaviors. Maladaptive behaviors are those that prevent an individual from adjusting appropriately to normal situations, and which are considered counterproductive or not socially acceptable (Figure 21-1).1 The primary goal of CBT is to identify these maladaptive behaviors, recognize beliefs associated with those behaviors, correct any inappropriate beliefs, and replace those beliefs with more appropriate ones that will result in greater coping skills and adaptive behaviors (Figure 21-2).

There are several approaches to CBT and various ways of incorporating CBT into the management of chronic low back pain (CLBP). CBT alone does not address all of the contributing factors to CLBP (e.g., anatomic, biologic, physiologic), and it is not intended to replace interventions aimed at correcting those factors when appropriate. The focus of CBT in the context of CLBP is mainly to address psychological comorbidities that may impede recovery. If those factors are solely responsible for CLBP, then CBT may be appropriate as the main intervention. However, patients sometimes find it difficult to perceive the utility of CBT as the sole treatment for CLBP.2 Use of the term CBT varies widely and may be used to denote self-instructions (e.g., distraction, imagery, motivational self-talk), relaxation, biofeedback, development of adaptive coping strategies (e.g., minimizing negative or self-defeating thoughts), changing maladaptive beliefs about pain, and goal setting (Figure 21-3).3 Patients referred for CBT may be exposed to varying selections of these strategies that are specifically tailored to their needs.

History and Frequency of Use

CBT was pioneered by Aaron Beck and bears some similarities to the rational emotive behavioral therapy developed earlier by Albert Ellis.4 Beck proposed that people often have two levels of thought that occur simultaneously: (1) automatic thoughts, which are generally evaluative; and (2) maladaptive thoughts, which CBT seeks to challenge and reframe. Many authors trace the origins of CBT farther back in time to Freud’s extensive exploration of the unconscious mind, which resembles the CBT concept of “automatic thoughts” and consists of occasional irrational thoughts over which the patient has no control.5,6

Regardless of this common genesis, there are important differences between the application of CBT and Freudian psychoanalysis. Whereas Freud focused on the past to discover the root of a patient’s psychopathology, CBT focuses on resolving maladaptive behavior in the present without dwelling on its origin.5 Additionally, whereas Freudian psychoanalysis often requires a lengthy course of treatment during which progressively deeper insight is sought, CBT is widely viewed as a “quick” behavioral therapy intended to achieve long-term results in fewer than 20 sessions.5

Others who have contributed to the development of CBT include the American psychologists Albert Bandura and Donald Meichenbaum, who described pain behavior in terms of the learning theories of classic conditioning and operant conditioning.6,7 For example, classic conditioning may be at play when visiting a doctor’s office (e.g., a place where the patient has experienced or focused on their pain in the past) induces tension or fear, thereby increasing the painful experience.7 Operant conditioning may be occurring when “sick” behavior (e.g., complaining about LBP and decreasing activities) is rewarded by a patient’s family (e.g., patient receives care or increased attention), workplace (e.g., patient placed on almost fully paid sick leave or given modified duties), or physician (e.g., patient receives more attention during a visit if symptoms appear severe). Each of these societal responses to the patient’s behaviors may reinforce the patient’s perceived worth and prevent them from managing their pain or improving their function.7

Procedure

Turk and Flor8 describe CBT as having six distinct phases: (1) assessment, (2) reconceptualization, (3) skills acquisition, (4) skills consolidation and application training, (5) generalization and maintenance, and (6) post-treatment assessment and follow-up. The assessment phase involves a conversation with patients and their families, and a series of self-reported measures that can be used by the practitioner to identify the degree of psychosocial impairment and determine the most appropriate course of action. The reconceptualization phase makes up much of the “cognitive” portion of CBT. A great deal of the psychopathology associated with chronic pain conditions is thought to originate in the automatic thoughts or irrational beliefs that patients with pain may have regarding their pain condition, including thoughts such as “I am never going to get better,” “I cannot bear this much pain,” “I am a failure in life because I am in pain,” and other maladaptive cognitions. The reconceptualization phase of CBT seeks to help patients challenge and question the rationality of such maladaptive thoughts.

Gatchel and Robinson9 provided a comprehensive overview of CBT for managing chronic pain, including CLBP, with a session-by-session guide to a typical CBT intervention for a patient with chronic pain. Their approach consists of a short-term, skills-oriented therapy in which new skills are taught at each session to (1) correct negative (distorted) thinking about chronic pain, (2) control emotional reactions to chronic pain, and (3) cope more effectively with chronic pain and other stressors.

Theory

Mechanism of Action

CBT itself does not attempt to directly address the anatomic or physiologic components of CLBP. Rather, CBT attempts to improve how symptoms of CLBP may be perceived and what impact they may have on a patient’s life. By reframing maladaptive thoughts and coping strategies, CBT can decrease distress and promote appropriate self-care, which may in turn reduce the pain experience.7 CBT interventions must be tailored to each patient because they are intended to address an individual’s interpretation, evaluation, and beliefs about his or her health condition and coping repertoire. The exact mechanism of action for CBT may then depend to some degree on the specific behaviors and beliefs it must correct. By improving maladaptive behaviors with respect to CLBP, CBT may affect the degree of emotional and physical disability associated with that condition, if not the underlying symptoms themselves.10

The general CBT procedure described earlier by Turk and Flor8 is used for most psychopathologies encountered, including those that may be active in CLBP. However, there are distinctions in the application of this technique that are specific to the patient’s diagnosis. Therefore, when discussing the mechanism of action for CBT, one needs to take into account some of the more prevalent psychosocial diagnoses seen in patients with CLBP. For example, patients with CLBP may experience anxiety associated with activities that may cause pain or increase existing pain. As described in the “medical-symptom stress cycle,” such anxiety can lead to behavioral changes that exacerbate the pain.11 To treat such anxiety, the therapist can use a variety of techniques, including biofeedback and relaxation training. The goal of these techniques is to reduce the anxiety associated with the pain experience and to help ease the patient’s tension, thereby decreasing some of the pain symptoms.

Indication

Although most patients with CLBP could be diagnosed with a pain disorder, it has also been found that they also have a significantly higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders than the general population.12 Indeed, spine clinicians must often deal with comorbidities such as the psychiatric sequelae of CLBP. To treat patients with CLBP using CBT, it is often necessary to treat comorbid psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, mood disorders, pain disorders, or depression. However, even though an association between CLBP and certain psychiatric disorders has been noted, this does not indicate a causal relationship. In the absence of a carefully experimentally controlled longitudinal study, no such causal order can be discerned. Clinicians should not assume that comorbid psychiatric disorders were present before developing CLBP.

In fact, development of severe or prolonged CLBP could potentially lead to the development of subsequent psychiatric disorders. For example, persons suffering from a chronic pain disorder may develop alcohol, drug, or medication dependence or addiction in an attempt to obtain some relief.13 Additionally, withdrawal from regular activities such as work, school, and leisure pursuits due to pain may lead to depression or other affective disorders, and has been shown to be substantially more prevalent in those who suffer from chronic pain.12,13 Patients suffering from CLBP are also known to suffer from pain-related, rather than generalized, anxiety.14 The ideal patient with CLBP for CBT is one with average intelligence, who is motivated to learn coping skills to help manage his or her pain, is compliant with the treatment protocol, and is willing to complete “homework” exercises between treatment sessions.

Assessment

Before receiving CBT, patients should first be assessed for CLBP using an evidence-based and goal-oriented approach focused on the patient history and neurologic examination (if necessary), as discussed in Chapter 3. Additional diagnostic imaging or specific diagnostic testing is generally not required before initiating this intervention for CLBP. Certain questionnaires (e.g., Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia) may be helpful to identify subsets of patients with CLBP who may benefit from specific interventions aimed at addressing those issues (e.g., fear avoidance training, as discussed in Chapter 7).

Efficacy

Clinical Practice Guidelines

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found high-quality evidence that CBT is more effective than no treatment in patients with CLBP.15 The same CPG also found moderate evidence to support the efficacy of CBT in the management of CLBP, and no difference in the efficacy of various forms of behavioral interventions for CLBP. That CPG concluded that CBT can be recommended as one management option for CLBP.

The CPG from Europe in 2004 found strong evidence that CBT is more effective than placebo or no treatment with respect to improvements in pain, function, and mental health in patients with CLBP.16 That CPG also found strong evidence that there is no difference in the efficacy of various forms of behavioral interventions for CLBP. There was limited evidence overall to support the efficacy of CBT in the management of CLBP.

The CPG from the United Kingdom in 2009 found limited evidence to support the efficacy of CBT or other behavioral interventions as sole therapies for the management of CLBP.17 The same CPG also found no evidence to support the efficacy of longer-term CBT or other behavioral interventions unless they are combined with physical therapy. The CPG recommended CBT or other behavioral interventions as one management option for CLBP, but only when combined with other approaches.

The CPG from the United States in 2007 found moderate-quality evidence to support a moderate benefit for CBT in patients who do not obtain adequate relief with self-care alone.18

Findings from these CPGs are summarized in Table 21-1.

TABLE 21-1 Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Low Back Pain

| Reference | Country | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| 15 | Belgium | Recommended |

| 16 | Europe | Evidence of efficacy |

| 17 | United Kingdom | Recommended, but only when combined with other approaches |

| 18 | United States | Moderate-quality evidence to support moderate benefit |

Systematic Reviews

Cochrane Collaboration

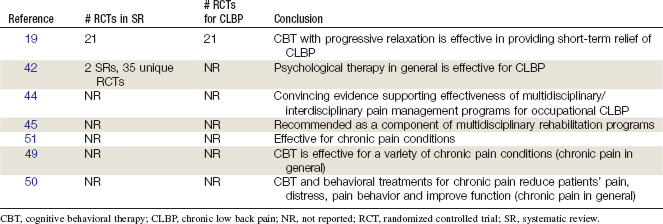

An SR was conducted in 2003 by the Cochrane Collaboration on CBT for nonspecific CLBP.19 A total of 21 RCTs were included.20–40 Two RCTs found that progressive relaxation led to greater improvements in pain, functional, and behavioral outcomes than in control subjects.32,33 Seven RCTs examining electromyographic biofeedback found conflicting results and RCTs examining operant therapy versus control found no differences for behavioral or functional outcomes.23,27,30,32,34,36,40 Combined respondent cognitive therapy showed statistically significant improvement in pain outcomes, however, no differences were found for behavior and functional outcomes.27,33,34,41 Behavioral therapy was more effective than usual care in one RCT, but was not as effective as exercise in another.25,40 This review concluded that CBT combined with progressive relaxation is effective in providing short-term relief for CLBP.19 This SR also concluded that CBT produced the same effects as exercise therapy and that the long-term effects of CBT are unknown.

American Pain Society and American College of Physicians

An SR was conducted in 2006 by the American Pain Society and American College of Physicians CPG committee on nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic LBP.42 That review identified two SRs related to CBT, including the Cochrane Collaboration review mentioned earlier.19,43 The other review identified had conclusions consistent with those of the Cochrane review: CBT is effective in the short term for CLBP.43 These SRs included a total of 35 unique RCTs (references were not provided). No additional trials have been identified. RCTs included in the non-Cochrane review indicated that psychotherapy may not improve outcomes when added to other noninvasive therapies.43 This SR concluded that psychological therapy is effective for chronic or subacute LBP.42

Other

In an earlier review, Gatchel and Bruga concluded that there is now convincing evidence-based data demonstrating the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of multidisciplinary pain management programs for occupational CLBP.44 Similar findings were reported in the Cochrane Collaboration on multidisciplinary treatment approaches to CLBP, some of which include CBT itself, or at least some of its philosophies.45

Multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs are often based on the biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain, which views chronic pain conditions—including CLBP—as complex illnesses requiring consideration of potential complex interactions between biological and psychosocial variables.46–48 As such, it follows from this perspective that appropriate treatment requires a comprehensive approach designed to address all such factors that cause, mediate, and perpetuate chronic pain and disability.

An influential early review by Morley and colleagues49 reported the results of their SR and meta-analysis of the existing RCTs of the efficacy of CBT and behavioral therapy for chronic pain in general. Their findings concluded that such treatment is effective for a variety of chronic pain conditions in producing improvement in the following important areas: (1) pain experience; (2) pain behavior and activity level; (3) cognitive coping and appraisal; and (4) social functioning.

Subsequently, another review reported numerous controlled clinical trials of CBT and behavioral treatment for chronic pain in general, alone or more commonly in multidisciplinary intervention contexts, that indicated these treatments to be efficacious.50 Results of many published studies in the scientific literature showed that, overall, CBT and behavioral treatments for chronic pain reduced patients’ pain, distress, and pain behavior, and improved daily functioning.

More recently, a review on CBT interventions for chronic pain concluded that “cognitive-behavioral treatment interventions for chronic pain have expanded considerably. It is now well established that these interventions are effective in reducing the enormous suffering that patients with chronic pain have to bear. In addition, these interventions have potential economic benefits in that they appear to be cost effective as well.”51

Findings from these SRs are summarized in Table 21-2.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree