Key Clinical Questions

What strategies may improve emergency department (ED) throughput and minimize ED crowding?

How can hospitalists and Emergency Medicine (EM) physicians collaborate to improve the care of patients boarded in the ED?

How can hospitalists and EM physicians improve the quality and safety of hand-offs between their departments?

What basic principles underlie the operation of an observation unit?

Introduction

Co-management of patients in the emergency department (ED) by Emergency Physicians and Hospital Medicine physicians has become necessary to alleviate ED crowding and optimize care of patients boarded in the ED while awaiting an inpatient bed. This chapter describes the challenge of ED crowding and how co-management strategies can improve patient flow from the ED into the hospital and improve the safety of patients who must be boarded. The chapter also examines two additional strategies for decreasing ED crowding: establishing a process for the triage of patients to appropriate services and locations within the hospital, and using ED based observation units.

The Institute of Medicine in its 2006 report entitled Hospital-Based Emergency Care: At the Breaking Point1 concluded that EDs in the United States are in crisis, with hospital crowding being the single largest contributor to long wait times and adverse clinical outcomes. Investigators have found an association between ED crowding and a higher risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with an initial diagnosis of chest pain. Others have found that, for patients with non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, long ED stays are associated with decreased adherence to clinical guidelines and an increased incidence of repeat myocardial infarction. An estimated 91% of the nation’s EDs are overcrowded at any given time.

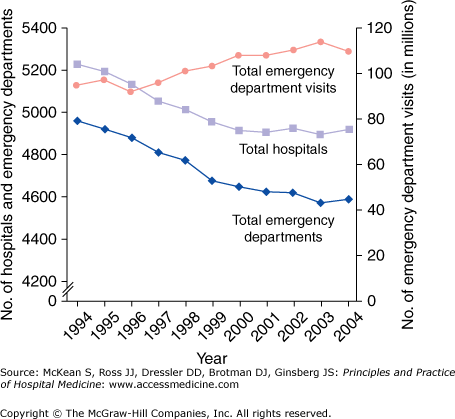

The causes of ED crowding are myriad and include increased utilization, demographic changes (most significantly the aging of the population), shortages of particular types of health care providers, and changing financial trends. Most significant amongst these were increased utilization and insufficient numbers of inpatient hospital beds. From 1996 to 2006 ED visits increased 32%, from 90.3 million to 119.2 million, equating to 325,000 visits per day. During that same time the number of ED visits per 100 persons rose 18%, from 34.2 to 40.5. In 2005 approximately one-fifth of the U.S. population had visited an ED within the previous 12 months. Ironically, the increase in ED utilization has been concurrent with a decrease in the total number of EDs. From 1996 to 2006 the number of EDs in the United States declined 4.6%, from 4019 to 3833 (Figure 123-1).

Figure 123-1.

Trends in emergency department utilization, number of hospitals, and number of emergency departments in the United States, 1994–2004. (Reproduced, with permission, from Kellermann AL. Crisis in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(13): 1300–1303. Copyright © 2006 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.)

Although increased utilization and constrained inpatient capacity are the predominant causes of ED crowding, demographic changes have also pressured ED capacity. The uninsured and the elderly, two groups of patients who tend to present with a high degree of acuity, are an increasing proportion of the patients treated in EDs. In 2006 uninsured patients accounted for 17.4% of all ED visits. In the same year patients over 75 years old were the age group with the highest per capita visit rate.

Shortages of several types of health care providers have further exacerbated the problem of ED crowding. The shortage of hospital-based nurses, estimated in July 2007 at 116,000, has left many EDs struggling to find full staffing. The well-publicized shortage of primary care physicians has left many patients with no choice but to use EDs for the initial evaluation of their medical condition, regardless of acuity. Less well publicized than nursing and primary care physician shortages is the shortage of surgeons and medical subspecialists willing to be available for calls and provide consultative or admitting services to the ED. Such physicians typically cite poor compensation and the threat of increased legal liability among their reasons for avoiding covering the ED.

Staffing models have not completely accommodated the needs of EDs, now the primary portal of entry into the hospital. Most hospitals are staffed around a traditional 8 am –5 pm, Monday through Friday model, with lower staffing during other times. Yet in 2006, 62.9% of ED visits occur outside of these hours with peak ED occupancy occurring at 7 pm. Scheduling of elective surgeries has also not evolved to accommodate ED needs. Most elective surgeries are front loaded during the week so that ancillary services such as physical and occupational therapy are available in the immediate postoperative period. This constrains operating room capacity on precisely the days that are busiest for EDs.

|

Shortages of inpatient hospital beds have paralleled those seen in EDs; high hospital census conditions limit patient flow out of the ED and hence further exacerbate ED crowding. The most frequent shortage of inpatient beds occurs in the nation’s intensive care units (ICUs). One of the most frequent causes of delays in getting patients admitted from the ED is lack of ICU capacity. Across the country ICU occupancy rates at any given time are extraordinarily high, between 84% and 93% in various studies, and demand for ICU beds continues to increase. Lack of inpatient beds leads to “boarding” of admitted patients in the ED, which further restricts already constrained capacity and adversely effects clinical outcomes. The Institute of Medicine has challenged hospitals, and by extension hospitalists, to improve the flow of patients through the ED in order to eliminate ED boarding completely. Boarding and crowding have several negative consequences, including impaired flow of patients through the ED, decreased patient and provider satisfaction, poor clinical outcomes, and ambulance diversion to other less crowded EDs.

Predictably, flow of patients through the ED decreases as patient volume approaches and exceeds capacity. Under such conditions wait times for initial evaluation by a health care provider increase and the overall ED length of stay (ED LOS) increases. Although there has been significant attention to this problem over the last few years, a 2009 report by the General Accounting Office (GAO) entitled Hospital Emergency Departments: Crowding Continues to Occur and Some Patients Wait Longer than Recommended Time Frames illustrates that ED crowding continues as a significant issue. In 2006 patients needing immediate care waited an average of 28 minutes while those needing emergent care waited an average of 37 minutes, both exceeding time frames recommended by the National Center for Health Statistics (Table 123-1). In the same year the average ED LOS was 199 minutes, an increase of 12% from 178 minutes in 2001.

Patient Acuity Level & Recommended Time Frame | Average Wait Time in Minutes | Percentage of Visits in which Wait Time Exceeded Recommended Time Frames |

|---|---|---|

Immediate (less than 1 minute) | 28 | 74 |

Emergent (1 to 14 minutes) | 37 | 50 |

Urgent (15 to 60 minutes) | 50 | 21 |

Semiurgent (greater than 1 to 2 hours) | 68 | 13 |

Nonurgent (greater than 2 to 24 hours) | 76 | N/A |

ED crowding also impacts overall hospital outcomes, including increased LOS and adverse events. A large, multicenter, cross-sectional study demonstrated that patients admitted to the ICU with a greater than six-hour delay in transfer from the ED had a significantly longer hospital length of stay and higher in-hospital mortality. In a second study increased ED LOS beyond eight hours added approximately 24 hours of total time in the hospital. Other studies have shown that patients boarded in the ED during times of crowding experience an increased number of adverse events.

EDs often resort to “diversion,” the practice of alerting local emergency medical services (EMSs) that they can no longer accept patients. Several studies demonstrate that patient diversion is associated with increased mortality. Diversion also costs individual hospitals approximately $1086 per hour in lost revenue. A recent study estimates that, on average, an ambulance is diverted once every minute in the United States, roughly half a million times per year.

|

Various regulatory and professional pressures on EM physicians may affect their clinical practice and also contribute to ED crowding, affecting patient flow within hospitals. Regulatory pressures include the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA). EMTALA requires EDs, EM physicians, and on-call physicians covering EDs to provide a screening examination to any individual who presents to an ED and requests examination or treatment. A patient found to have an emergent condition must be treated until stabilized or transferred to another facility to receive treatment. According to EMTALA an emergency medical condition means a medical condition manifesting itself by acute symptoms of sufficient severity (including severe pain) such that the absence of immediate medical attention could reasonably be expected to result in placing the health of the individual (or, with respect to a pregnant woman, the health of the woman or her unborn child) in serious jeopardy, serious impairment to bodily functions, or serious dysfunction of any bodily organ or part.

Professional pressures affecting ED physicians include professional organization expectations, public expectations, and legal risks. The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Emergency Medicine Physician Performance Measure Set holds EM physicians accountable to consensus guidelines for a number of disease states. They address quality measures, such as aspirin on arrival for acute myocardial infarction, electrocardiogram (ECG) for syncope, and oxygen saturation (SpO2) evaluation and empiric antibiotics for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). The Prudent Layperson Standard (advocated by ACEP) suggests that health care coverage in EDs should be based not on diagnosis but on symptoms since the public cannot be expected to self-diagnose. High legal liability occurs in the United States compared with other English-speaking nations. Compared with the United Kingdom and Australia, the United States has 50% more medical liability claims and 350% more than Canada. Unlike Australia the United States lacks federal policies that protect physicians from litigation, even for those patients covered under EMTALA.

Improving Patient Flow through the Emergency Department

In order to identify strategies for minimizing ED crowding patient flow can be categorized into three stages: input, throughput, and output (Table 123-2). Hospitalists should lead collaborative efforts to improve flow through the ED and can impact various aspects of the input-throughput-output model. Since they are increasingly tasked with admitting from outpatient clinics, hospitalists can diminish ED input by selecting appropriate patients for direct admission, bypassing the ED entirely. When asked to admit from the ED, hospitalists can improve throughput by assisting EM physicians with selection of specific diagnostic tests needed to determine disposition and with triage to the most appropriate level of care. Even when they are not asked to admit, hospitalists can offer their services as consultants to assist EM physicians in developing a care plan, including initiating directed treatment or specifying optimal follow-up for patients who may not require admission. At the output stage hospitalists can standardize and streamline their admission processes and policies. They should be well versed with national as well as institution-specific admission guidelines. Hospitalist and EM leaders should partner to provide ongoing education for physicians within their departments regarding accepted guidelines and clinical care practices.

Input | Throughput | Output |

|---|---|---|

Clinic referrals Ambulance drop-offs Walk-ins Help lines | Triage Immediate assessment Stabilization Lab turnaround Radiology turnaround Reassessment Development of treatrment plan Response time of consultants | Admission procedures Signout to admitting service Referals to outpatient clinics Transfer to another facility LWBS AMA Death |